San Francisco Opera is continuing their Fall Season with an extraordinary showing of Richard Wagner’s masterpiece Lohengrin, that opened on Sunday October 15 at the beginning of multi-year journey into Wagner’s (and Verdi’s) operas with Music Director Eun Sun Kim in a contemporary production by renowned director David Alden. The last time the Swan Knight made appearance in the War Memorial stage was in 2012, where then-Music Director Nicola Luisotti conducted a staging by Daniel Slater with Brandon Jovanovich in the title role.

San Francisco Opera couldn’t have predicted the current state of affairs in engaging this co-production (set in a war-torn European city) with the Royal Opera House and Opera Vlaanderen that first premiered in London in 2018 under a very different climate. On Sunday, General Director Matthew Shilvock prefaced the show with a heartfelt acknowledgement that we lived in a very difficult time in the world given the conflict in Israel and Gaza and the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, and that the militaristic emphasis of the production might prove to be difficult for some in the audience.

In his blog “Backstage with Matthew,” Shilvock detailed Alden’s creative process in creating Lohengrin, writing:

“For David, while Lohengrin is a tale of wish fulfillment—a knight in shining armor rescuing a damsel in distress, it has a much darker, political overtone to it. Wagner wrote the opera in the mid-19th Century at the height of political fervor around the unification of the German city-states. Wagner himself was exiled to Switzerland after his own political activism. […] The political element is very important in David’s interpretation of the piece. David wanted to bring it into a more modern context—a world in the midst of war, bombed, shaken-up, being militarized. A world in which the population is at once in need of rescue, but is also being pulled into the insidious evil of darkness, represented by the iconography of fascism. And even a person who comes into this world from a place of light, goodness, and even holiness (a Knight of the Holy Grail), still risks becoming dragged into the ugliness of war.”

That “world” was realized efficiently by set designer Paul Steinberg simply by using two movable towering blocks of distorted buildings, which served as both the backdrops as well as spaces for the chorus members, with the opera pretty much playing out at the junction between these walls. When the curtain opened (both Preludes were played to closed curtains), the audience was thrown straight into chaos with chorus members frantically moving around under police’s orders with guns visible. Gideon Davey’s everyday cloth costumes and Simon Bennison’s dark lighting further accentuate that disorderly state. The location also seemed to suggest that this Brabant was a close-knit community (a homage to Anatevka from Fiddler on the Roof, maybe?) on the verge of significant change with the arrivals of King Heinrich and, particularly, Lohengrin.

While all those did quickly establish the Brabant of Alden’s vision, closer to home the hyper-realistic settings inadvertently gave way to a sense of unease and trepidation, particularly with regards to all things happening here in the last couple of years. It could simply be San Francisco during all those protests! From there, Alden’s interpretations turned into much more than what he envisioned – at least to this reviewer – as there was a duality of interpretations running almost concurrently: a reflection of the world at war and a commentary on the society that we live in, making the staging visually engaging and extremely thought-provoking!

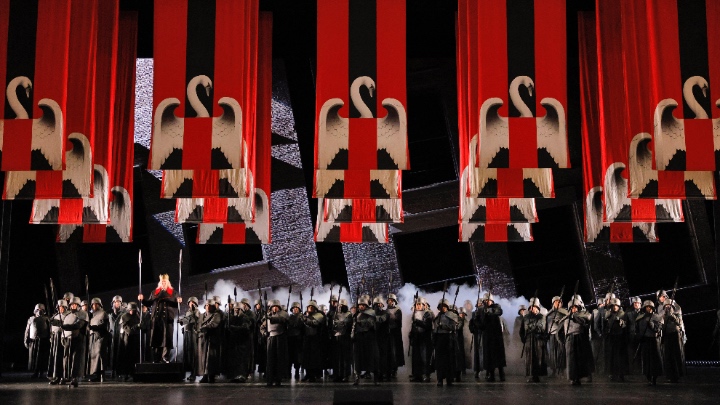

The staging reached its fever pitch during Act 2, where a gigantic swan statue adorned the stage and the ceiling was disturbingly plastered with red white and black flags bearing the swan logos during the wedding scene. Here Alden smartly instilled ambiguity, not just to Elsa but also to the audience, about the identity of the stranger and whether his intention was pure. (Remember, power corrupts, folks!) The love, so pure and true at the end of the first act, had shifted by the time Lohengrin and Elsa entered in the cathedral at the end of Act 2.

The heavy emphasis on the political aspect might make the romantic side of the story felt a little bit skimpy at times. The famous “Bridal Chorus,” for example, arrived without any fanfare (it didn’t help that it was played very fast) and left as quickly, almost like an afterthought (It probably made sense to have a quick wedding in a troubled town!). Only during the first scene of Act III (The Bridal chamber scene) that Alden and Steinberg decided to eschew the uniformly dark settings to show the most jarring moment in the whole opera, a completely white and bright room with all-white bed and adorned with a giant replica of August von Heckel’s The Arrival of Lohengrin in Antwerp mural (the original is in Neuschwanstein Castle), before Telramund tore the white wall to attack Lohengrin and we were back into dark Brabant. Notwithstanding, it didn’t mean that Alden didn’t pay attention to those tender moments; Lohengrin’s utterance of “Elsa, ich liebe dich!” in Act I amid the chaos felt so pure and precious that I shed a tear.

By the time the final scene came, with that “iconography of fascism” crowding the space and Lohengrin himself turning his back on Elsa, a cloud of doubt and confusion permeated the air, and the audience couldn’t help but question who the “good guys” really were. I believe this was what Alden intended all along, to bring out the message that there was only thin line between love and hate, or between right and wrong, and that in war there was no winner. Lohengrin’s surprisingly cold treatment of Elsa’s plight almost seemed to imply that his departure might not have been caused (only) by Elsa’s betrayal of trust, but also by his refusal to be used as a machine of war. Seen in that context, the appearance of Duke Godfrey as a child dispensed a deep sense of hope and renewal, elevating the staging and bringing it to an exuberant conclusion.

On Sunday, the musical portion of the show was on a whole different level altogether. Kim, who conducted her first Lohengrin with this performance, led the Orchestra in a reading marked with clarity, power, majesty and splendor. In her hand, Wagner’s score – the last of his Romantic period – came alive with the emphasis on the many musical motifs (precursor to the future leitmotif principles in the Ring cycle). I was particularly taken aback by the beauty and cohesion of the onstage/backstage 4 herald trumpets (played by Joseph Brown, David Burkhart, David Costelloand John Freeman), who gorgeously signaled The King’s Herald in unison. (Interestingly, Alden staged many of those occasions as a kind of civil defense siren blaring the tunes with the 4 trumpeters hidden nearby.)

Kim chose a well-judged pace that maintained the arc of the whole score (maybe except the aforementioned “Bridal Chorus”), an important achievement as Lohengrin could easily sound plodding and tiresome without tight control (bear in mind that Lohengrin marked Wagner’s transition into the through-composed verses that were the hallmark of his later operas). Climaxes were thrillingly shaped, and the quiet parts were incisively rendered. Kim was also sensitive to the needs of her cast, making sure that each exceled without drowning them with the sound of the orchestra. The SF Opera Chorus, led by John Keene, had never sounded better, as they sang (and moved) with power and conviction as the residents of Brabant and made an essential contribution to the overall success of the show.

What a glorious cast that SF Opera assembled for this Lohengrin; not only did they maintain great rapport amongst each other, but they were fully committed to Alden’s interpretation and performed the roles with aplomb. It was even more surprising to learn that most of the cast were either making role debuts, or, in the case of one member, an American debut!

New Zealander heldentenor Simon O’Neill was a veteran of the title role, having debuted the role in 2009 at Covent Garden, followed by Bayreuth debut (in the same role) the following year. On Sunday O’Neill brought decades of experience into his powerful and moving portrayal of the Swan Knight. There was some reedy quality in his voice that might take a while to get used to, but nevertheless, his musicality shone through and he had no troubles sailing over the orchestra and chorus. What fascinated me most was the arc in his personification of the role; his was decidedly fully human, moving from being fully in love to indifferent to even fear (of the outcome) … all were fleshed out with his voice and body language, somewhat different take than the usual role that maintained the otherworldly aura of the character.

As Elsa, soprano Julie Adams (a 2015/16 Adler Fellow) more than held her own with her gleaming bright voice that sounded alternatingly both powerful and fragile as needed by the score. Alden assigned a highly physical role to Elsa in this staging, and Adams performed them confidently. Like O’Neill, there was a sense of a progress to her reading, particularly with regards to the interactions with Lohengrin. You could see in her face and her actions when the element of doubt started creeping in!

Romanian-Hungarian mezzo Judit Kutasi made an American and role debut as the villainous and power-hungry Ortrud … and what an absolutely marvelous debut it was! Quite possibly one of the most noteworthy US debuts in the recent years! While Ortrud tended to steal the show during any Lohengrin, Kutasi truly made the role her own, imbuing the role with a real sense of danger and menace and dialing down its usual campiness. Kutasi’s voice sounded dark, full, and round with a velvety quality that easily soared over the orchestra and the chorus with great control and vigor. Even more mesmerizing was her considerable acting; a true stage animal, she executed her two scenes in Act 2 with a fierceness and determination level seldom seen at War Memorial stage lately; a quiet storm during the confrontation with Telramund (staged brilliantly by Alden almost like a homage to Fifty Shades of Grey) and an exploding bomb during the cat-and-mouse game with Elsa (in a bachelorette party gone wrong kind of setting) before the end of Act 2. An accomplished Verdi mezzo as well, I truly wish we would experience her more in the future as SF Opera presents both Verdi and/or Wagner operas! On Sunday, the audience showered her with a long applause, for which she looked extremely touched and appreciative!

Brian Mulligan sang the King’s Herald in 2012 production, and this time around he made a role debut as Telramund, bringing his usual intensity and sonorous sound into his interpretation. His Telramund felt much more dignified than usual, almost as if he was a politician with over-ambitious wife, and his tableau with Ortrud was fascinating to watch. On the other hand, as the King Heinrich Kristinn Sigmundsson (who also sang the role in 2012) presented an emasculated version of the role splendidly both with his acting and with his voice, although unfortunately he could be hard to hear during ensemble pieces. Both these politician-like roles certainly added more food for thoughts for the second interpretation mentioned above! Baritone Thomas Lehman rounded out the main cast and gave a very impressive performance with his authoritative stance and booming voice in his SF debut as the King’s Herald, despite being dressed in shoulder cast and leg brace.

All in all, this was truly a superb achievement for San Francisco Opera and an auspicious first chapter in the Wagner opera journey with Kim. Hopefully, San Francisco Opera can maintain this level of showmanship for the future Wagner (and Verdi) presentations. There are only five more showings of this glorious performance, and you certainly don’t want to miss it! Or, at the very least, miss the livestream on Saturday October 21, 7pm PDT.

Photos: Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera

Comments