Tolomeo, HWV 25 is an opera seria in three acts with Italian libretto by Handel’s frequent collaborator Nicola Francesco Haym. Haym’s texts were adapted from the libretto of another opera, Domenico Scarlatti’s 1711 Tolomeo e Alessandro, ovvero la corona disprezzata, written by Carlo Sigismondo Capece. It was the final collaboration between Handel and Haym, as the librettist passed away the following year, ending one of opera world’s greatest collaborations.

Tolomeo was also the last of the five operas (started with 1726 Alessandro) Handel wrote for the famous operatic trio of that time, the castrato Francesco Bernardi (better known as Senesino), and “The Rival Queens”, sopranos Francesca Cuzzoni and Faustina Bordoni.

Since then, Tolomeo languished in oblivion till in 1939 Fritz Lehmann conducted the modern-day premiere as part of Göttingen International Handel Festival. Since then the performance history has been sparse; it was performed (and even recorded) during 1996 Halle Handel Festival with countertenor Axel Köhler as the title role, and most recently, in 2010 at Glimmerglass Opera (quite possibly the US premiere by a professional company) with Anthony Roth Constanzo.

Many Handel aficionados learned the opera from the 2008 landmark recording conducted by the late Alan Curtis, starring Baroque royalties Ann Hallenberg, Karina Gauvin and Anna Bonitatibus in the Senesino, Cuzzoni and Faustina (Bordoni went by her first name) respectively. Hallenberg is obviously the subject of my colleague Christopher Corwin’s recent feature article , and this recording clearly demonstrated her extraordinary talents particularly in approaching Baroque trouser roles.

Even more significant was that Curtis and Hallenberg (also as Tolomeo), in now long-deleted 2010 recording, gave us the only account of Scarlatti’s Tolomeo e Alessandro, one of Baroque opera recordings most desperately crying out for reissue.

The story of Tolomeo was based on fictionalized events of Ptolemy IX Lathyros, king of Egypt. Tolomeo (Ptolemy IX) was deposed by his mother Cleopatra (Cleopatra III) in favor for his brother Alessandro (Ptolemy X). (Cleopatra was a textbook murderous mother in operas; here she wasn’t a character, but everyone talks about her constantly.)

Tolomeo, his wife Seleuce and Alessandro ended up in Cyprus; all were damaged souls by the actions of Cleopatra. Cyprus’ ruler Araspe and his sister Elisa complicated things as they lusted for Seleuce and Tolomeo (now under the guises of Delia and Osmin) respectively.

Tolomeo’s story above didn’t necessarily make an easy translation into the stage, in my humble opinion. Most of the arias, particularly for Tolomeo, Seleuce and Alessandro, tend to be rather pensive and introspective, more descriptive of the inner turmoil of the hearts instead of advancing the story. On the other hand, it is very easy for the two “villains” (Araspe and Elisa) to turn into caricatures as their arias were filled with stereotypical manic and flirty gestures throughout.

Balancing those two aspects of the opera requires a sensitive approach from the director, besides the inherent Baroque opera “problems” of filling up the scenes during all those long da capo arias. The 2010 Glimmerglass Opera, for example, was widely criticized for turning the opera into all-out farce!

Benjamin Lazar, whose candle-lit historically informed staging for Riccardo Primo in 2014 Festival had captivated Karlsruhe audience before, returned this year to bring the plight of Tolomeo to life. In what constituted almost an antithesis to last year’s extravagant (some might even say excessive) Serse , Lazar set the whole opera in a single modern-day living room adorned with a couple of chairs and flower vases/plant pots by set designer Adeline Caron.

Sea, the element of nature that was specifically called out in the libretto (the whole Act 1 is set on the beach), was reflected by Yann Chapotel’s video on the background wall, which to me gave an effect that this room was seaside.

It didn’t help that the five singers were directed to be on stage all the time, with those not singing statuesquelyfacing the back wall! Since the Badisches Staatstheater stage is rather wide, the staging felt completely empty and inactive pretty much the whole opera!

However, Lazar’s direction wasn’t completely without merit. As Tolomeo drank the poison/sleeping potion, the back video showed big waves engulfing the whole set, and, in a pure stroke of genius, lighted “jellyfishes” came down from the ceiling and we were now transported deep under the sea. The transition, aided beautifully by Mael Iger’s lighting, made the moment feel purely magical, a perfect setting for Tolomeo’s heartbreaking stupor aria “Stille amare”.

Costume designer Alain Blanchot dressed the singers in modern working outfits, dominated by blazers and (leather) jackets, except for Elisa’s clothes that were adorned with Middle Eastern embroidery (no doubt to indicate that she was the Cyprian Princess). The earthy color palette employed by Blanchot was pretty telling; the purest of hearts (Tolomeo and Seleuce) were in off-white (later dark brown in their disguises), the ambiguous (Alessandro) in light green/blue covered in light brown overall, and the villains were in striking dark blue, turquoise and black.

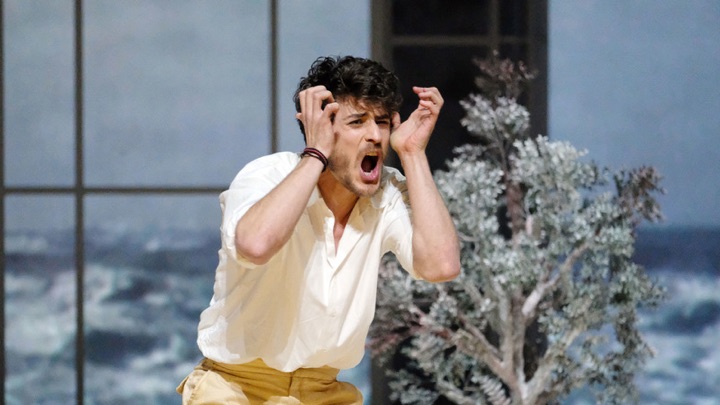

The stagnant staging unfortunately impacted the musical aspect somewhat negatively as well, at least on the opening night. From the moment Tolomeo was announced in last year Handel festival, it was designed as a vehicle for Polish countertenor (and breakdancer) Jakub Józef Orlinski, who made role debut as Tolomeo. Billed as the “shooting star” in the promotional material, his handsome face plastered all over the town drinking poison by the sea, no doubt contributing in popularity of the run.

Orlinski, with his a soft-grained voice, almost sounded puny at times, though that in itself wasn’t unsuitable as the suicide-prone anti-hero Tolomeo. (It was interesting fact to me that many of the roles that Handel wrote for Senesino seemed to be cut from this same cloth!) He, and pretty much everybody else on opening night, took a while to warm up, but he finally got comfortable in time for the crucial Act 3.

It was a pity that his movements (and again, everybody else) were rather poorly directed, in fact it became somewhat predictable – alternating between standing, walking, sitting and laying on the floor – robbing any tension that he tried so hard to build with his singing.

Louise Kemény, in Cuzzoni’s role as Tolomeo’s wife Seleuce, excelled that night. Her bright soprano voice sounded round and full, even hopeful, and she navigated her coloratura well, culminating in Act 3 aria “Voglio amore”.

During the after party following the opening night performance, Karlsruhe Festival artistic director Michael Fichtenholz explained how he went to Cesti competitions – the renowned International singing competition for Baroque operas – in search for the cast of the opera and he tapped three of them.

Morgan Pearse, winner of the 2016 competition, impressed me most with his take on the villainous role, Araspe. Written for Giuseppe Maria Boschi, famous for his “rage arias”, Handel gave Araspe three such arias and they were bound to make significant impact if performed well. Singing with compelling presence and considerable ease, Pearse completely stole the show every time he appeared. He felt like a breath of fresh air, particularly in Act 2 “Piangi pur” shortly before the break.

Meili Li, “the first Chinese countertenor to have received a conservatoire education” according to OperaWire, assumed the tricky role of Tolomeo’s brother Alessandro. His voice imbued with warmth that was very appealing and differed from Orlinski’s. On that night he seemed a little bit tentative in his movements, most probably caused by opening night nerves.

The Italian conductor Federico Maria Sardelli made an opera debut conducting Deutsche Händel-Solisten with these performances, having conducted a concert five years prior. After having a little synchronization problem during the Overture, he led the whole proceeding proficiently, if not terribly exciting to my ears. However, I had to point out that he did the aforementioned “Piangi pur” and “Inumano fratel, barbara madre” brilliantly, and they were definitely the highlights.

It was great that Karlsruhe Handel Festival finally presented this problematic opera. I just wished the performance wasn’t so underwhelming. Nevertheless, next year they will present staged version of Handel’s oratorio Hercules, with none other than Hallenberg as Dejanira, and directed by Floris Visser, who triumphed last year with Vivaldi’s Juditha triumphans.

Comments