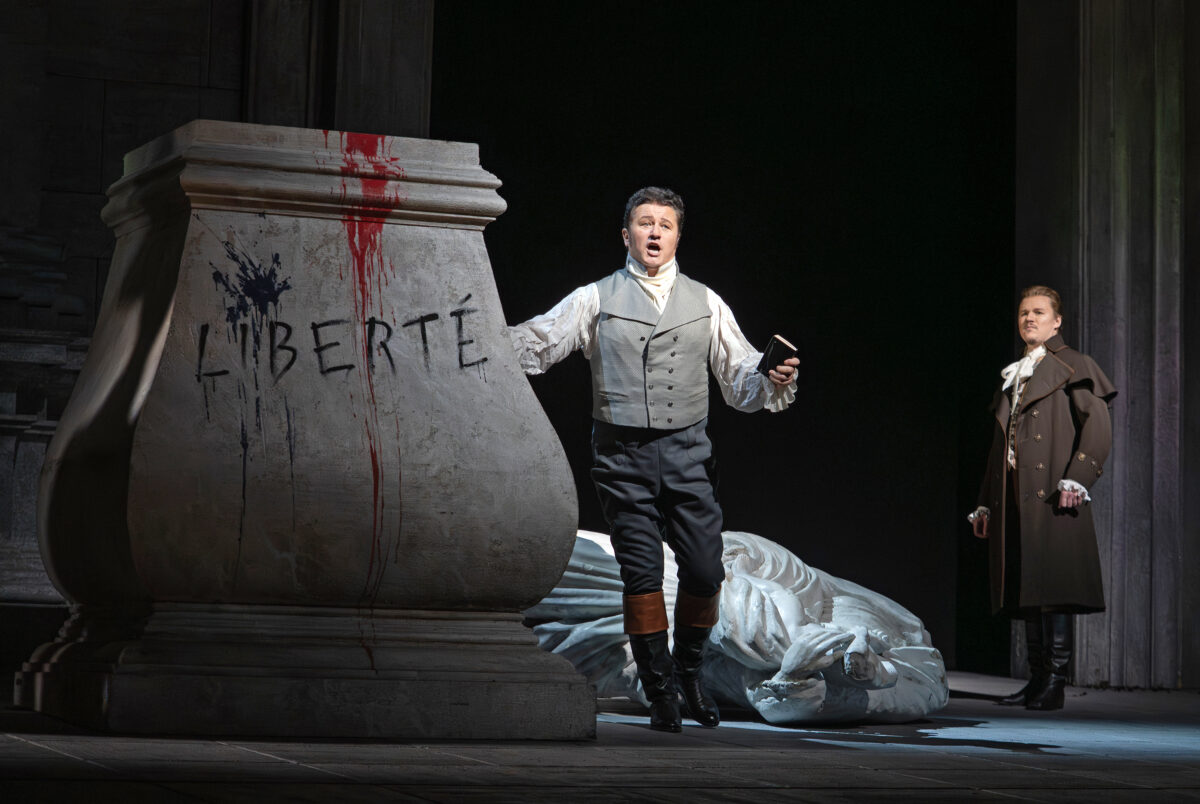

Piotr Beczała as Andrea Chénier and Guriy Gurev as Roucher in Giordano’s “Andrea Chénier.” Photo: Karen Almond / Met Opera

Giordano’s Andrea Chénier is a feast for opera lovers, voice lovers, and opera singers.

And they have good reason to love it, especially tenor fans. The good tunes are endless: often, a great tune will show up in the background, only to be casually tossed aside for another. The tenor has a spotlight solo aria in each act in various modes—heroic, lyrical, reflective, etc. The baritone and soprano each have a showstopper aria where tears, blood, and guts are left on the stage.The storyline is strong, historically grounded but not pedantic, and has vibrant confrontations throughout, building up to a soaring double death scene full of blazing high B’s for the soprano and tenor.

Mainly, the work is a vehicle for opera stars and stellar Italianate voices—something that is in short supply these days. When the work was introduced to the Met in 1921, those voices were profusely supplied. The work disappeared from the Met stage after 1933, until another operatic golden age took shape in the 1950s. Mario Del Monaco brought the opera back to the Met in 1954 with Zinka Milanov and Leonard Warren in tow. Renata Tebaldi and New York local boy Richard Tucker returned for many revivals with Ettore Bastianini as Carlo Gérard. The 1960s had Franco Corelli owning the role of Chénier for seven performances. By the 1970s, the revivals and the voices were scarcer on the ground, with Plácido Domingo and Carlo Bergonzi appearing in 1971 and 1977.

Then there was a big break until the 1990-1991 season, in which the Met borrowed a Wolfram Skalicki production from San Francisco starring Nicola Martinucci and Aprile Millo, with all the attention going to Sherrill Milnes in his 25th season with the company.

A scene from Giordano’s “Andrea Chénier.” Photo: Karen Almond / Met Opera

The current production by Nicolas Joël, featuring sets and costumes by Hubert Monloup, was first mounted by the Metropolitan Opera for the role debut of Luciano Pavarotti, who was over 60 at the time. James Levine conducted, and Aprile Millo returned as Maddalena. Now, Pavarotti was not going to do an avant-garde production (let’s say staged like Marat/Sade in an insane asylum) nor was he going to do anything physically strenuous; as I remember, he ambled through the role amiably playing himself. The production is at once minimalistic with a few set pieces and spartan decoration while still trying to look period and detailed. It has the weird combination of looking cheap and frilly at the same time. For having what seems to be fairly lightweight Styrofoam sets, the intermissions were long and fatiguing—and frequently longer than the acts themselves.

If you just accept the Joël staging as a backdrop for bravura performances, then it suffices. However the last revival in the 2014 season had less than bravura performances from veteran lyric singers who were both overparted and underdone in the lead roles. Let’s pass over in silence the 2002 revival with a 60-something Domingo attempting to recapture his earlier glory days with radically lowered keys and a recomposed “Come un bel dì di Maggio” that had to be heard to be believed.

Maybe the era of Andrea Chénier and that kind of star power was over…

Having never heard Tucker, Corelli, or Tebaldi, I am not haunted by my own youthful memories, and the 2025 lineup of Piotr Beczala, Sonya Yoncheva, and Igor Golovatenko seemed promising to me. Heard on opening night November 24th, the star trio in their different ways delivered a stylish and movingly sung performance, though the two leads are somewhat past their first vocal freshness. It had to be better than what came before it in the last 25 years.

At his first act entrance, Golovatenko delivered Carlo Gérard’s bitter tirade at the excesses of the aristocracy with a stentorian and stinging tone full of vibrancy. He made a strong opening impression and kept it up all night long. This is the kind of no-holds-barred vocalism this opera thrives on. Yes, his vowels could be more open and Italianate and, yes he could have tempered his dynamics more consistently. But his “Nemico della patria” in Act III won a well-deserved ovation. Carlo’s sudden conversion to selfless compassion and his decision to save Chénier were moving and convincing. This may be Golovatenko’s best work at the Met so far.

Yoncheva was harder to assess; her register breaks, not always well-controlled vibrato, and tonal wear may have exacerbated over the audio stream. Most of Maddalena’s music sits in the middle range until the climax of the big Act III aria and the final duet. In the house, the smoky vocal color had a Cetra soprano quality to it and she phrased with some elegance and style. Yoncheva acted movingly with her face and body and looked handsome onstage.

Sonya Yoncheva as Maddalena in Giordano’s “Andrea Chénier.” Photo: Karen Almond / Met Opera

In “La Mamma Morta” the opening lowish declamation in the narrative was effective if a bit tonally hollow. She did put over the text. The big climax sounded careful and a bit thin (Yoncheva, like most current sopranos, takes the optional higher final phrases with a concert ending tacked on rather than descending into the lower depths). The final high Bs of “Vicino a te” were confident if a bit metallic.

However, it is now a brittle sound that cannot take pressure and does not have much in reserve. There was a consistent element of pushing through without much plushness of tone underneath. Yoncheva is only 44, but she seemed like a canny veteran powering through while conserving and consolidating what voice she has left. In the theater, her vocal fragility was moving, adding vulnerability. Under the scrutiny of the microphone and without the visual element, it might not work as well.

The raison d’être for this opera is to showcase a star tenor. Beczala, despite turning 59 at the end of December, was a dashing and radiant vocal and physical presence despite some initial dryness that dissipated before his Act I “Improvviso.” The aria “Colpito qui m’avete… Un dì all’azzurro spazio” began rather lyrically, giving Beczala room to build to a defiant and declamatory climax. “Come un bel dì di Maggio” showcased his bel canto skills and was maybe his best work all night. The silvery ring and golden warmth Beczala has brought to more lyrical repertoire was evident here along with a heroic aspect. He is always an elegant and musical singer, never bellowing his way through the role as lesser tenors have, nor was he ever underpowered. Beczala also cut a handsome figure onstage. I am glad this will be streamed in HD on December 13th.

There were vocally promising debuts by Siphokazi Molteno and Guriy Gurev as Bersi and Roucher, while Nancy Fabiola Herrera made the most of the Contessa di Coigny. Tenor Brenton Ryan was a sinuous Incredibile with a blessed lack of the usual unpleasant nasal tone. Oleysia Petrova’s vocal richness, tonal poise and innate dignity made Madelon’s incursion into Act III’s Revolutionary Tribunal a moment of pathos, rather than bathos. Bass Maurizio Mauro sounded a bit crusty as Mathieu, but he is a bit of a crusty fellow, isn’t he?

The real hero was in the pit, as new principal guest conductor Daniele Rustioni revealed more of his artistic virtues than he did in Mozart earlier this month. Rustioni showed real love for this veristic gem, relishing its vibrant orchestration and dramatic details while giving the singers all the help and room they needed to carry the evening.

So no, the singers weren’t as vocally impressive and Italianate as Corelli, Tebaldi, Bastianini et al. But they had enough vocal and dramatic presence and engagement for their roles. Everyone sang in their best current form and delivered moving performances in the right style. Beczala is currently, in my estimation, a genuine star Chénier despite his veteran status. The production is what it is. It did not get in the way of the singers or the opera. Rustioni conducted like one of those great old Italian masters of the verismo game like Gavazzeni or Serafin and the orchestra played superbly for him.

There is enough good singing up there so that the opera is well served and it was a fun evening out. It showed that a fine and enjoyable Andrea Chénier experience is still possible in this new century; no need to live in the past.