Photo: Lawrence Sumulong

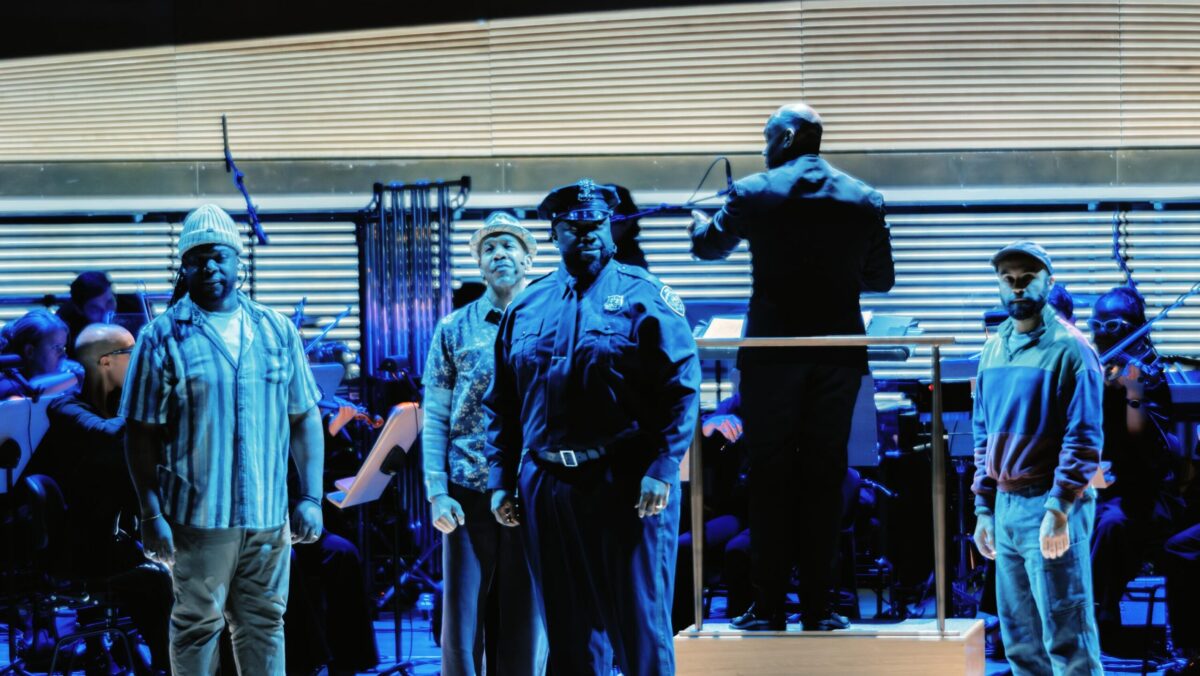

Lincoln Center has named composer Jeanine Tesori as this season’s Lincoln Center Visionary Artist and they have a season’s worth of activities planned in her honor, including a staged performance of her opera Blue in David Geffen Hall on Saturday 15 November. This was co-sponsored by Lincoln Center and the Metropolitan Opera, even though I found no mention of it on the Met’s website. However, members of the Met’s management team participated in the press briefing before the show.

Blue was commissioned by Glimmerglass Opera in 2015. Francesca Zambello, the Artistic Director at the time, wanted to create an opera that addressed contemporary issues around race in America. For this, she brought together composer Tesori and playwright/director Tazewell Thompson who wrote the libretto and directed the world premiere. They created a powerful work about an African American family in Harlem where the father is a police officer. The parents strive to keep their activist son safe, but the son continues to protest racial and economic injustice and is shot and killed by the NYPD.

There is so much dramatic and thematic potential in this scenario; too much, in fact, to fit into a two-hour opera that covers The Son’s entire life and the aftermath of his death. We do not see the exact circumstances of The Son’s death or even learn his name, as the characters in this show have no names, just titles. The show teases a potential plotline when The Father goes to a church to speak to The Reverend about his unfathomable loss and boundless rage and, while there, vows to shoot the white officer who shot his son, waving his officer’s revolver to show the sincerity of his threat.

Photo: Lawrence Sumulong

Nothing comes of this. While I did not need (or want) to see The Father go full Coalhouse Walker (Ragtime is already playing next door at Lincoln Center Theater), we do need to see Chekov’s gun get put away and understand whether The Father comes to terms with his profession as a police officer and the institutional racism of the NYPD. Instead, the work almost becomes an oratorio with more poetic language and prayerful laments. This includes several intensely emotional choral passages that were the highlight of the work for me.

At the very end, after a final prayerful moment, The Son is back at the kitchen table with his parents. His mother has conjured up a majestic spread using, it seems, the entire contents of the Witch’s garden in Into the Woods. He announces his plans to go to art school and attend one more “peaceful” protest where he insists, without any orchestral accompaniment, that “Nothing will happen.” Is this a flashback to just before his death or a glimpse into the alternative future that should not have been stolen from him? Either way, the work ends in quiet ambiguity with no resolution to its conflicts or any available path forward for his parents; this is the only possible ending in today’s culture.

Even with the dramatic challenges, there is a lot of moving, well-crafted music in this piece, particularly in the second half. Amongst active composers, Tesori is unmatched in her ability to meld music in different styles into a coherent whole and the opera deserves a fuller production in New York. (It has already received full stagings in Chicago and Washington, DC.) While the performance was billed as “staged with direction by Tazewell Thompson,” the playing area was very constricted and the performers were very focused on their scores, even during physical confrontations. Even with that significant constraint, the performers gave committed, impressively realized interpretations

Unfortunately, they were completely undermined by Richie Clarke‘s amplification and sound design of the performance. From what I can tell, previous incarnations of Blue used mostly opera singers and had no amplification. For this outing, the cast had a mix of music theater and opera singers and they were all very heavily amplified to the point that their singing was distorted, balances were off, climaxes were congested, and nuances were lost in the clangor.

Photo: Lawrence Sumulong

I’ve heard many amplified performances. In the best engineered ones, the performers’ voices seem to originate from their location on stage with the amplification reinforcing their basic sound. From where I was sitting in the back, there was no sense of the performers’ locations or their voices filling the hall; it was just a wall of ill-balanced sound. I could understand how some amplification might have been warranted given the cast and the configuration for the performance, but the sound design failed the work and performers.

I am reluctant to evaluate the singers under these circumstances, but I do hope to hear the main performers again under more felicitous conditions. Tamar Greene was The Father and he fared the best in the inhospitable acoustics, potently capturing his character’s pain and conflicts. Tamara Jade was the Mother, surmounting the considerable emotional challenges of her second Act lament.

Philip Boykin, as The Reverend, has a large body of work familiar to NYC theater goers. He provided the necessary gravitas and emotional grounding for his crucial role in Act II. And as The Son, Mason Reeves captured his character’s sullen, combative determination deftly and was convincing as a teenager, even if this linchpin character has a surprisingly small part in the opera itself. The several-hundred-person-large choir, conducted by Joseph Young, was completely uncredited in the program — strangely, there was no bio for the conductor in the program, either. Nevertheless, he deftly navigated the many styles of the work and surely charted a course to the emotional climaxes, even if his control of balance was at the mercy of the sound engineer.

There is a recording available of the opera from its run at the Washington National Opera in a performance a bit more stodgy than the one heard on Saturday. The work does benefit from the skilled musical theater actors I heard, but those performers and the work need to be seen and heard under better conditions.