Yet the full impact of this vital and timely subject matter feels frustrated at times by a libretto that doesn’t effectively tie the work’s episodes of cathartic emotion into a cohesive whole.

The libretto opens on the pregnant Mother (the characters are left unnamed) and her three girlfriends, who find out to their dismay that the child’s father is a police officer, and that the child is a boy, warning that he is destined to a life of persecution. While this scene works well enough on its own, it soon becomes clear that Act I is content to rest on these broad facts about the characters for any sense of conflict.

Most of the Act I material feels dramatically inert, with stretches devoted to domestic scenes of the Father with his own group of three buddies, and the Father and Mother in the hospital. These scenes seem intended to increase our sympathy with the parents in advance of the coming tragedy, but in practice they feel aimless, a missed opportunity to let us learn about the characters through specific moments of conflict and tension, however small.

Act I’s final scene abruptly skips forward from the Son’s birth to his teenage years, dropping the audience into a bitter confrontation between the Son and the Father about the Son’s involvements in protests and petty crimes.

The libretto gives us little help in understanding the Son in this scene with thorny dialogue that largely consists of sophisticated political analysis or indictments of the Father’s role in the white power structure, while the few personal motivations we do hear ring false. (Would this rage-filled, politically activated teenager really berate their parent for not having given them a little sister?)

Act II opens after the son has been killed, by one of the Father’s white fellow police officers. In perhaps the most intriguing and nuanced scene in the show, the Father reveals to the Reverend some of the details of what has happened, unburdening himself about his crisis of faith and his plans to exact vengeance on the white police officer, though this potentially interesting plot line is never pursued.

The balance of Act II, including a scene for the mother and her girlfriends, and a long ensemble section at the Son’s funeral, operates at an agonizing emotional pitch, as the parents come to terms with the loss of their child and the injustice of his death.

While the cast effectively pushes these sections to the limits of despair, these expressions of grief feel both overwhelming and yet oddly hollow in the absence of a well-developed story to bring us to this point, leaving one to wonder whether a direct meditation on the tragedies that inspired the work might have served these themes more effectively than a work of fiction.

The final scene of the opera provides us with a belated additional glimpse of the Son’s character, in a flashback to the moments after Act I’s confrontation, set amidst the funeral set piece that has just concluded.

Moments after that bitter exchange, we see the family saying grace together and the Son beaming that a teacher has told him his latest art project will help him get into the Rhode Island School of Design, before earnestly asking the Father for permission to attend another upcoming protest, which the libretto and music intimates is where the Son was killed.

This seems intended as a final coup to inspire the audience’s pity, as we now learn that the murdered Son was actually a tremendously sympathetic character. But it feels as though the libretto is again seeking to stir our emotions without having done the harder work of developing a plausible character arc from the outset.

More mundane issues in the libretto sap the work’s impact as well. Several scenes linger too long on formulaic beats that don’t advance the story, from the comedic bits around the Father’s reticence with the newborn to the Fathers’ buddies’ obsession with football.

The text also frequently falls back on using lists in the place of more meaningful lyrics. In the flashback in the closing moments of the show, just as we think we might finally see a direct interaction between the Mother and the Son, the vast majority of her closing aria is devoted to simply listing beloved dishes that she cooks for her family.

Sudden shifts between the characters’ plain-spoken dialogue and passages of high-flown poetry can also feel forced instead of organically elevating the characters’ expression.

Tesori, best known for her successes in musical theater, delivers an engaging score rich in musical ideas for her first full-length opera. The vocal writing for the principals does much to create distinct impressions for each character, and passages for ensembles are particularly fine, from the creative handling of the two trios of friends to the memorable climactic chorus scene.

Orchestral colors often bring forward winds and horns in layered textures lightly reminiscent of Aaron Copland, particularly in a number of the compelling interludes between scenes. The score also includes departures from its basic neo-romantic palette with jazzy interjections, the use of a drum kit to add a harder-edged, more contemporary sound, and the unnerving percussive effects that open the piece.

At times, however, this surfeit of ideas made it difficult to find a musical through line to tie the piece together, both as a whole and on a scene-by-scene basis. While sequences consistently offered exciting musical depictions of emotional high points, there was less focus on building climaxes and developing musical ideas over longer stretches.

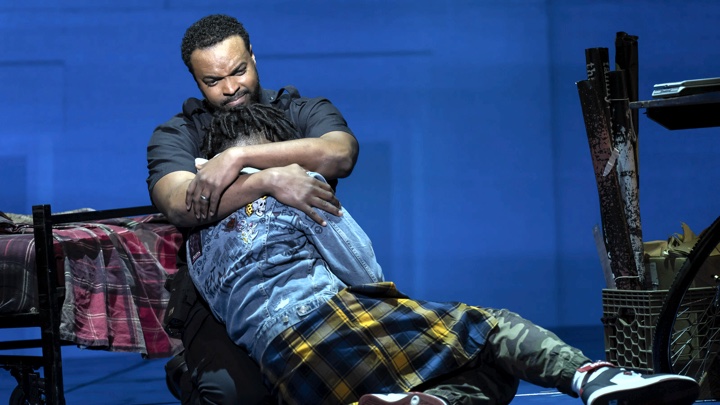

A dynamic cast of singers did much to bring warmth and pathos to Blue’s story and music. Kenneth Kellogg, a graduate of WNO’s young artist program and frequent presence in D.C., brought his distinctive, earthen bass and a commanding stage presence to the role of the Father, projecting determination and barely controlled anguish in his confrontation with the Son and confessional scene with the Reverend.

As the Mother, mezzo-soprano Briana Hunter shone in some of Tesori’s most lyrical vocal writing in Act I, extending an urgent, solid core of sound upward to thrilling effect in passages reflecting the Mother’s optimism about her child. Her searing rendition of Tesori’s tour de force Act II aria for the Mother showcased a range of strengths from a formidable chest voice to a blazing upper register.

Tenor Aaron Crouch brought a bright, incisive color to the relentless spiky figures that Tesori uses to capture the Son’s anger in his primary scene with the Father. Though initially coming off as a notch quieter than the rest of the cast, he was able to adjust to the right volume for the more intimate Eisenhower (the Kennedy Center’s Broadway-style theater). Joshua Conyers’ mellow, sweet-sounding baritone made for an effective vocal contrast with Kellogg’s acid portrayal of the Father in crisis.

The rest of the cast played the friend groups of the Mother and Father along with several dual roles. The women in particular, soprano Ariana Wehr, soprano Katerina Burton and mezzo Rehanna Thelwell made much of the two extended scenes for the trio of girlfriends, who act as a sort of Greek chorus to the Mother, gamely handling comedic interactions in Act I and harrowing lamentations in Act II. Other notable turns included Wehr’s dazzling high notes as a nurse in Act I and tenor Cameron Gray’s pleasing sound as a soloist at the funeral.

Thompson’s direction was natural and effective in the largely straightforward scenes, though the production might have benefited from building on some of the more theatrical touches, like the Father’s initial dressing in his police uniform amidst eerie blue lighting.

The main gesture of the simple set presents a row of brownstones in relief on an all-white backdrop which proved surprisingly versatile in the effects it could convey to support the action, thanks to creative lighting by Robert Wierzel.

Photos by Scott Suchman

Comments