Javier Del Real

If we wanna get a lil’ idealist with it, let’s say there are transcendent performances – performances that overwhelm, take us beyond ourselves and drop us off, changed, at the other end – and sublime performances – performances where we can bristle and thrill to what we see and hear all the while remembering we are watching a great performance of something, usually of a great work. (The is to say nothing of the mid or outright disappointing performances!)

I felt this double-remove during last week’s strong performance of Otello at Madrid’s Teatro Real, its season-opening production which was often sublime. Here, Brian Jagde was trying his hand at the ‘Esultate,’ an outing complete enough to do justice to a tremendous role though not quite fully formed. While a strong and engaged actor, Jagde seemed far more at ease playing the feral Otello driven insane by jealousy and suspicion than he did as the more ardent romantic hero. This gave him plenty of space to grow from Act I, where the role was packed into his middle voice to the detriment of a sense of vocal line. The sound itself is more a trombone than a trumpet, giving Otello’s brooding sottovoce moments like “Dio mi potevi scagliar” greater effect than the declamatory proclamations. The vocal effects don’t always land, but it was more than enough to provide a sense of Verdi’s achievement and Jagde’s ambition. Hopefully it’s a role he’ll grow with some more.

Opposite him was the enigmatic Asmik Grigorian in an unpredictable role for the ballyhooed stage animal. (Desdemona is courteous, cordial, and upright, whereas Grigorian specializes in women about to blow their stacks.) Grigorian’s Desdemona is mousy and timid, her cowering interactions with an unhinged Jagde suggesting that this Desdemona was no stranger to spousal abuse. When Otello, humiliating his wife in front of the delegation from Venice, orders, “A terra!… e piangi!” Grigorian sunk with such a slow sadness you wondered if she’d ever make it down – or up again.

Vocally, she’s in fine shape with perhaps her greatest asset as a musician, even beyond the steadiness of her warm timbre, being the decisiveness of her singing. Like Jagde, not every vocal choice pans out – if you were curious about what a Desdemona without a floated pianissimo sounds like, look no further – but they are all firmly made and she sings the Willow Song with a glassy tone and such incantational fixity you half expect the tree to sprout up right in front of you.

Gabriele Viviani is set against them as an extrovertedly villainous Iago and his confident, communicative singing was nicely showed off in the Credo and in the smaller roles, Albert Casals was a gallant Rodrigo while Enkelejda Shkoza sang expansively as Emilia. The production is the same David Alden production that has previously been seen in Washington, amongst other cities (including in Madrid nine years ago), though now more fully realized, its vague updating to early twentieth century begetting some awkward Zorba the Greek choreography (by Maxine Braham) and a particularly ugly pair of culottes for Emilia (by Jon Morrell, who also did the barebones scenery). Alden’s production thinks more with Verdi’s score here than it did in Washington, sometimes relocating the chorus from the stage to give the action of the soloists a dreamy quality, and the singers, Grigorian especially, seem responsive to the way he maps out the grander moments.

But more adept at drawing contrasts was Nicola Luisotti whose conducting was especially evocative in its transitions between the more vast and the more intimate moments of the score. Equally firm was the chorus which sang with a detailed blend and granite-like security. A comparatively newer opera company in Europe, the Real has proven itself both ambitious and savvy through eclectic projects cast creatively and a strong orchestra and chorus. This Otello, fresh and thoughtful, was just one example.

Roberto Ricci

In Parma, at the opening of the Festival Verdi, the Otello performance that came five days after my Madrid performance mostly skirted the sublime/transcendent binary. The Festival Verdi itself, of course, is a ball – the entire city of Parma is overrun with events, installations, and public programming to complement performances at the Teatro Regio di Parma and the far-flung jewel box Teatro Verdi in the Busseto city hall. (The family programming of the Festival, from infants to adolescents, was based around the corner from my Airbnb in a decorated yurt called “La Yurta di Peppino.”)

But its new Otello was more of a mixed bag with its biggest liability at its center, the Otello of Fabio Sartori. One can imagine a time when, for one reason or another, Sartori might have been hailed as another Pavarotti minus the tonal opulence. Here, he is uncomfortable and wooden, essentially unable to act and often straining to reach at the top notes. His overwhelming inhibitions are a shame, because his phrasing, especially in Otello’s more tender moments, can be gentle and in moments of anguish, he really does seem swept up by the music and the singing miraculously improves. But this was park-n-bark of the old school, only without the old-school polish.

Mariangela Sicilia had more of that polish as a spitfire Desdemona, but she, too, was incomplete. The glory of the voice, conversely from Grigorian, is the high pianissimo, an effortlessly accessed fil di voce that defies comparisons with most other singers on the market now. But beyond that, there’s not much to the middle voice and practically nothing at the bottom. Yes, Desdemona can and should float beautiful lines in the Love Duet and the Ave Maria, but if she can’t also provide some grit then what’s the point? When she didn’t make anything of her rejection of that “parola orrenda” in rebuffing Otello’s accusation of infidelity, of being a “vil cortigiana,” in Act III, I lost interest.

Roberto Ricci

The standout of Friday’s performance turned out to be the Mongolian baritone Ariunbaatar Ganbaatar as Iago, a fine, understated actor with a handsome and wisely wielded instrument. He balances harsh declamation with note-perfect singing, the Credo in particular coming off with an ease and suaveness that hinted at what lay beneath this Iago’s more placid veneer. Sophisticated as an actor and scrupulous as a singer, this is a talent to watch.

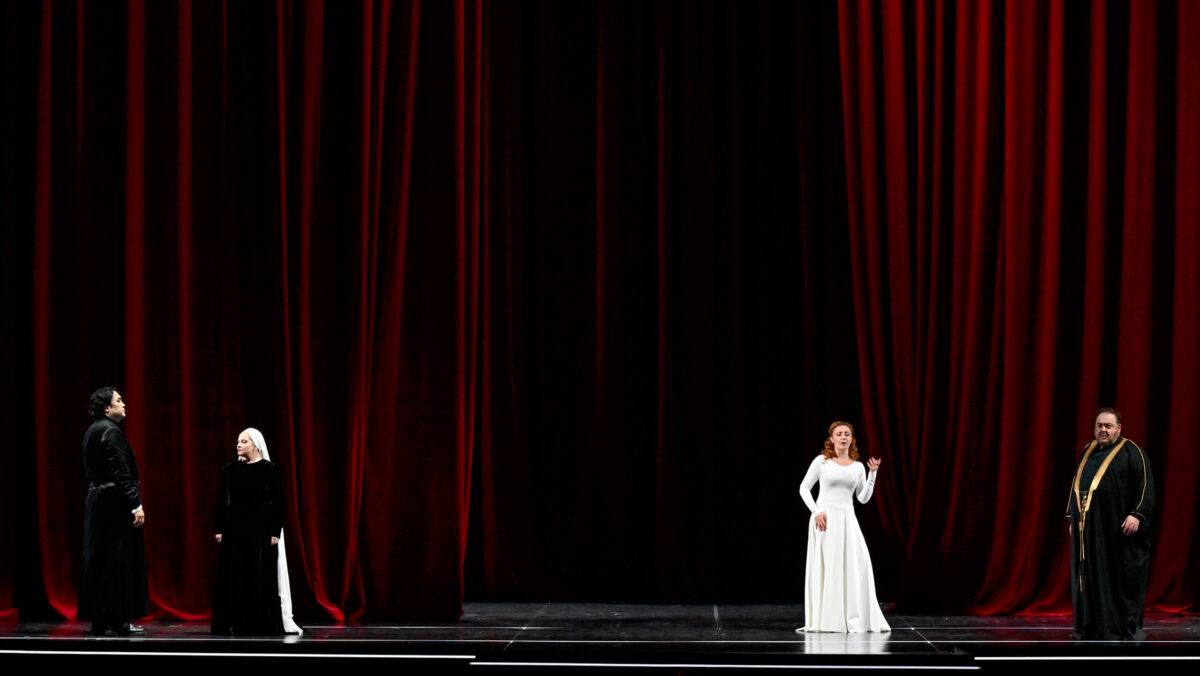

Daniele Abbado held them together above an unrelentingly rich, cohesive orchestral texture, but there was a lack of frisson between the conductor and the soloists; whether the orchestra was actually arriving at the score’s climactic moments a split-second ahead of the singers or it just felt like that, the performance lacked a spontaneity. It hit its marks, but never truly came alive. Federico Tiezzi’s production was no help, largely confined to traffic direction on an empty stage around spare tables and curtains designed by Margherita Palli. By the time Desdemona’s highly detailed, Edward Hopper-esque bedroom diorama loudly rolled onstage it was too little, too late.

But despite the shortcomings of the performance, Otello is still Otello, great and fearful. It’s hardly an impervious opera (see: Eugene Onegin), but in a competent enough outing its genius still flares brightly. Otello in Parma was far from the sublime of the Otello in Madrid, but in both places Verdi’s score shone through as transcendent.