Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera

Though an art form devoted to bigness, sometimes it’s the smallest moments in opera that are the most impactful. Isolde’s final word on love is a floated cry of “Bliss!” at the end of Tristan und Isolde. When the humbled Count Almaviva needs his wife’s forgiveness in The Marriage of Figaro, all he can say is “Countess, forgive me.”

Near the end of Act I of Jake Heggie and Terrance McNally’s Dead Man Walking, Sister Helen Prejean can only muster, “I’m sorry, I’m so sorry,” when confronted by the parents of the victims of Joseph DeRocher, the killer whose soul she is trying to turn toward truth. Despite the overarching tempest of Heggie’s score, it’s in these small, almost missable moments that the opera, like the warmly received revival that opened at San Francisco Opera on Sunday, truly shines.

Dead Man Walking is San Francisco Opera’s first revival of a work it commissioned and premiered 25 years ago next month. The company is a national leader in new work, having commissioned no fewer than 30 new operas since 1923, an average of a new opera every four years. None has seen the successful afterlife of Dead Man Walking. 150 productions since 2000, and going strong. Next month they will give the world premiere of Huang Ruo’s and David Henry Hwang’s The Monkey King.

I first saw the Dead Man Walking 25 years ago at the War Memorial Opera House on another opening night. It was an engrossing piece of theatre; Terrence McNally’s libretto is one of the best of any opera of the 21st century, but my main concern was that, musically, it wasn’t a very memorable work. And after hearing it again, I left with the same opinion.

As is the case with a lot of mainstream contemporary operas, Heggie’s writing tends to be the same from scene to scene. A vocal line will start in the middle voice, then build to a ringing crescendo into the singer’s upper range, then the tension is let out and we start over again. Its most memorable melody, “He will gather us around,” is one that, though original, essentially borrows from the spiritual tradition. The rest is tastefully tonal yet lumbering, as if Puccini were filtered through John Adams. Heggie could learn from these composers about the importance of rests, of giving us moments to chew on things. Heggie, honorably, wants to communicate the emotional weight of the subject but never relieves us of it long enough to give us any perspective. The small, poignant moments throughout the score are effective and we need more of them.

Sister Helen’s plaintive “I’m sorry, I’m so sorry,” in mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton’s gentle reading of the line, is so devastating to watch because it’s a moment where performance stops. Sister Helen just doesn’t know what to say or what to do. She’s lost. In many ways, so are we, as we struggle to hate the sin but, somehow, not hate the sinner. I wish Heggie had trusted himself to back off the gas pedal like he did in that scene.

Yet there are several compelling moments in the score, like the sextet near the end of the first Act. It comes closest to letting us process what’s going on. It recalls the bel canto tradition of Donizetti or Bellini which Heggie turns into a fugue-like meditation on evil and grace. It was the longest scene in which the writing for the singers both challenged them but also played to their strengths. I so wish Heggie would have done something this again in the second Act nearer the execution. Another moment of particular beauty comes when Sister Rose, a resplendent Brittany Renee in a role that should get her hired everywhere, comforts Sister Helen late at night. Heggie’s writing for the soprano voice here is nearly perfect, an almost Straussian outpouring of honesty and genuineness but is somehow so gentle.

Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera

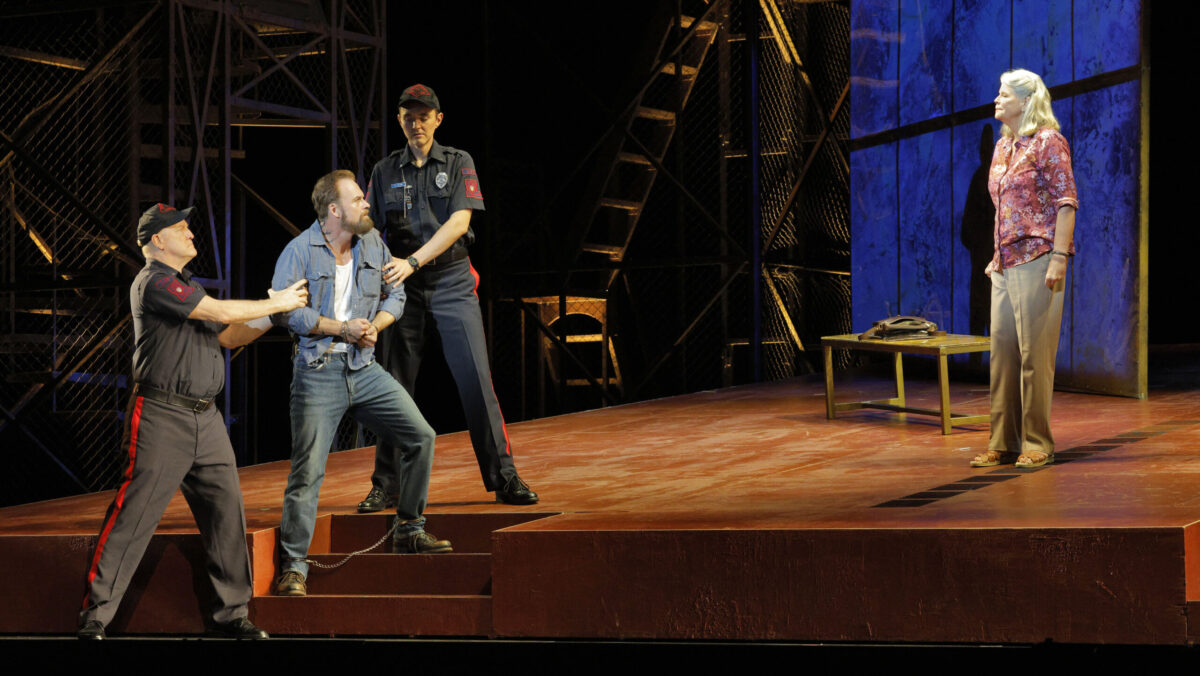

San Francisco Opera has imported the much-traveled Leonard Foglia production, currently owned by Lyric Opera of Chicago and created by a consortium of American companies, some of which no longer exist. It’s a fleet and efficient staging that has been somewhat awkwardly adapted to the vastness of the War Memorial. For all its moving parts, the production is personal and unfussy. Characters sing to each other, not at each other. Big moments are handled with class but not robbed of their emotionality, even if it’s often created through the score’s sheer loudness. Foglia and associate director Katrina Bachus have wisely moved the action downstage, closer to the audience in an opera that, for all its sweep, is really a chamber work and the balance they strike mostly works. There are some crunchy moments — watching an opera chorus play prison thugs who seem never to have seen a basketball in their lives will always be cringey — yet, on balance, the opera as a captivating work of theatre held together.

Transitions between Michael McGarty’s realistic sets are swift, allowing for tension to continue building in each Act. Flying chain-link fences and lighting fixtures divide the spaces, even briefly imprisoning various characters as they transition to their next scene, a subtle and clever touch. Brian Nason’s lighting is at turns stark white then saturated greens and golds and reds that flatten out the set and make it look more like a funhouse than a prison. Those moments of starkness were so powerful that they made the bright colors only more disjointed. Jess Goldstein’s effective costumes captured the mid-1990s, even if some of the dresses dated much further back.

Jamie Barton is singing Sister Helen for only the second time in her career. Her take on the role is honest and straightforward, almost demure in places. She inhabits the role of a nun without any hard-edged cliches or syrupy, elementary-school-teacher fakery. In fact, there were moments in which I wished she claimed more of the stage. Of course, that refusal to suck the air out of the room made her confrontation with the victims’ parents — “I’m sorry” — that much more heartbreaking. Barton was no diva fending off vicious attacks. She was contrite, trying to figure out what she was even doing there in the first place. It wasn’t her scene, it belonged to the victims. Not many singers would give that space to other singers.

Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera

Barton has a rich, flexible voice, but Sister Helen is not a role tailored exactly to her strengths. It was written for Susan Graham (also in this production) whose voice sits higher. Barton’s voice does not, and though she has sung roles that straddle mezzo and soprano, her voice has matured beautifully into a solidly mezzo voice. Heggie’s writing in Dead Man Walking lies right at the top of Barton’s instrument, and though she never really lost the pitch, the voice becomes metallic way up there. Even so, her stage presence is winning. We need to trust Sister Helen. And we do.

Opposite her was baritone Ryan McKinny. He has performed Joseph DeRocher at the big three American opera houses (San Francisco, Chicago, Metropolitan) and I could almost say exactly about him what I said about Jamie Barton. His DeRocher was just as likely to cede the stage to others as he was to claim it. It got to the point where I forgot several times that he committed murder and sexual assault right in front of us at the top of the opera. In a sense, this was refreshing. We don’t need a cartoon villain. We need a lost and terrified man-child who killed because he wrongly decided that he had something to prove, even if he didn’t know what that was. But I also wanted a bigger arc for DeRocher. McKinny’s DeRocher began the opera awkward and hapless and ended the opera the same way. Vocally, the part is a good match, but the acoustics of the War Memorial are tricky, leaving him barking the role to be heard, distorting his sound, and creating some odd vowels along the way.

But the day belonged to Susan Graham. She created the role of Helen Prejean a quarter century ago and now sings the role of DeRocher’s mother. Her entrance into the opera is perhaps the best moment of the whole thing. We hear her spoken voice first as she walks into a parole board hearing. She fumbles with a letter she wants to read aloud. Her gait is halting, a child being summoned to the principal’s office. It was a master class in physical acting. Graham’s voice still shimmers, even as it climbs, its age only making it more clarion, more characterful. She was a great match with Barton, two mezzos with voices that can hold a room. As the opera went on, Graham’s character became more and more fragile, refusing to hear her son’s confession for fear of hearing the truth. Her hand would rub her abdomen absently, almost ready to shield her solar plexus from the blow she knows is coming: her son has to die and he actually did the thing he’s accused of doing. I’ve coached and taught actors for a long time, and this was a performance I would make even non-singing actors watch over and over again.

Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera

I must celebrate another San Francisco Opera veteran: the baritone Rod Gilfry as the father of one of the victims. Most recently he was featured at the War Memorial in the American premiere of Innocence and he continues to shine in character roles that still need to be sung fully. His take on the understandably angry father of a murdered girl was somehow as classy as it was raw. He indulged in the man’s hurt and the anger, even in moments of blistering unfairness to Sister Helen. The voice is big but precise with excellent diction, a skill he shares with Barton and Graham. His face became a Greek mask, the open downturned mouth giving us the primal agony of a father describing his daughter’s hideous death without making it cheap. He is a treasure.

Solid supporting work was done by Nikola Printz and Caroline Corrales as the victims’ mothers, Samuel Kidd as First Prison Guard (watch for these three singers as they add credits to their resumes), and Chad Shelton as a thoroughly charmless Father Grenville, the prison chaplain. The largest supporting role is the Warden sung by company stalwart Raymond Aceto, who seemingly took comedy lessons from Gilbert and Sullivan operettas and tried to transplant the approach into an opera that doesn’t support it.

After the curtain call, Jake Heggie was awarded the San Francisco Opera Medal for his contributions to the company and the city. He called the opera house a sacred space. It’s not an original way to conceive of a theatre, but it made me realize that his opera is a sacred act: a calling together, a calling in instead of a calling out. Heggie and McNally (and all the artists) gathered us around two grieving families, one broken man, and a woman of faith looking for the path to truth. An opera we know will end in death becomes the most life-affirming of experiences.