I don’t think I knew what opera even was, exactly, when my girlfriend bought us a subscription to the 2015 season in Santa Fe. We had moved there from New York more or less on impulse a few months ago, and we soon learned that there wasn’t much to do in town after dark. But, under the influence of youth and love, most anything was fun as long as we were doing it together, and, in that context, hiking up to the worst seats in the house on five consecutive Wednesdays sounded like a blast.

I got much more than I bargained for: that season, a Rigoletto (with Quinn Kelsey singing the title role) was transfixing, a strong sign that opera was going to be with me for life. And the Duke’s famous canzone that kicks off the third Act, “La donna è mobile,” made me realize I was already deeply familiar with a thin slice of the standard repertory—as music from the 2001 video game Grand Theft Auto III.

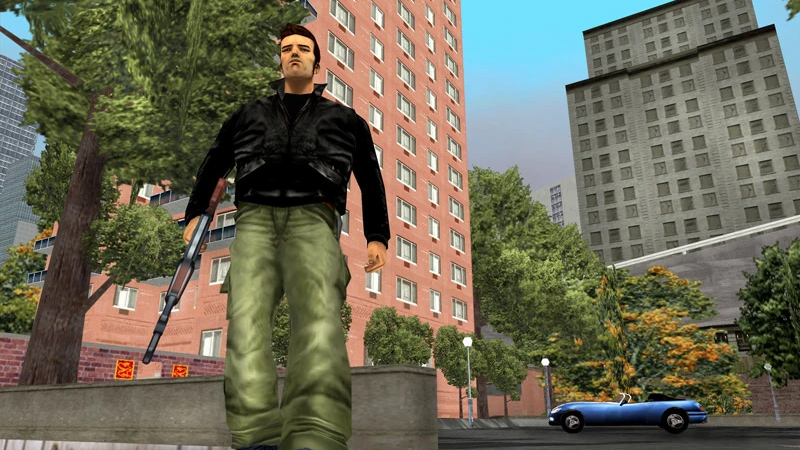

That game—revolutionary on release, one of the best-selling of all time—applied a novel “open world” freedom to a violent crime story you might find in a Michael Mann movie or a hardboiled crime novel. You controlled a mute career criminal who had just broken out of police custody and could freely navigate through a cartoon version of New York City. Even if it wasn’t central to the narrative, you were allowed to gun down bystanders, then solicit a sex worker, then kill that sex worker to get your money back, then steal that car. The game was wildly controversial at the time, and as a brace-faced pre-teen, I thought it was the greatest thing I had ever seen.

A big part of GTA III (as you might guess from the name) was driving around in hijacked vehicles, and I spent immense stretches of time cruising in ill-gotten Banshees and Sentinels. The game’s creators programmed hours of music that the player could control while behind the wheel, organized into radio stations, and one of those stations, “Double Clef FM,” was dedicated to opera. I could soon hum every tune. Some people were introduced to the art form listening to the Met’s NBC broadcasts on a glowing tube radio or watching acid-trip animated adaptations on the BBC or seeing Elmer Fudd sing, “Kill the Wabbit.” I came to opera through simulated drive-by shootings soundtracked by The Marriage of Figaro.

GTA’s thin budgets meant much of the soundtrack for the game was written and performed in-house, but the music team licensed real performances for Double Clef FM, doing an admirable job picking highlights: the obligatory Pavarotti, yes, but also Sesto Bruscantini following the baton of Zubin Mehta and Renata Scotto as Violetta and Lucia. The station also featured a DJ character, an annoying caricature of a classical music fan that would be trenchant if it were a little more precise.

I pieced all of this together later—some helpful soul has uploaded the audio to YouTube. Listening back to a soundtrack of my adolescent years, I was struck by how much of the music had flown over my head, that there was so much more meaning than I had been aware of as a young gamer. I had given up video games as waste of time at some point in college, and opera seemed to me to be somehow better than fodder for the Grand Theft Auto soundtrack; using beautiful singing like this as mere mood music to give a “mob” sort of feel seemed somehow degrading. And anyway, weren’t the great mafia movies soundtracked not with opera, but ersatz Italian folk music?

Meanwhile, I got deeper into opera, and I began to take note each time I heard a new Grand Theft Auto aria live. The next season, still in Santa Fe, I saw Don Giovanni, ticked off “Fin ch’han dal vino,” enjoyed the seduction duet and the catalogue aria even more, and generally had my mind blown. But I also experienced, for the first time, that fly in the ointment well-known to the jaded opera fan—that sense that what you’re seeing is inferior to a beloved recording. In my case, it was the inescapable sensation that the Don wasn’t quite as good as Nicolai Ghiaurov from the Playstation game.

A few weeks after the girlfriend and I moved back to New York, we went to the Met for the first time—fresh off of a cold desert night of Samuel Barber, taking in Rusalka or Rosenkavalier on a plush red velvet seat felt almost unspeakably luxurious. I checked off GTA arias in workmanlike revivals of Traviata and Figaro. We got married, put a Met gift card on our registry. We got a sense for what was going to be good—learned which composers and singers we particularly liked, which new productions were going to deliver. But it didn’t always have to be the best to be transporting: one Saturday in November, we rushed a sleepy matinee of Un ballo in maschera simply to have something to think about besides the baby we were expecting in eight days.

The rate at which I was collecting Grand Theft Auto arias started to decline. Mostly, this is because I discovered that the world of opera is bigger than the core of Italian repertoire to which Double Clef FM is dedicated. I still have one to go, the saccharine “O mio babbino caro”—someday I’ll either catch Gianni Schicchi, which seems to come back to the Met every ten years, or I’ll attend a tacky diva showcase. (The ditty was the encore of Anna Netrebko’s Palm Beach return to performing in the United States in February, but my invitation seems to have been lost in the mail.)

Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera

The last time I was able to cross a GTA aria off the list came at the Met’s most recent Lucia di Lammermoor. A co-production with the L.A. Opera, it was set — condescendingly, to some critics — deep in the contemporary criminal underworld of the American rust belt. I thought it was great. So much of the repertory depicts various kinds of warlords and goons, and it would be a shame if they were confined to the same vague, distant settings the original productions’ censors so often demanded.

This production brought the work much closer to the world of Grand Theft Auto. On the subway home, I began to reconsider: maybe the game and world of opera had more in common than I was able to see at first. The pleasures of the blood-soaked mad scene seemed to appeal to the same side of myself that once thrilled to temporarily inhabit a video-game thug. My supposedly intellectual love for opera had also meant many evenings of ruthless violence and cruelty. Operagoing requires a certain tolerance for depictions of retrograde attitudes from past centuries, and the slightly naughty pleasure I find in Don Giovanni’s sleaze or Scarpia’s fury suddenly seemed quite similar to my old enjoyment of the more unsavory aspects of Grand Theft Auto.

After all, GTA got raked over the coals by Australian censors and could only be released after extensive revisions—not so dissimilar from the treatment Rigoletto got from Austrian censors. There are plenty of dead sex workers on the Met stage every season, whether or not you want to count Mimì. And consider that the aria from Lucia included in the video game was the sextet that closes the second Act: those gorgeous harmonies are coming from a man who would sell his sister to the highest bidder and a few other knife-wielding toughs—gangsters, really. Could there even be a better soundtrack for a drive-by shooting?