Roberto Ricci

Though Parma usually presents its important Verdi productions at the festival in the fall, around the time of Verdi’s birthday, the Teatro Regio reserved an important new production for January, in the week before the anniversary of Verdi’s death: Giovanna d’Arco, handsomely staged by Emma Dante and sensitively conducted by Michele Gamba. Surely many of those present in Parma (including this reviewer) had never heard a live of performance of Giovanna d’Arco before, an early work from 1845, one year after Ernani, one year before Attila.

Yet, Verdi’s genius is fully present in this score, with an eerie conjuring of choral “voices” heard by the heroine, a rare Verdi mad scene for Giovanna whose sanity is undermined by those same voices, and a profoundly moving father-daughter baritone-soprano duet that anticipates the Verdian emotion of Rigoletto and Luisa Miller. There is, finally, a heart-breaking death scene for Giovanna, who does not burn at the stake in Verdi’s opera but dies on the battlefield (as in Schiller’s drama The Maid of Orleans). The libretto is by Temistocle Solera who had already prepared Nabucco and I Lombardi for Verdi.

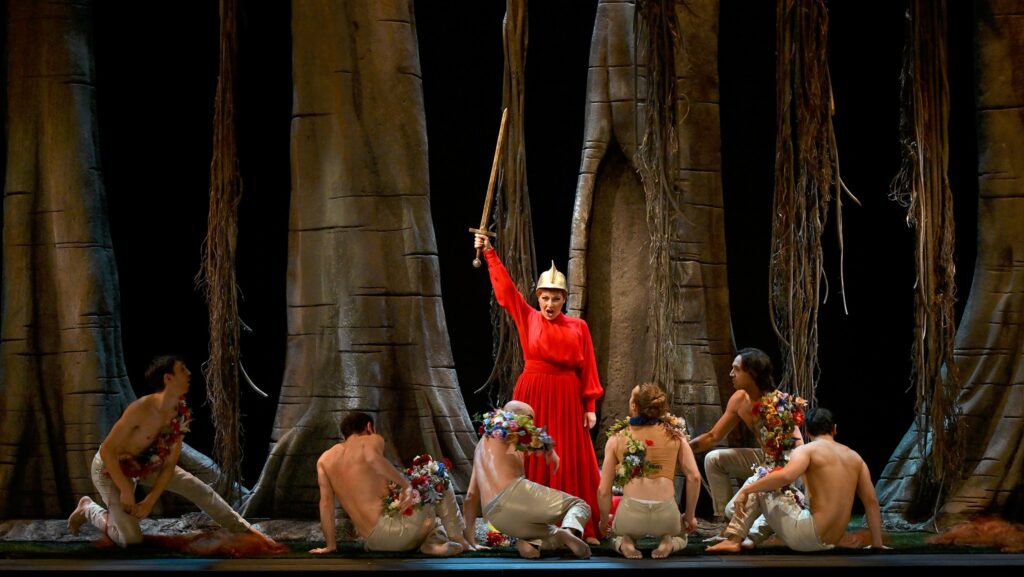

The Parma production of Giovanna d’Arco by Dante is simple and elegant: The forest grove where Giovanna hears her voices has arches festooned with flowers and dancers who seem to represent the pagan woodland spirits that infuse and confuse her sense of Christian piety. The coronation of the Dauphin as Charles VII, King of France, takes place in a chapel with golden columns among courtiers in stylized costumes of white and gold. The score was conducted by Gamba with the conviction that Giovanna d’Arco is a major Verdian masterpiece, tightly constructed around just three principal singers over some two hours of music. The Parma woodwinds were particularly expressive with individual instruments giving voice to Giovanna’s spiritual innocence, conviction, confusion, and self-doubt.

Roberto Ricci

Georgian soprano Nino Machaidze sang the title role with stunning commitment, and her many years of experience in Rossini and Donizetti roles served her well in Giovanna d’Arco, an opera that Verdi clearly composed with attention to the earlier bel canto tradition. Like Donizetti’s Lucia and Bellini’s Elvira in I Puritani, Giovanna has a mad scene or, indeed, several mad scenes, since, haunted by the voices that call on her to fight as a warrior, she is never quite certain of her sanity and also fearful that her piety has been compromised by demonic forces.

Verdi’s music of the forest already anticipates— with haunted tremolos and rapid descents in the higher woodwinds—the music for the witches in Macbeth. In the prologue there is a “coro dei demoni” (chorus of demons) that can be heard only by Giovanna, accompanied by triangle and harmonica, praising her beauty and questioning her sanity: “Tu sei bella/ pazzerella.” Verdi has a second “coro di angeli,” accompanied by harp, in pious counterpoint to the demons.

It is in response to the voices that Giovanna resolves to become a warrior and concludes the prologue in a frenzied duet with the Dauphin, based on four chromatically ascending syncopated notes, almost a dance rhythm of entranced delirium. In the first Act Giovanna, now at Reims, looks back wistfully at the “fateful forest” she has left behind (“O fatidica foresta”), and Machaidze sang the aria with exquisite delicacy, relishing the triplet ornamentation with flute obbligato. The Dauphin joins her for the cabaletta in which he declares his love and she confesses her fears, spinning out long beautiful lines of musical self-doubt and imminent madness, with the demonic voices returning at the conclusion of the Act.

Roberto Ricci

Machaidze was beautifully partnered by the young Roman tenor Luciano Ganci in the role of the Dauphin. He made his first appearance in the prologue in glittering armor, singing with golden tone and gleaming top notes. The opening aria belongs to him, Andante cantabile, in the despondent key of D-flat major, yet set to a lilting 6/8 rhythm over pizzicato strings, the recounting of a mysterious dream: “Sotto una quercia.” Under an oak tree in the forest he sees an image of the Virgin hailing him as king of France, the first intimation of the virgin Giovanna whom he will soon encounter under that oak tree. As the opera proceeds, and as Giovanna’s fragile psyche begins to give way, Carlo is the consoling voice in their duets, and Ganci’s tenor phrasings perfectly suited this role.

Machaidze has been a star since she sang as Gounod’s Juliette in 2008 at the Salzburg Festival, while Ganci, a rising star, was just singing Verdi’s Don Alvaro at La Scala in December 2024. They both sang superbly in Giovanna d’Arco, with a sense of drama that brought the unfamiliar opera to life on the stage, but the unexpected star of the evening was Mongolian baritone Ariunbaatar Ganbaatar in the role of Giovanna’s father Giacomo, at first enraged at his daughter’s unconventional course and then reconciled with her in a spirit of profound Verdian emotion.

Ganbaatar was not originally announced for this production, and when someone reported to me from the dress rehearsal that there was a great Mongolian baritone with a name that could not easily be recalled or pronounced, I immediately assumed it was Amartuvshin Enkhbat whose current international career received some of its impetus from early performances at the Parma Verdi Festival. In fact, it was Ganbaatar, a name unknown to me. Still in his thirties, he has been appearing in Russia and was making his first major Italian appearance in Giovanna d’Arco, singing with such idiomatic Italian phrasing, glorious tone, and emotional expressiveness that, like Enkhbat, he recalls the great idiomatic Italian baritones of past generations.

Roberto Ricci

The role of the tender Verdian father is perhaps first fully realized in the figure of Giacomo in Giovanna d’Arco. At the end of Act II Giovanna is arrested under suspicion of heresy, and the at the beginning of Act III she stands imprisoned in a golden cage, center stage, where her previously stern father finds her, finally with pity in his heart. She initiates their duet in ¾ time, in the key of B-minor, imploring his sympathy in aching phrases, “Amai ma solo un istante” (“I loved but only for an instant”) and he replies with transcendent emotion, shifting into B-major, “Ella innocente e pura!” (“She is innocent and pure!”). Machaidze and Ganbaatar traded phrases with the devastating beauty and pathos of consummate Italian Verdians, until her plea for his blessing took them into the thrilling cabaletta that they sang together in the A-major rapture of reconciliation. As the scene concludes he frees her from the golden cage and takes her place inside, so that she can take up arms to fight for France: a nicely conceived moment in Dante’s staging.

Roberto Ricci

Verdi’s operas, of course are all about giving voice to the most powerful emotions of men and women, and Giovanna d’Arco is no exception, but the story of Joan of Arc also concerns another category of voices: the mysterious voices that speak to the young woman who would centuries later be recognized as a saint. Verdi and Solera made those voices a part of the libretto and the score, a chorus of demons, represented on stage in Parma as pagan spirits of the forest. The supernatural voices of spirits are not regularly present in Verdi’s very human operas, but Don Carlo includes one heavenly soprano voice that calls out to the condemned heretics at the auto-da-fé to rise up to God and find peace.

It is not entirely clear whether Verdi intends this voice to be heard with irony, as with the entire scene of the auto-da-fé, but the music of the heavenly voice is so mesmerizing that it is tempting to believe that the heretics have been, in some sense, vindicated by God as victims of the Inquisition. While the heavenly voice is usually disembodied, sung invisibly from the hidden heights of the opera house, in Naples (in Claus Guth’s production revived at San Carlo in January 2025) the soprano actually walked across the stage at the conclusion of the auto-da-fé, robed in celestial blue as if she were the Virgin Mary, miraculously appearing to the faithful, like the dream of the Virgin under the oak tree in Giovanna d’Arco.

Almost fifty years after Giovanna d’Arco at La Scala in 1845, Verdi presented Falstaff at La Scala in 1893, on the threshold of the twentieth century. In the last act of Falstaff a troop of woodland spirits sing to Falstaff under an oak tree at midnight in the forest of Windsor; they are costumed as fairies and they denounce, mock, assault, and frighten Falstaff, until he realizes that they are only performing a drama, entrapping and punishing him for his presumption, all conceived as the revenge of the merry wives of Windsor. In the end, the spirits unmask and reveal themselves as ordinary humans, ultimately agreeing with Falstaff that we are all “tutti gabbati,” all of us fooled.

In Giovanna d’Arco in the 1840s the voices that haunted the heroine were either supernatural spirits or perhaps her inner demons, but, either way, they were serious forces that traumatized her fragile psyche and shaped her own vocal character within the opera. In Falstaff in the 1890s the demons and fairies were merely a farce, and Giorgio Strehler’s Goldonian production (revived at La Scala in January 2025) underlines the fact that the aging knight with his grey hair is living in a disenchanted world, free of supernatural forces. Verdi’s world itself was radically transformed from the age of bel canto and Romanticism in the 1840s to the fin-de-siecle modernity of the 1890s, but oak trees also live for a very long time, and the oak tree of Giovanna d’Arco could have been the same oak tree, fifty years later, presiding over the modern contrapuntal conclusion of Falstaff.

The first part of this two-part feature — discussing Falstaff in Milan and Don Carlo in Naples — is available here.