Brescia e Amisano

Every month is a Verdi month in Italy, but October is a special month for Verdian performance, especially in his native province of Parma where the annual Parma Verdi Festival coincides with the celebration of his birthday on 10 October (1813), while January is the month that culminates in the commemoration of his death in Milan on 27 January (1901), which also happens to be Mozart’s birthday. January 2025 began with the revival in Milan of Falstaff, Verdi’s most Mozartean work, his last opera and his only mature comedy, which had its premiere at La Scala in 1893, the year that Verdi turned eighty.

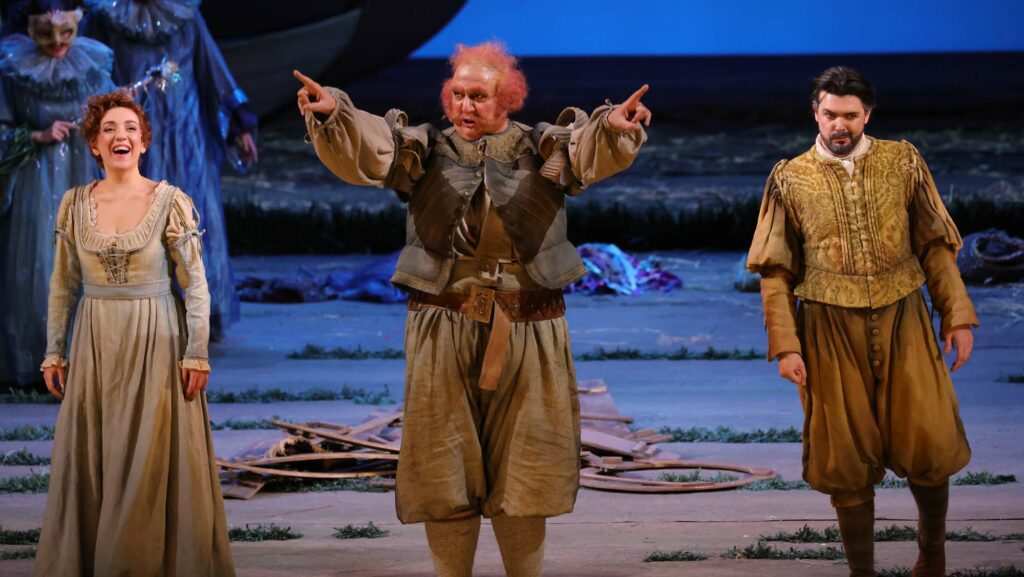

In January 2025 Falstaff was presented in a restaging of the classic 1980 production by Giorgio Strehler, one of the giants of twentieth-century Italian theater; he died in 1997 but his Falstaff production, after almost half a century, beautifully restaged by Marina Bianchi, remains a directorial masterpiece in an age when operatic direction often misfires with overly ambitious conceptual ammunition. A few days after La Scala presented Falstaff, the Teatro San Carlo in Naples revived its worthy (though uneven) recent production of Don Carlo, directed by Claus Guth, offering an emotionally traumatized Carlo, prostrate on the stage, who relives his psychic catastrophes in the course of the opera. Finally, the last week of January brought Parma’s brand new production of the early Verdi opera Giovanna d’Arco in a production by Emma Dante that magnificently made the case for the musical and dramatic power of this rarely performed work about Joan of Arc which I’ll discuss in detail in a separate post later this week.

Strehler’s production from 1980 was very quickly labeled as the “Falstaff padano”—set not at Windsor on the Thames but somewhere along the Adriatic delta of the Po River. Strehler himself was born in Adriatic Trieste and always had an affinity for the great Venetian dramatist (and librettist) Carlo Goldoni whose spirit is playfully present in this staging of Verdi’s final encounter with Shakespeare. When John Eliot Gardiner conducted Falstaff in Florence in 2021 he found elements of Renaissance music in the score, but Daniele Gatti at La Scala, perhaps partly inspired by Strehler, brought out the Mozartean dynamics of Verdi’s intricate ensembles.

In the Goldonian-Padanian Falstaff Nanetta and Fenton woo and flirt and twirl like commedia dell’arte figures; they also sing like angels, the only two non-Italians in the cast, Spanish Rosalia Cid and Argentine Juan Francisco Gatell. The lovers are styled as figures from the frescoes of Giandomenico Tiepolo (not his more famous father Giambattista), and the dramatis personae of the Ford family and friends who make up the great ensembles appear in a magical Adriatic light that alternately illuminates them and throws them into silhouette.

Italian soprano Rosa Feola, who not long ago was singing Nannetta, has now assumed the role of her mother Alice Ford, full-voiced with still the charm of youth and nostalgia for romance, singing with a radiance that suggested some spousal resemblance between Verdi’s Alice and Mozart’s Countess Almaviva. She was playing opposite the similarly youthful baritone Luca Micheletti as Ford; his jealousy was partly a matter of pride and possessiveness, but also suggested a husband infatuated with his own wife. With both Feola and Micheletti under forty, the Fords were by no means a stodgy and complacent bourgeois couple, but gave off sparks of youthful energy of their own.

Verdi’s first Falstaff in 1893 was the French baritone Victor Maurel, already a famous Don Giovanni, and it is not difficult to discern the almost parodic connection between these two operatic libertines, separated by a century: both trading on their nobility as a means of seduction, both outrageously confident of their own romantic and sexual charisma, both targeted and attacked by righteous and vindictive conspirators. Ambrogio Maestri has been singing the role of Falstaff for more than twenty years and, now in his fifties, has finally reached a plausible age appropriate to the part, while becoming over the years the opera world’s undeniable first Falstaff, larger than life, more charismatic than ridiculous, and marvelously philosophical.

Brescia e Amisano

When the curtain rises at La Scala he is seated stage center with one leg carelessly thrown over the arm of the chair and his richly commanding voice projecting steady calm while the other character perform their frenzy of antics all around him. Over the years, Maestri has become a master at finding the meaning in every word of Arrigo Boito’s libretto, singing with beautiful clarity. Falstaff has no arias, it is true, unless you count the thirty-second tribute to himself as a slender young page (“Quand’ero paggio”), but he has a series of monologues in which Verdi shows how perfectly he appreciated Shakespeare’s genius: There is Falstaff’s tribute to his own paunch, Maestri booming with regal authority “Quest’è il mio regno, lo ingrandirò” (“this is my kingdom, I will increase it”). There is his “honor” monologue in which he philosophically strips away every moral pretense of honor to show himself a profoundly nihilist libertine— reminding us that Maurel, who created the role at La Scala in 1893, had created the role of Verdi’s Iago at La Scala six years before.

Most magnificent of all, perhaps, was Maestri’s rendering of the “Mondo reo” (wicked world) monologue at the opening of the third Act, following the battering and humiliation of the second. Hauntingly he whispered the words— perfectly audible and comprehensible in acoustical space of La Scala— “ho dei peli grigi” (I have gray hair)— compelled for a moment to confront old age. But then he called for wine, and as it warmed him the audience could hear the growing warmth of Maestri’s voice, as he was stirred once more by the “trilling” of the world— which Gatti beautifully conveyed with the trilling of the orchestra. Marvelous was the moment, at the end of the third Act, when Falstaff reminded the triumphant conspirators that their lives would have no interest without someone like him to provoke them. Similarly, at the conclusion of the final fugue, the house lights went up, and Maestri gestured at the audience as he pronounced “Tutti gabbati”— everyone is fooled, meaning that life makes fools of us all.

Luciano Romano

This is comedy, and though Falstaff is deceived and humiliated he is clearly untraumatized at the end of the evening, but Don Carlo is tragedy, and Claus Guth’s production at San Carlo in Naples begins with Carlo completely traumatized, so that the opera can flash back through the stages of his collapse. A single chamber with a hexagonally patterned floor forms the basis of every scene, though the even more claustrophobic implication is that everything is happening in Carlo’s mind and memory. During the supremely great opening scene of the fourth Act, set in King Philip’s study, and including every major character in the opera except Carlo, Guth has the imprisoned Carlo present on stage in a lighted box alongside the study, as if he can witness or imagine his father’s drama. Reciprocally, during the second scene of the act, when Rodrigo comes to Carlo in prison, the audience still sees King Philip in his study, signing Rodrigo’s death warrant, so that father and son remain psychically connected.

Luciano Romano

Some of the details of the production are brilliantly conceived: During the gorgeous cello prelude to the study scene, we see not just the king’s desk but a convenient daybed from which Princess Eboli is collecting herself to depart after sex with the king. John Relyea gave a fine performance as Philip with a gravelly basso voice that plumbed the depths of the great fourth-Act aria “Ella giammai m’amò” (“she never loved me”), though the staging leaves one uncertain at first whether he means Eboli or Elisabetta. When the Grand Inquisitor then appears for the dramatic and disturbing basso-basso duet, Philip himself lies down on the daybed, and the Grand Inquisitor sits in a chair alongside the bed, as if, in Guth’s conception, he were the king’s psychoanalyst instead of his spiritual dictator, authorizing him to kill his son and commanding him to execute Rodrigo.

The production also has some conventional missteps, including the overuse (as in so many contemporary productions) of mime drama and video projections. Both mime and video are very tempting directorial gambits for opera, since they do not involve adding any sound to the musical score which remains absolutely inviolate. Guth introduces the mime role of a court jester who is constantly present on stage (actor Fabián Augusto Gómez) performing antics that act out, or perhaps parody, some of Carlo’s inner impulses. When Philip imagines his death and interment in the monastery of El Escorial, the jester places a paper crown on Carlo’s head as the heir; when Carlo and Elisabetta sing the stirring marziale duet about Flanders in the final scene, the jester is somehow present waving a banner.

Luciano Romano

Some audience members may feel that this silently enhances the drama; others may find it merely distracting from the dramatic power of the music itself. Video projections are also overworked: Guth accompanies Verdi’s beautiful tenor-baritone friendship duet between Carlo and Rodrigo with a video projection of two boys at play, the remembered childhood friendship of the two men. The same video of the same boys then recurs later in the opera, in automatic association, every time Verdi brings back the musical material of the friendship duet.

Italian tenor Piero Pretti sang with dramatic intensity and embraced Guth’s conception of a traumatized Carlo. American soprano Rachel Willis-Sørenson was in gorgeous voice as Elisabetta, her full and creamy soprano navigating the many facets of the role, from her tender farewell to her lady-in-waiting in the second Act to the sublime aria of feverish romantic renunciation that opens the final act. Guth has her wearing bridal white in the opening Fontainebleau scene but then Victorian black with a black veil at the Spanish court, where she sometimes just walks mournfully around the perimeter of the stage, evoking the image of another unfortunate Habsburg bride, Empress Elisabeth of Austria in the late nineteenth century.

Luciano Romano

Italian baritone Gabriele Viviani was in velvety voice as Rodrigo, and exceptionally moving in the prison scene that culminates in his death (accompanied by the sonorous Naples brasses under the baton of Hungarian maestro Henrik Nánási). Armenian mezzo-soprano Varduhi Abrahamyan was perfect for the sexy musical ornamentation of Eboli’s veil aria but somewhat disappointing in the opera’s most intensely dramatic aria, “O don fatale.”

While Relyea was powerfully effective as Philip, with the rumbling basso depths of an aging monarch, the supposedly ninety-year-old Grand Inquisitor was sung by the youthfully virile Ukrainian basso Alexander Tsymbalyuk, giving an unexpected combination of bass textures to their duet. The most youthful basso voice of all, however, impressively rich and beautiful, belonged to Georgian Georgi Manoshvili in the smaller role of the old monk who might or might not be the ghost of Emperor Charles V. Manoshvili, who sang the title role of Attila at the Parma Verdi Festival in 2024, is definitely somebody to watch for in the future. And our discussion will resume in Parma on Friday to discuss this season’s Giovanna d’Arco.