I get into the elevator with a six-and-a-half foot Oscar statuette. White-gold helmet hair. Gold Versace jumpsuit. Gold bling and protective designer sunglasses. He dwarfs me and the guy he’s with. It’s obvious that this is Haus of Shmizzay, the opera provocateur and influencer, and the reason I’ve come here to OPERA America’s National Opera Center for a conversation about the art of bel canto singing and the current state of voice teaching.

The event is sponsored by the enterprising Bel Canto Boot Camp (BCBC), which began as a Facebook practice group born out of desperation in March 2020, and grew to an online community of more than 1700 singers, voice teachers, coaches, and conductors, all working together posting practice videos and sharing progress. BCBC, which received its name from parterre box publisher and old-school singing aficionado Nick Scholl, is now a vigorous 501(C)(3) determined to teach performers and audience members about old-school technical methods and true artistry in operatic singing.

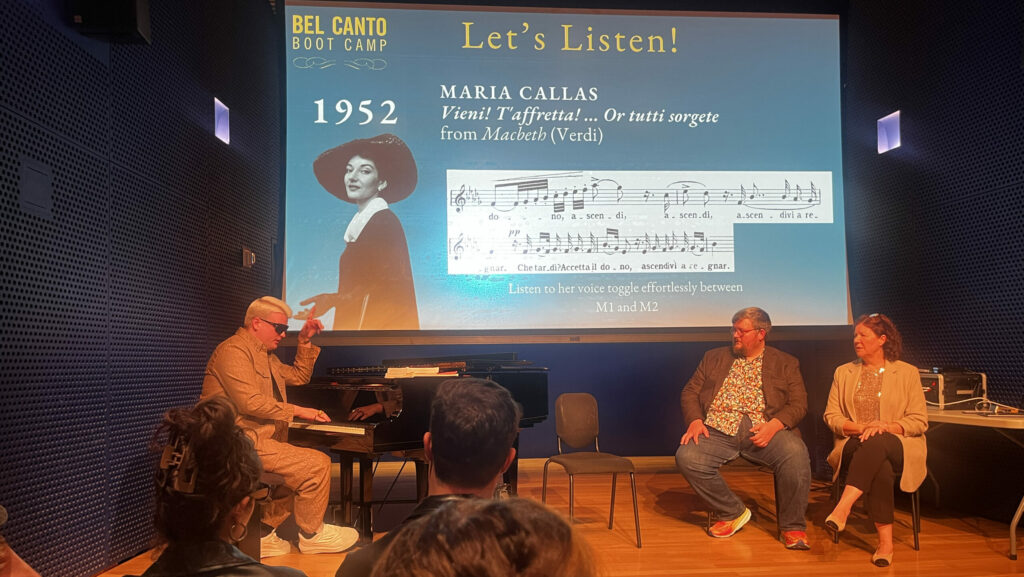

The point of tonight’s session is to kick off a series of presentations where vocal coaches Rachelle Jonck and Derrick Goff, the masterminds of Bel Canto Boot Camp, will chat with teachers, coaches, conductors, and others who share the core values of BCBC. Haus of Shmizzay, whose real name is James Smidt, is a kind of prelude to nine sessions planned as “Spring Training Tuesdays” at OPERA America from February to April 2025. Conductor and vocal historian Will Crutchfield, tenor and voice teacher Jack Livigni, and coaches Michal Biel, Katelan Terrell, and Ksenia Leletkina are among those already engaged, while past BCBC guests have included Michael Spyres, Jack Swanson, and Lisette Oropesa.

James is currently the hot voice teacher in New York. His in-person and online calendar are full. Students fly in from Germany to work with him. His rogue Instagram presence came onto my radar last year, and I loved his audio posts comparing dead sopranos with current working gals in choice aria moments. In an interview with Opera Innovation, James admitted to taking time off in 2019 to rethink his own lackluster performing career. He was giving lessons to friends during COVID lockdowns, began a voice teaching Instagram, then discovered memes. He jumped into the OPERA America listserv transphobic email scandal and gained even more attention.

His day job was at a large, well-known private equity firm. “It turned out to be a perfect fit for me because, essentially, I was a glorified houseplant. My daily routine involved sitting at a desk, answering just two phone calls a day, sending three emails, sipping coffee, and building my Instagram presence. It provided a full-time salary for what was essentially spending time building my Instagram world, which set me up perfectly for the transition into teaching.” He is still amazed at how everything took off, and his studio is now booking months in advance, with more than half the students actively singing in top opera houses and major Young Artist programs.

Tonight’s session includes plenty of demonstrations, audience participation, laughter, and guided listening. BCBC had arranged topics in PowerPoint and began by outlining their initiatives. These include sharing resources–including historical treatises, vocalizes, Italian poetry rules, libretto translation guidelines, and more—on their website, and a book that grew out of the lockdown practice sessions.

The Vaccai Project: A practice diary exploring the historically informed performance practice of the bel canto style inspired by the classic lessons of Vaccai is a 280-page compendium of historical material, exercises, and inspiration, including journal prompts and a clean new edition of Vaccai’s instructional songs, in a structured workbook format with a friendly and supportive tone. Italian librettos are dissected, registration exercises (balancing head voice and chest voice) are numerous, QR codes link to videos, and instructions are given for reducing a piece to its musical skeleton in order to understand the composer’s, as well as one’s own, ornaments. (Full disclosure: I have participated from the beginning as a singer, voice teacher, audience member, and sometime critic, and make heavy use of the website and the book in my own work.)

Audience development and outreach are special passions of Rachelle and Derek, who travel around the US, Europe, and South Africa to teach, and are particularly interested in the opera loving community that lacks listening tools to discriminate and hear through the hype. Tenor and audiophile Steven Tharp joined BCBC to present Sunday afternoon listening sessions over Zoom, where a lively chat commentary holds nothing back. Steven has been listening to old singers for years, and curates sessions often themed by nationality or repertoire that go far beyond the usual golden age stars. But above all, BCBC is ruled by the collaborative, service-oriented spirit of ubuntu, a term from Rachelle’s South African homeland that means “I am because we are.” “When you join Bel Canto Boot Camp and its projects,” the website clarifies, “you do more than enter our shared, safe, creative space: you enter into the spirit of ubuntu.”

Is this zeal from both BCBC and Haus really necessary? How bad is the current state of singing? And when did it begin to deteriorate? You might blame the microphone and the recording industry, which promoted small-voiced singers with personality, or stage directors and video productions that demanded physical attractiveness at the expense of vocal excellence. Glamour master classes or taking a voice lesson only once a week, rather than seeing a teacher every day, might have contributed. Maybe larger acoustically-unfriendly performance spaces are to blame, or bigger orchestras, or the gradual rise in pitch. Maybe the fault is singing heavy repertoire too soon, or singing a greater variety of repertoire, or singing too often, or taking jet planes instead of ocean liners when the singer could work with the conductor for several days on board.

Or maybe it’s changing aesthetics, but does anyone really prefer wobbly vibratos to a gorgeous chiaroscuro sound? Many university voice programs prioritize volume and brightness over expression. Students also have to satisfy requirements in diction, movement, theory, history, and other academic classes that eat into practice time. But is conservatory voice teaching itself at a consistently high level?

The meat of the OPERA America session involves defining the principles of bel canto singing, shared by both BCBC and Haus, and trying out some exercises. (A roomful of opera singers is LOUD.) James emphasizes the connection between speaking and singing, and a recording of William Butler Yeats reading his poem “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” displays vibrato, trills, a reciting tone, and variety of speed and dynamics in a quasi-sung delivery. It’s a fun way to awaken our listening skills.

During the session much attention is paid to “the glottal onset” described by the OG voice teacher, Manuel Garcia II (1805 – 1906; yes, you read that right), and we all practice calling across the room “Eh!” like Italians in the piazza. As part of an illustrious family that included his father Manuel Garcia (Rossini’s first Almaviva), Maria Malibran, and Pauline Viardot, he must have been delighted when his invention of the laryngoscope in 1854 proved everything he had been teaching about singing was right.

In addition to this “coup de glotte,” Haus and BCBC emphasized minimal effort, organic processing, legato, well-developed chest voice, and portamento, how to get from one note to another without changing the sound. We use the video software program VoceVista to look at some coloratura passages from famous singers, our eyes confirming what our ears heard; some sing disconnected, pecky runs, while others glide through passagework with lovely legato.

We do some exercises switching from head voice to chest voice and back again and look at historical treatises describing and illustrating this. All the old exercise books begin with long notes and registration exercises, saving scales and arpeggios for much later. We listen to examples of perfect registration from Sigrid Onegin, Louise Homer, and Claudia Muzio, as well as some recordings where the dramatic situation calls for chest voice much higher than the bel-canto-prescribed F. (Think Lucia’s “il fantasma,” Santuzza’s “Io piango,” etc.) Rachelle finds several places in the repertoire for what she calls the “achey-brakey voice,” the slightly sobbing “Sicilian widow” sound, and we attempt this also.

She expands on this later: “Singers are routinely asked by conductors, coaches, and yes, teachers, to omit the audible portamento in cantabile music, insert h’s in their coloratura, avoid chest voice up to F4 — the F above middle C. These instructions,” Rachelle elaborates, “are clearly the very opposite of what singers were taught up to roughly 1940 as evidenced in recordings of the late 19th and early 20th century and described extensively in treatises of the 19th century and before. It also happens to be how the voice functions naturally.”

One current popular notion is that chest voice is to be avoided entirely, which really bothers Rachelle. She is passionate about this fundamental technical skill. “Sadly, it is the portamento and the chest voice above everything else that carries the soul of the voice to the ear of the audience, and people who are against this are robbing singers of their expressive voices and robbing audiences of hearing them. If you think this is ‘the new style of singing,’” she asks, “then why not have ‘new style opera houses’ where people can sing non-legato, whisper, shout, and explore expanded vocal techniques? Use a microphone if you feel like it, since that’s what inspired these new ways of singing.”

The session also includes plenty of talk about voice science and the current state of voice teaching. Many college programs are run by voice scientists disguised as pedagogues, and an emphasis on mechanics, in the nature of formants, the cricothyroid and thyroarytenoid muscles, semi-occluding the vocal tract, or singing through a straw – all jargony terms for which I have no time.

BCBC might use VoceVista’s analytic information to back up what they hear with their own ears, but Haus dismisses it outright. In his Opera Innovation interview, he admitted that “at the conservatory level, I experienced a kind of almost anti-old-world pedagogy, and everybody was so concerned with the science, spectrographs, muscle functions, and allegory. It would be like going to art school to learn how to paint, and rather than learning how to paint, you’re expected to learn, diagram and label all the muscles of the hand and do mathematical calculations on color theory, instead of just picking up a freaking paintbrush and learning the strokes!”

BCBC’s Derrick Goff also places voice science firmly in the university setting and considers it another way to take money from singers: “As a non-built instrument, we can keep creating hypotheses and try to prove or disprove them. What is not taken into account is that the voices that are studied scientifically are often not the best ones, and often not working at the maximum efficiency. A lot more study of defective voices happens than great ones.”

Will Crutchfield, the BCBC-adjacent vocal historian and conductor, agrees. “Given that singing reached peak levels of achievement when ‘voice science’ didn’t exist, it can’t be considered necessary. I think it can be helpful if it’s used to organize the information our ears already tell us. But overall, I think it’s more useful for criticism and history than for learning how to sing or how to teach.”

Rachelle thinks “science” is the key word. “It seems to me that voice science seeks to bring order to the chaos of modern voice teaching, which in turn feeds that ‘touchy feely’ world of personality cult teaching that has dominated for the past 75 years.” Of course, old-school teachers were also interested in anatomy (remember Garcia dropping a small mirror down his throat?), but BCBC and Haus seem to agree that the ears are the most important tool. Clearly voice scientists need to be studying great singing and not just five random singers going into a studio to record the C above middle C on various vowels.

And yet, technology has been useful in tracing the increasing slowness of singers’ vibratos. Crutchfield points out that “the average rate has fallen from about 6.7 cycles per second to about 5.5. And vibrato on high notes used to be same-or-faster compared to the rest of the voice, while now they are same-or-slower. So, science is helpful there, because it can give us a fact in place of a suspicion, and that might provide a spur to action.”

He insists that “sluggish vibrato” goes hand in hand with “off-the-voice piano,” “darkened vowels,” “underdevelopment of chest voice,” “scooping into the pitch,” and “unintended local diminuendos” as general markers of a move from greater to lesser laryngeal energization. It’s only a slight oversimplification of that to qualify it as “a move away from opera singing and towards laid-back mic singing.” Sounds disturbingly like Rachelle’s “new style opera house.”

The OPERA America session made clear that both Haus and BCBC are trying to bring back the musical and aesthetic values of the past. Complaining about wobbly sopranos currently singing at the Met is one thing but, as Derrick pointed out, this year at the Met competition all the women used chest voice properly and there was no choppy coloratura. But does this represent the current state of vocal training? The taste of the judges this year? Or is it just random?

These are passionate, driven artists and they are preaching to my choir. They are on a mission, and they want to educate the listening public. Haus can be both endearing – in his pride that his students are “making efforts toward returning theatrical Italianate singing to the center of the operatic aesthetic in the 21st century” – and delightfully obnoxious – “my brand is unapologetic, it is uncompromising, it is convicted, it is unmistakable, and it is CONTROVERSIAL because it is AUTHENTIC.” He goes on, “I refuse to make art on someone else’s terms.”

But to ensure a future for solid artistry, developing a public capable of listening critically is the fundamental other side of this equation. “The single most important task towards achieving great singing,” Rachelle points out, “is bringing together people in discussion and exploration of the essence of great singing. We are living in a world where singers are singing on our largest stages with basic technical deficiencies because they have not been rigorously instructed. And as a result, the standards to which they are held in our industry are ever being lowered. It is time to raise the bar and renew our commitment to excellence.”

Photos: Courtesy of Rachelle Jonck/Bel Canto Boot Camp