As I missed La Monnaie’s Siegfried because I was still sunbathing in Greece, and Paris’s Butterfly because I couldn’t be bothered, my new season starts with three new works – new to me at any rate. Later this week, at the Opéra Comique, I’ll discover George Benjamin’s Picture a Day Like This. Later this year, Mikael Karlsson’s Fanny and Alexander. But I begin in Brussels, with Kris Defoort’s The Time of our Singing based on a 2003 novel by Richard Powers. This premiered, post-Covid, in 2021 and won the Best World Premiere prize at the 2022 International Opera Awards.

If you know the book, you can skip this plot summary and go to the next paragraph: David Strom, a refugee German Jewish physicist, and Delia Daley meet at Marian Anderson’s performance at the Lincoln Memorial in 1939. United by their love of music, they marry and have three children: Jonah, a tenor, Joey, a pianist, and Ruth, an activist who joins the Black Panthers and loses her partner to police violence. In three acts and twenty tableaux, the opera (like the book, only here, to simplify things, chronologically) chronicles their lives and the issues they deal with. As La Monnaie’s website puts it, ‘the main characters’ search for their identities intersects the trajectory of the African American Civil Rights Movement. Six crucial, historical events take place around them, are discussed or intervene in their lives. These events: Marian Anderson’s concert; the Harlem riot of 1943;, the march on Washington twenty years later, the Watts riots; the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr.; and finally the LA riots of 1992, punctuate the work forcefully.

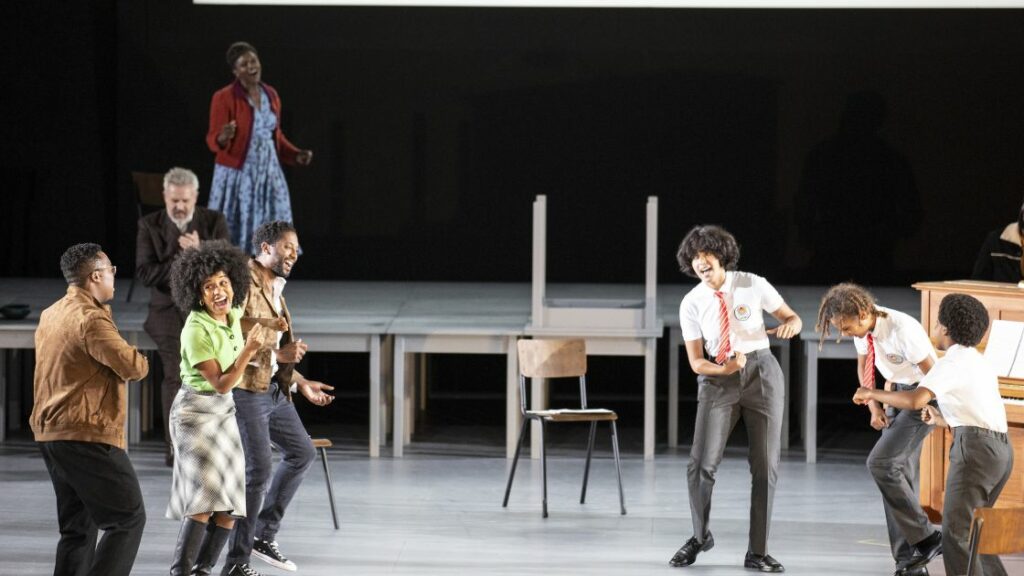

Ted Huffman’s production avoids bombast. It is simple but ingenious, delicate and sensitive, and the acting is remarkably natural, as if you’re watching ordinary people on stage, who just happen to be singing. There’s only one set, a large rehearsal room with a rectangular central space surrounded by massed, square tables, forming a platform, an upright piano (in addition to two grands in the pit) and the odd chair. The characters stay on stage, whether involved in the action or not. They stand beside or sit on the tables, pull props out from under them, and change their timeless, mid-century clothes in view. Newsreel footage, progressing over time from black and white to colour, is projected at the rear and on props. When riots erupt, the tables are overturned violently, with a series of ear-splitting cracks.

The scoring is for chamber orchestra – with, like many of today’s scores, plenty of burbling and tinkling percussion – and a jazz ensemble centred on an impressively virtuoso saxophone part (recalling, irrelevantly, Einstein on the Beach). It is kaleidoscopically eclectic, seamlessly knitting together musical idioms: the chamber orchestra supports the jazz musicians, the jazz musicians join in quoting the classics quoted, I believe, in the novel: Purcell, Schubert, a send-up of ‘Nessun Dorma.” The work alternates between spoken dsalogue and song, and when singing, characters are assigned distinctive styles, noticeable but not simplistically systematic: bluesy for Delia, classical for Jonah, loud R&B with (what sounded to my uneducated ear) like Marvin Gaye undertones for Ruth, a brief, wild coloratura number for Lisette.

Perhaps to match the cool, understated way the work treats (more than confronts) the personal issues it raises, the central trio — Delia, David and Jonah — is cast with modest-sized, lyric voices (i.e. not hectoring, Wagnerian blunderbusses). The orchestral writing is no more challenging than Britten’s Death in Venice or Curlew River, which were probably brought to my mind by the percussion. The overall sense I got was not so much one of discernible thematic development – to me, the score felt relatively fragmented – but of marking the passage of time and events through its twenty distinct tableaux.

The stars of the show, on Sunday, were (not unexpectedly, as their roles are central) Claron McFadden, Simon Bailey, and Levy Sekgapane. I had lost sight of Claron McFadden since her Rameau days under William Christie, but she’s come through the years apparently unscathed; her voice is still clear, crisp, lyrical and moving. Simon Bailey’s bass-baritone is equally lyrical, light yet firm, elegant in an English-sounding way (there was, by the way, no attempt in this production to fake American accents – each used his or her own voice; this didn’t bother me but annoyed some people around me). And Levy Sekgapane, who I see sings quite a lot of Rossini, is, again, an agreeably lyrical tenor who would be a pleasure to hear again.

This may all sound much of a tepid muchness, but not at all; the ‘reasonable’ singing style, also deployed by Peter Brathwaite as Joey, the hesitant brother, matched the natural, matter-of-fact acting. As William Daley, Mark S. Doss was suitably bluffer and gruffer, and, though her extravagant number is short, Lilly Jørstad carried it off with lasting impact. Abigail Abraham, whose career goes beyond the operatic stage into film, TV and musicals, has received unanimous praise from the press for her vehemence as the militant sister Ruth. I personally found her less convincing, vocally, and less real, dramatically, than the rest of the cast, but perhaps I’d just made the wrong choices at lunch. Kwamé Ryan was visibly engaged and attentive in the pit, though I had a feeling La Monnaie’s chamber orchestra wasn’t always exactly on the ball, especially at the start. (OK, it’s hard to judge, on the first hearing of a new score.)

‘The bird and the fish may fall in love but where will they build their nest?’ asks Powers in the novel. This opera raises the issues worked through by three generations of a mixed-race family, including the wrenching question of identity faced by the children, potentially rejected as neither fish nor fowl. It does this against a background of ongoing racial tension and sometimes violent struggles, without, as I hope I’ve implied, facile tubthumping. In today’s febrile context, the impact of those explosions of violence, supported by newsreels, is hugely forceful, even harrowing. You could see it on people’s faces as they emerged after the first two acts.

But does the harsh reality of the historical facts inevitably tend to crush or crowd out the individual and family issues? Then, after so much harrowing reality in Acts I and II, the discovery of Ruth’s school work, teaching underprivileged children to sing (at La Monnaie, this involved a real children’s chorus, Equinox, that is part of a similar, real-life social project supported by pianist Maria João Pires ) had a faintly fabricated feel-good-feel to it, verging on ‘eau de rose.’ The dénouement of Jonah’s death, hit by a stone while witnessing a riot, also rang a touch less true. But these are perhaps weaknesses transferred from the novel to the opera. The last act might benefit from some tightening-up to preserve the work’s dramatic truth over the full, three-hour duration.

The plot also raises questions of artistic choice and freedom in the fictional family that extend uncomfortably beyond the fourth wall into our real world. Kris Defoort insists that artists have the right to deal with any subject. I agree. But obviously, as you sit there in a Belgian opera house on a Sunday afternoon, surrounded by the mainly white middle classes, digesting lunch and listening to a work by a Belgian composer that plots 90 years of America’s bitter racial struggles onstage, various rather troubling interrogations run through your mind. I read, indeed, that one of the co-producers of The Time of our Singing pulled out before the premiere, having decided that the production team was just too white. As a European spectator of an opera based on an American novel, dealing in part with events in recent US history, I cannot capture in a single sitting all the nuances of what the piece brings to a contemporary conversation. It would be a brave — I hope not foolhardy — and worthy initiative by a US house to find out by scheduling it.

Photos: Hugo Segers and Bernd Uhlig