Washington National Opera’s season opened this past weekend with a new production of Beethoven’s Fidelio directed by Artistic Director Francesca Zambello and featuring Robert Spano, WNO’s new Music Director designate, in his first appearance with the company since his appointment earlier this year.

If Zambello’s season-ending Turandot last year represented some of the best of what WNO can offer in the standard rep, this Fidelio was a regression to the mean, with some laudable musical values pit against an unfocused production.

Zambello’s most extensive intervention came at the top of the show, with an elaborate pantomime played out over the overture. While the band toiled away, the audience was focused on untangling a series of tableaus from Florestan’s life as an activist and home life with Leonore, as narrated by a series of faux newspaper clippings on the scrim.

This was a down payment on the production’s bigger goal of grafting Fidelio’s story about personal persecution onto a modern political prisoner narrative, with Florestan recast as the enemy of a repressive 20th century regime. Stealth edits to the libretto (I assume these were just changes to the supertitles since there was no new dialogue credit), as well as a vague updating to 1940s Europe, reinforced this scenario.

It’s easy to see the appeal of applying this lens to Fidelio; while the opera’s big themes of repression and liberation are well-suited to current audiences, key elements of the story (family-run jail, petty noblemen, etc.) read as decidely quaint. Unfortunately, this production’s busy efforts to bridge that gap through tinkering with the exposition felt like a thin substitute for providing real insight into either the original work or a time period closer to our own.

Pizarro’s arrival and his aria “Ha! welch’ ein Augenblick!” were taken at the beginning of the first Act here, introducing Australian bass-baritone Derek Welton, who specializes in Wagner roles in the biggest houses in Germany but has few North American credits to date. Welton brought a serviceable snarl to Pizarro but didn’t quite have the bite or presence in the lower reaches to make a strong impression vocally.

Soprano Tiffany Choe, a current member of the WNO young artist program, had a winning turn in Marzelline’s aria, deploying her sparkling soprano with a beguiling mix of fluttery charm and heartfelt yearning that lent unexpected emotional weight to the ingenue’s lament. Her Jaquino, Sahel Salam, was a game partner in the young lovers’ material and his pleasing tenor made a fine contribution to the ensembles.

The unique depth and coloring of David Leigh’s bass supplied a memorable sound for Rocco, though his repeated coordination problems with the pit interfered with both solo and ensemble passages. While Leigh’s portrayal captured appropriate notes of tenderness and moral negotiation for Rocco, a lack of effort to differentiate him age-wise from the rest of the cast hampered his ability to project much fatherly authority.

The Irish soprano Sinead Campbell Wallace, another singer infrequently heard on these shores making her WNO debut, was a compelling Leonore. Her urgent, forward sound was a good fit for the character’s pluck and resolve, with a powerful, shining upper register brought to bear in Leonore’s climactic moments. Those elements made for a number of exciting moments in her opening night “Abscheulicher!” though deliberate pacing from the pit and a sense of caution in the transitions limited the ultimate impact here.

Act II opened on tenor Jamez McCorkle spinning an epic dynamic effect out of Florestan’s cry of “Gott,” the first in a series of skillfully executed pieces of phrasing in a reading that prioritized delicacy and precision over sheer force. McCorkle’s honeyed tenor had an inviting lightness not usually heard in this music, though the tradeoff was in reduced cutting power against the biggest orchestra swells in Florestan’s solo section or an otherwise very exciting “O namenlose freude!” duet with Wallace.

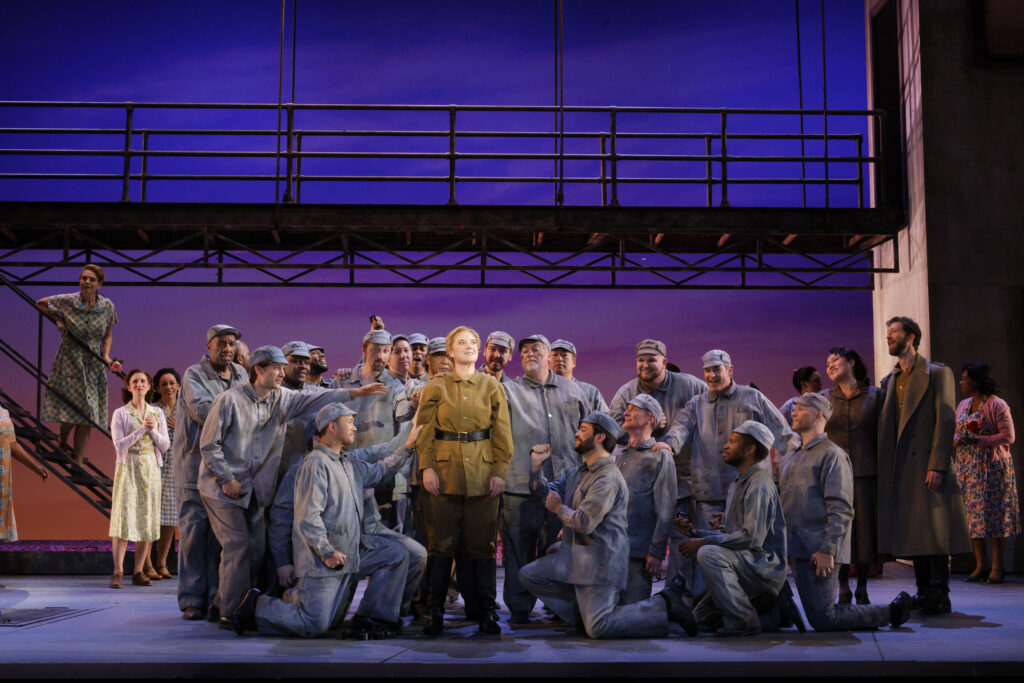

In a twist for the finale, veteran mezzo-soprano and frequent WNO contributor Denyce Graves took on the role of minister Don Fernando. (Under this production’s constitutional scenario, she is actually called the “Prime Minister,” who has been reinstalled after the fall of the regime which occurred just in time to save Florestan. Yes, this will be on the quiz.) Arriving on the catwalk in a stunning white pant suit number, Graves’s command of the stage and vocal magnetism pulled off the rare feat of making Fidelio’s predictable deus ex machina feel like an event.

Robert Spano set a restrained and unshowy tone in his debut on the podium. Considered pacing and a sensitive approach to the singers allowed passages like the great Act I quartet to unfold with a natural ease and inner propulsion. While the overture and some of the tension-building material in Act I might have benefited from a stronger hand and sense of surprise, Act II felt thoroughly locked in, and Spano presided over a boisterous finale. The chorus, prepared by Steven Gathman, did much to contribute to that exciting finish, redeeming a murkier impression left after the Act I men’s chorus.

Zambello stated in the director’s note that she has opted for a “spartan visual production” here, and indeed, as with many Fidelio productions, this was a bit of a drag to look at. Sets by Erhard Rom featured a simple catwalk and staircase with a few elements like a barbed wire fence and office wall flown in–just enough set to look underwhelming, but too much to look like there’s any sort of deliberate minimalist perspective in play. The costumes (Anita Yavitch) did the heavy lifting to suggest mid-century Europe, but the guard outfits leaned too heavily into recognizable World War II-era German visual cues for a fictional world that never intended to address such weighty imagery. Lighting by Jane Cox effectively captured the transition from bleak prison yard to sunny resolution.

Photos: Cory Weaver