Lodovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso stands as a towering masterpiece of Italian literature, with its tapestry of fantastical characters and its rollicking medieval universe inspiring a breadth of later works in literature, visual art, and music. One of this sensuous epic poem’s central narratives depicts the liberation of the Saracen knight Ruggiero from the sorceress Alcina’s enchanted island—a dramatic subject that captivated composers of opera like Georg Frideric Händel, Riccardo Broschi, and Francesca Caccini.

Caccini’s La Liberazione di Ruggiero dall’Isola d’Alcina (1625), believed to be the first opera composed by a woman, presents this facet of Ariosto’s romance as a power play between the virtuous Melissa and the seductress Alcina as they battle for Ruggiero’s soul. The opera’s forward-looking emphasis on feminine agency can be credited to the Archduchess Maria Maddalena of the Medici court, whose patronage supported Caccini’s gifts for composing dramas around empowered female protagonists.

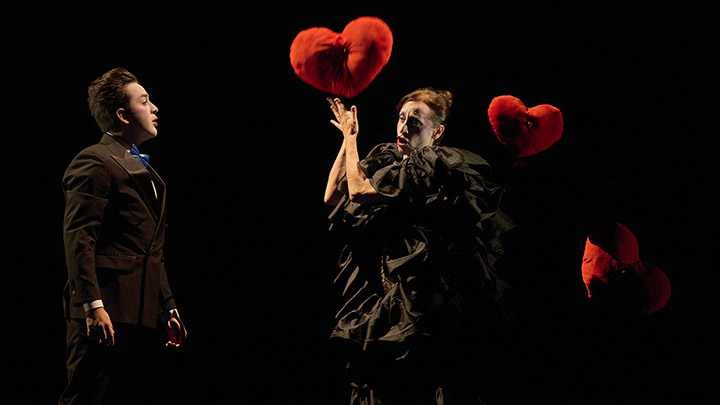

Recently, Caccini’s sole surviving opera made its long-awaited Spanish debut through a collaboration between the Teatro Real and the Teatros del Canal. Eschewing the opulence characteristic of baroque theater, Madrid’s new production—conceived by choreographer Blanca Li in tandem with lighting director Pascal Laajili and costume designer Juana Martín—deftly integrated character direction with a minimalist backdrop of flowing fabrics, striking illuminations, and evocative costumes. Complemented by expressive dance sequences, these elements coalesced to underscore the modern sensibilities of Caccini’s powerful sorceresses. Blanca Li’s dancers played an indispensable role in animating the fantastical realm of Alcina’s enchanted island, their movements breathing life into the magical creatures and reflecting the ever-shifting moods of the supernatural beings that inhabited this realm, transforming the stage into a vivid tapestry of symbols and puppetry.

While Caccini’s score may lack the dramatic pathos or the musical ingenuity of Händel’s renowned masterpiece, its brisk one-and-a-half-hour runtime offers lilting entertainment and, more importantly, a window into a unique historical moment for women in music.

Francesca Caccini’s balletto in musica embraces the recitative-driven forms developed by Claudio Monteverdi and Jacopo Peri during opera’s nascency. While much of the score’s ritornelli and balleti are beautifully orchestrated, Caccini’s vocal writing oftentimes settles into the realm of the unmemorable and stylistically homogeneous. During moments of inspiration, Melissa and Alcina can dominate the stage with stretches of expressive music, but seldom do the melodic variation or the text transcend mere superficiality. Absent are the sublime heights and cathartic depths that suffuse the great moments of Monteverdi’s Poppea. Nor does this Alcina rend audiences with the gravitas of her Handelian counterpart when her powers ultimately crumble.

However, a work that skimps on profundity need not be devoid of entertainment value, and Madrid’s charismatic soloists and musicians more than capably deliver on this front. In the pit, the Asturian conductor Aarón Zapico, leading his excellent period ensemble Forma Antiqva alongside players from the Teatro Real, performed Caccini’s orchestration with a dancelike vibrancy and exacted exquisite blending from his pit and onstage musicians. Zapico and his soloists consistently demonstrated command over the composer’s stylistic ethos through accompaniments that are exquisitely timed to the libretto’s brisk patter, evincing a cohesion that belies the 17th century score’s lack of markings and structural formalities. Zapico’s brothers Pablo (lute) and Daniel (theorbo) and the winds of the Teatro Real’s orchestra deserve special mention for punctuating and enlivening the score with flavor and variety.

Among the main cast, Vivica Genaux exudes imagination and heroism as the benevolent sorceress Melissa, with her smoky instrument and striking stage presence lending credibility to her role as the narrative’s moral force. If Caccini painted her idealization of Alcina as a whimsical character easily played for caricature, the Spanish mezzo soprano Lidia Vinyes-Curtis nevertheless evolves a fascinating portrayal that dwells on the character’s obsessive attachment to Ruggiero despite her writing’s dearth of eros. When Vinyes-Curtis takes center stage for her climactic mad scene, the mezzo’s commitment to an approach that intersperses formal operatic singing with raw, direct vocalizations proves especially effective. Finally, although Ruggiero’s part is minor relative to the opera’s sopranos, the Spanish tenor Alberto Robert deserves plaudits for the beauty and ease with which his lyric tenor evenly scales his vocal lines.

Blanca Li’s dark and minimalist production, with its judicious use of fabric and vibrant floating phantasmagorias, may not overtly evoke the fantastical symbolism or the visual sumptuousness of Alcina’s enchanted island. However, Li’s understated concept masterfully directs the audience’s gaze toward the electrifying power play between Genaux and Vinyes-Curtis, as they vie for the entranced Ruggiero’s allegiance. While Caccini’s work might lack overt pathos or sharp focus, the musicians’ and singers’ unwavering commitment to imbuing theatricality and buoyancy into this affair elevates it to a cultural event of profound significance, resonating with contemporary themes of feminine power and resilience.

Photos: Pablo Lorente