In the Dvorák Requiem, set to classical Latin liturgical texts, the sinners fall in line, while the titular libertine of Mozart’s Don Giovanni is defiantly unrepentant and falls into the fiery pit.

The Dvorák Requiem was composed in 1890 and performed for the first time on October 9, 1891 at a choral festival in Birmingham, England, with the composer conducting. Having heard the Verdi Requiem just a few months ago with the same soprano soloist, I cannot help but compare the two works, which share many identical texts. Verdi’s is more dramatic with audible fire and brimstone in his setting – his soloists are more abject in their pleas for absolution. Dvorák’s is more of a spiritual journey of the soul with the individual confronting his own mortality – it is lyrical and is a journey toward peace and spiritual wholeness. The program describes the work thus:

“While rich in invention and expressivity, it is its tender, melancholic examination of the mysteries of life and death that ultimately make this requiem so deserving of further exploration in the public sphere—far more than it has received up to now.”

The Dvorák setting has great melodic beauty, a beautiful orchestration full of harmonic surprises and delights. Where Verdi goes right, Dvorák goes left.

The American Symphony Orchestra performed the work at Carnegie Hall on January 25th conducted by their musical director, Leon Botstein. I repeat this again and again: Dr. Botstein has taken a lot of stick for his conducting, but in certain repertories – late Romantic and post-Romantic Central European repertory among them – he does fine work. Unlike, many conductors, he has improved with experience and time. Unlike many conductors he has improved with experience and time. Botstein maintained musical tension finding interesting details without becoming ponderous while highlighting the idiosyncratic harmonies and unabashed lyricism of the work. The orchestra played well.

There are four soloists – Leah Hawkins, soprano, Lindsay Ammann, mezzo-soprano, Joshua Blue, tenor and Stefan Egerstrom, bass, supported by the Bard Festival Chorale directed by James Bagwell. The rising young Leah Hawkins seemed more secure and in her element in the gentler, more horizontally placed lyrical lines of Dvorák. While the Verdi work exposed the seams and technical weaknesses of her lush soprano, this work kept her in a more comfortable place where her rich, radiant tone could glow and expand.

Ammann, so impressive as Anne Boleyn in the Saint-Saëns Henri VIII at Bard this summer, continued her winning streak – her contralto-ish tone has a naturally dark mournful color and she was musically astute and alert. British-American tenor Joshua Blue is also a rapidly rising up-and-comer who recently debuted at the Met. He has less to do than the other soloists, with no juicy solo aria like the Verdi “Ingemisco,” but his plangent, sweet tone was very appropriate and appealing. Egerstrom has also done small roles at the Met and his youthful bass-baritone was fresh and flexible in tone. The Bard Festival Chorale was well-rehearsed and did yeoman work in what may be the largest role in the work. Once again we are in debt to Dr. Botstein for widening our musical horizons.

Amore Opera was founded in 2009 by former singers of the lost, lamented Amato Opera to continue the good work of the late Anthony Amato and his beloved wife Sally. The founding member, Nathan Hull, tragically died of a heart attack quite young on August 10, 2020 in the midst of the pandemic at a time when the company was very vulnerable, as are all small opera companies. Nathan’s life partner of over 20 years, Ying-Chi Connie I, has taken over the company in order to continue the life work of both Nathan and the Amatos.

This Saturday night February 3rd, their new production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni ends it two-week run at the Center at West Park on 86th Street. In a credible, bare-bones but intelligent modern dress production directed by Jenna Stewart & Nicholas Wuehrmann and more than credibly conducted by the protean Richard Cordova, the unpretentious production gave full dramatic and musical value with minimal materials. One of the blights of the old Amore Opera was the amateur orchestra which played out of tune and out of sync. A somewhat smaller ensemble (likely paid) of more professional and experienced musicians gave a convincing and fully realized rendition of Mozart’s masterwork despite briefly wayward woodwinds in Act II. Cordova’s tempos were forward moving but flexible, keeping the youthful cast on their musical toes but expanding for drama or lyricism when necessary.

The production had a few set pieces, modern clothing and effective lighting which underscored the drama. The only non-traditional touch was the insertion of a new mute character of Donna Anna’s maid/companion who appeared in Act II during the allegro section of “Non mi dir.” Her relationship to her mistress seemed more than that of a servant with caresses and significant looks exchanged between the ladies. The duenna/companion returned in the final sextet. It seemed that Donna Anna’s reluctance to marry Don Ottavio had other reasons than just her mourning for her father’s murder…

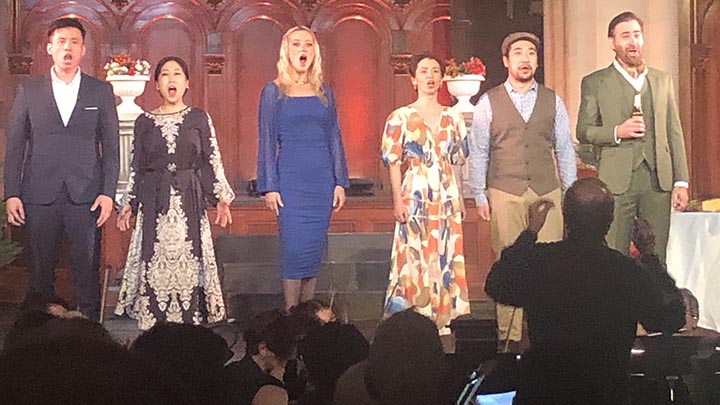

The revitalized orchestra was abetted by a youthful and fresh-voiced cast each one on top of their roles. The women in general were more impressive than the men, as is often the case with second tier companies.

As the titular antihero, baritone Muir Ingliss had a bit of the suburban sex pest lothario about him lacking hauteur and aristocratic entitlement. He’s quite good-looking and sings and moves well. It’s a handsome instrument with a slightly backward placement to increase tonal darkness but would benefit from more lightness and point. Ingliss cuts an elegant youthful figure onstage but was never threatening as the Don.

Korean lyric-coloratura soprano Yeawon Jun showed good technical command and a slender but true tone that has a bright-dark timbre which gave both youthfulness and tragic weight to Donna Anna’s music. The strikingly blonde and curvaceous St. Petersburg (Russia, not Florida) born soprano Elizaveta Ulakhovich was a fierce, not-to-be-fucked-with Donna Elvira. With her tousled hair, high heels, and too-tight dresses, Ulakhovich evoked Glenn Close in the 1980’s hell hath no fury thriller Fatal Attraction, but with no bunnies boiled. Her soprano is lean and flexible without much float at the top but Elvira’s tricky, rangy vocal lines were clearly limned.

Bass-baritone Jason Adamo was a likeable shlub of a Leporello with a grainy tone that was blessedly free of vocal mugging. With her pure-toned lyric soprano and delicate appearance, Allegra Durante was a bit more the maiden in distress rather than the peasant coquette as Zerlina – her tone is pleasingly fresh and musically used. Samuel Ng was a youthful, boyish but clueless Don Ottavio whose tone turned opaque at the top. But Ng had the breath control and flexibility to manage “Il Mio Tesoro” with some bravura which got him a big hand. Bass Virdell Williams as the Commendatore boomed his dire threats to the Don. Williams sounded mic’ed, but wasn’t – his appearance as the statue was chilling. Daniel Chiu rounded out the cast as the aggrieved Masetto with a light, apt baritone.

This was a very promising return and I hope to hear from Amore Opera in more off-the-beaten track repertory. Maybe some rare Mozart like Il Re Pastore or La Finta Semplice? I think the proposed Meyerbeer grand-opéra L’Étoile du Nordis really out of their scope at the moment but there are small-scale charmers in the baroque and 19th-century French repertoire that would benefit from revival and suit young voices.

Photos: Matt Dine and Eli Jacobson

Comments