Inspired by Greek mythology’s filicidal sorceress, the opera’s creators conjure a beguiling tragedienne whose political and romantic confrontations with the drama’s supporting characters gradually erode her humanity towards the finale’s dark apotheosis. Although Médée was the composer’s only full-scale opera, Charpentier’s gifts for pairing intensely theatrical text with imaginative melodic and harmonic inventions flesh out one of the most psychologically probing retellings of the Medea legend.

Médée unfortunately was poorly received and languished in obscurity for nearly three centuries until Jean-Claude Malgoire and William Christie revived the work during the late twentieth century. Christie’s authoritative 1994 studio recording, which coalesced around Jean-Marie Villégier’s stage production, is one of the discography’s greatest recordings of a baroque opera. Apart from being note-complete, Christie’s 1994 Médée benefited from improvements in Les Arts Florissants’ ensemble work and a charismatic cast spearheaded by the sublime Lorraine Hunt Lieberson. Listeners who are unfamiliar with this opera would do well to purchase Erato’s beautiful used sets, currently available at low prices on Discogs, Amazon, and eBay.

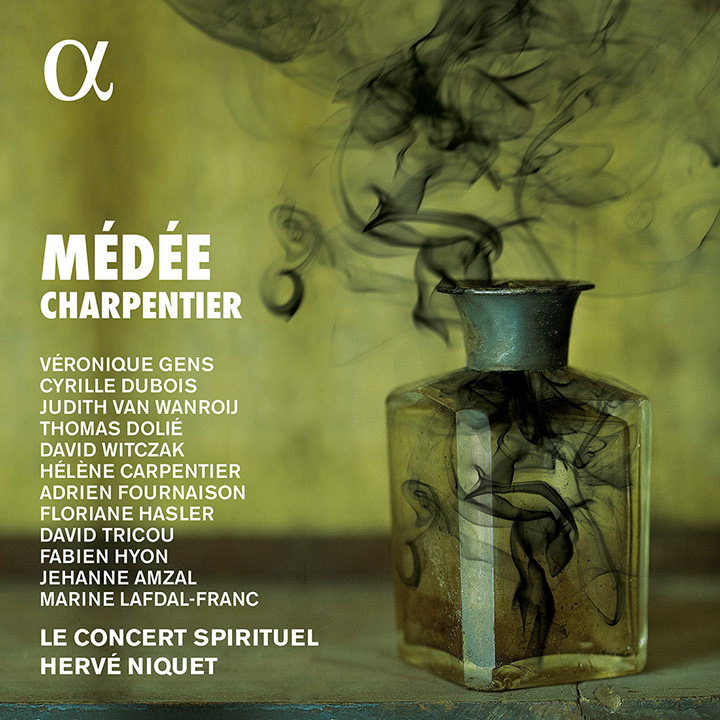

Thirty years later, a second complete account of Charpentier’s opera enters the discography, featuring a cast led by the mesmerizing soprano Véronique Gens and performed by Hervé Niquet and his ensemble Le Concert Spirituel. Underwritten by the Centre de Musique Baroque de Versailles (CMBV) and the Fondation Bru, Alpha Classics’ new studio recording presents the latest research into the period’s prescribed orchestral and choral arrangements, the stylistic executions of textures and balances with the continuo, and strict observations of the composer’s declamatory marking and ornamentations. The implementation of these findings provides a refreshing perspective into Charpentier’s harmonically opulent instrumentation and his gifts for structuring dramatic music.

Niquet’s interpretation of Charpentier’s score adopts the organic rhythms of spoken verse, allowing its seamlessly interwoven sequences of recitatives, airs, and ritournelles to unfold with play-like dramatic clarity. Le Concert Spirituel’s sonorous continuo further enhances Niquet’s storytelling by furnishing a theatrically attuned bass line to the pulse of Corneille’s verse. These instrumental balances accentuate the score’s captivating harmonies, with the scintillating period strings, mellow boxwood winds, and twangy baroque trumpets blending with an arresting polyphony reminiscent of the composer’s liturgical writing.

The ensemble’s rearrangement notably reveals Charpentier’s penchant for melodic reinvention. For instance, the listener can more readily discern the motif of Médée’s arioso “Quel prix de mon amour” underpinning her attempts to reclaim Jason’s affection as early as act one. Another notable showcase of the orchestra’s prowess occurs when Médée implores the God of Cocytus to enchant the poison intended for Créuse, as Niquet’s ensemble deftly deploys their full instrumental palette to evoke Lake Avernus seething with demonic energies and subterranean thunder.

Much like William Christie and Les Arts Florissants before them, Niquet and his forces craft a dramatic reading that dovetails his cast’s detailed musical characterizations. At the center of this dark tragedy is the commanding sorceress of Véronique Gens, whose extraordinary interpretation depicts the psyche of a heroine betrayed by her husband and rejected by society. Throughout Charpentier’s subtly crafted narrative, Gens employs her vibrant vocal palette and her quicksilver shifts of verbal articulation to recreate this powerful yet vulnerable woman. One minor caveat: the soprano is in her late fifties, and the close miking at times emphasizes the reduction of vocal bloom in her singing. Still, these issues barely detract from her riveting performance of the title role.

When listeners are first introduced to Médée, Gens’s declamation of her opening récit (“S’il me vole son cœur…de plus grands efforts feront voir, ce qu’est Médée et son pouvoir”) [If he robs me of his heart…still greater deeds will show who Medea is and what powers she possesses] radiates with power and a contained ferocity on the verge of being unleashed. When Médée learns from Oronte that Jason is to wed Créuse, she yields to her sorcerous impulses and asserts her dominion over the Eumenides and demons to engender her revenge. And when she challenges Créon’s authority as he intends to banish her from Corinth (“Quand tu te vantes d’être roi, souviens-toi que je suis Médée”) [when you boast of being King, remember that I am Medea], we become increasingly aware of her inevitable metamorphosis into an asperous demiurge who will reduce Corinth into cinders.

But Charpentier’s sorceress is so much more than an ostentatiously violent hydra, and Gens in depicting Medée’s parlous situation unearths too the wronged heroine’s more human and motherly facets. As Jason abandons her for a politically favorable marriage, the soprano colors her voice sympathetically while reminding her husband of her love and the immense sacrifices she made to secure his position. (“Mais conservez-moi votre cœur, c’est l’unique bien qui me reste”) [But keep your heart for me, it is the only possession I have left].

From Act 3 onward, Medée’s profound sense of loss severs the vestiges of her humanity until her motherly instincts too are extinguished. Gens suffuses one of her exposed récits in the final act with incredible desperation as she culminates her barbarous transformation. (“Il aime ses enfants, ne les épargnons pas. Ne les épargnons pas! Ah, trop barbare mère! Quel crime ont-ils commis pour leur percer le sein!”) [He loves his children, let me not spare them…Not spare them? Ah, too inhuman mother! What crime have they committed, that I should pierce their breasts?] So persuasive is Gens’s buildup of Medée’s dehumanization that her horrifying filicide appears uncomfortably logical and necessary to attain emancipation. If Véronique Gens is celebrated for portraying the tragediennes of French baroque opera, this bewitching Medée is arguably her finest traversal within the genre.

Fortunately, Niquet surrounds his formidable lead with a musically gifted cast fluent in the period’s idiom. Jason is played by the exceptional French tenor Cyrille Dubois, whose clear, resonant vocalism capably scales the full dynamic range of Charpentier’s haute-contre writing while maintaining impeccable diction. With his skillful deployment of the recitatives and airs, Dubois fully embodies the antihero’s opportunistic and weak-willed nature, providing listeners with additional ground to sympathize with Médée. Jason’s love interest Créuse is sung by the Dutch soprano Judith van Wanroij, whose radiant and luminous tone complements the Corinthian princess’s and contrasts with Gens’s darker, copper-tinged timbre. Van Wanroij portrays Créuse with heightened dignity, foregrounding a more assertive and combative demeanor in her final interaction with the sorceress. At the end of the opera, Dubois and van Wanroij share one of the composer’s most funereally beautiful duets as Créuse expires in Jason’s arms.

The French bass-baritone Thomas Dolié portrays the Corinthian king Créon as a severe and duplicitous politician, whose obstinacy becomes his undoing when he confronts the more savvy and powerful Médée. David Witczak in the short role of Oronte capably depicts the duped lover and the sorceress’ political accomplice. While both basses delivered solid readings, one misses the vocally firmer and dramatically more colorful presentations from Bernard Deletré and Jean-Marc Saltzmann on Christie’s recording.

Minor supporting parts like Nérine (Médée’s confidante) and Cléone (Créuse’s confidante) are played well by promising emerging artists like Héléne Carpentier and Jehanne Amzal. Le Concert Spirituel’s chorus also deserves plaudits for rendering Charpentier’s memorable choral scenes (including the obsequious “dear leader” prologue) with ravishing beauty and dramatic nuance. Under Niquet’s direction, the demons and Eumenides summoned by Médée cackle and snarl in their diabolical revelry, whereas the phantoms that ensnare Créon and his men seduce the listener with the most sensual choral tones.

With this latest recording, Alpha Classics has scored an artistic triumph and significantly enriched the discography for admirers of Charpentier’s masterpiece and French baroque music. While William Christie’s statelier 1994 studio recording remains a definitive document (one hasn’t lived fully until they’ve been sonically flensed by Lorraine Hunt’s bloodcurdling “INFIDELE!”), Niquet and his ensemble present a compelling alternative conception centered around the cast’s theatrically vivid dramatizations. Most importantly, it documents for posterity Véronique Gens’s astonishing assumption of one of opera’s most complex and tragic heroines.

Photos: Sandrine Expilly, Jean-Baptiste Millot