Carrie Cracknell’s Carmen opens onto high chain link fences in front of a drab industrial exterior armed guards with machine guns surveilling from above and army personnel loitering in flak jackets along with a group of disheveled men. We’re in a “contemporary American industrial town,” or so the program indicates, but this factory looks more like a prison than a workplace.

For a moment, I perked up; relocating Carmen—already a story about the intertwining of race and misogyny—to the US in the age of ICE detention centers and our country’s inhumane treatment of undocumented immigrants seems a very generative concept. But then the women arrived dressed in Pepto-pink coveralls with cartoonishly oversized railroad hats, and the air went right out of my tires. It was just a factory after all, though one inexplicably guarded by armed security and military personnel.

This Carmen, in other words, was somewhat less radical than its initial image suggested. It’s right on the money with its critique of misogyny, but its considerable power was ratcheted down by some incongruous design choices and a lack of specificity about its setting. The result was a more straightforward exploration of men’s violence towards women (without much attention to race or class) that seemed to reference but not truly engage with the political realities of the opera’s American setting.

Carrie Cracknell, a theatre director whose credits include productions of Ibsen, Shakespeare, Sophocles, and Euripides along with her fourth-wall breaking film version of Persuasion, makes her Met debut with this production which makes its feminist leanings explicit from the first moments. In Cracknell’s vision, Carmen’s world is rife with danger. Parties are always one wrong step from turning violent, guns are ever-present, and men leer and grope at women as they pass by.

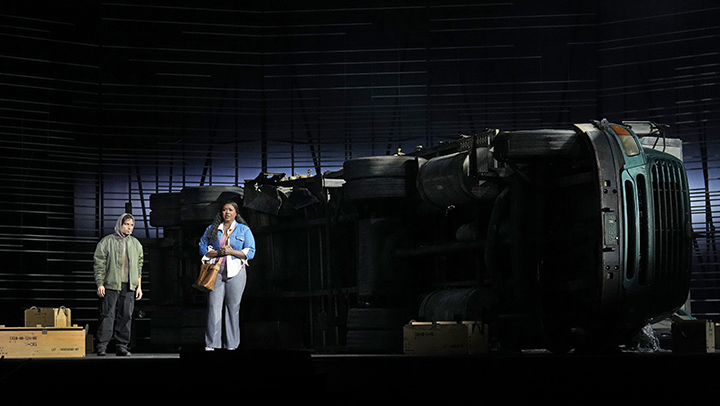

The first act takes place at the factory, where Michael Levine’s gargantuan set pinned the actors into a narrow strip downstage, effectively precluding any motion from the chorus of men and soldiers. In this simultaneously open but claustrophobic environment, we meet Aigul Akhmetshina’s Carmen, who sauntered on to the stage with calm confidence in jean short-shorts and turquoise cowboy boots. Akhmetshina, with her lithe and vigorous mezzo soprano, is an excellent choice for Carmen, whom she plays as genuinely sexy but cool and detached with men. One doesn’t believe her when she says she loves him, but it becomes increasingly clear why someone like the anxious and weak-willed Don José would become obsessed with her; she gives just enough of herself to keep him interested without giving herself away.

Don José (Rafael Davila, stepping in at the last moment for a sick Piotr Beczala), was impressively spineless in this production. Carmen, the polar opposite of his hometown girlfriend Micäela (Angel Blue), utterly fascinates him with her sexual agency and, perhaps, her helpful habit of never mentioning his mother. Carmen seems convinced that she will retain the upper hand with him, but even spineless, entitled men are dangerous too, perhaps even more so.

At first, however, Carmen has him instantly in her thrall. After her successful seduction and escape from prison in Act I (an act which costs José some jail time), during which Carmen and her friends Mercédès (Briana Hunter) and Frasquita (Sydney Mancasola) steal an 18-wheeler from the factory where they work and drive us right into the opera’s major set piece, there are four full-size vehicles driving onto the Met stage and drive, wheels spinning, as characters sing.

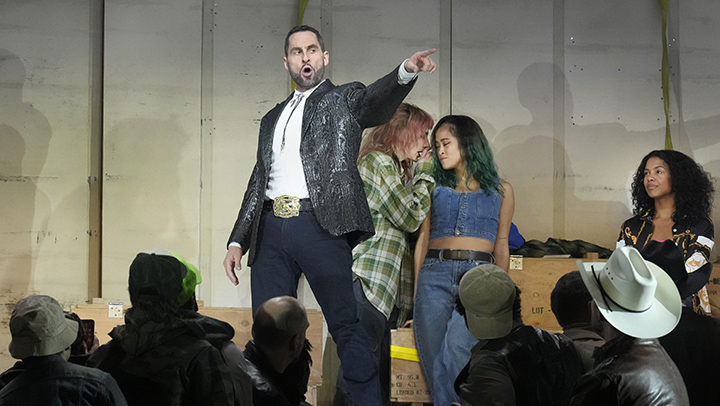

The Mad Max Carmen Road segment filled up the stage with light and motion, as Carm and the girls partied in the truck bed as it hurtled down the highway. Trucks packed with good ol’ boys toting a terrifying array of sub-machine guns pulled up alongside the truck, their raillery carrying a palpable undercurrent of danger. Escamillo, now a rodeo rider in a red Mustang convertible, sauntered in to hang out at the tailgate. There, the ladies are joined by smuggler friends Dancaïre (Michael Adams) and Remandado (Frederick Ballentine). They sang the famous quintet from the bed of a moving Ford F-150, in a moment of dynamic direction and set design paired with crisp and enthralling singing from all of the leads. It was easily the high point of the first half and used Levine’s set and Guy Hoare’s lighting to make an already dynamic piece of music actually drive forward.

Here, however, was where Cracknell’s setting and Tom Scutt’s costuming began to seriously get in their own way. The car element looked stylish and impressive, but it also introduced confusion. Carmen and the smugglers kidnap Zuniga (Wei Wu, in a strong Met debut), but they don’t do anything with him. He simply disappears. José wanders in without a car but finds Carmen at a gas station, and then wanders off again on foot. Where is all this happening, anyway? Texas?

Scutt’s costuming did little to help matters. While Carmen and her friends are were clearly styled as blue-collar Western—cut offs, cowboy boots, tight t-shirts, Dancaïre was wearing tracksuit pants, a tight tank top and a colorful Hawaiian shirt that more said off-duty Palm Springs circuit than a hardened smuggler, while Remandado, in a black suit with pink baseball cap screamed finance bro on spring break in Miami. Other chorus members, rocking split-dyed green hair, Doc Martens, and septum piercings. with looked like college-aged lesbians. And everyone had guns: not just little pistols, but machine guns.

Normally I wouldn’t harp so hard on costuming, but here it was not only visually jarring, but actively confusing. I knew less about the particular aspect American culture that was being interrogated because the characters were dressed as if from very different regional and socioeconomic backgrounds, whereas it’s quite clear in the libretto that the smugglers are all part of Carmen’s community. It’s emblematic of the whole production, which doubles down on the notion of contemporary political relevance but can’t fully commit to outlining precisely what that relevance is. Who are these characters in their world? What types of power and influence do they each have and what is the source of it? Without clarity (or at least consistency) on these points, any political statement that Cracknell is trying to make becomes muddled.

This vagueness is most suffocating in the absence of clearly-signaled racial and ethnic identities of the characters. In Meilhac and Halévy’s libretto, Carmen’s status as a “gypsy” is both what makes her enticing and what renders her killable to Don José. She’s a woman, she’s sexually open, and she’s a racialized outsider to Don José’s world. Carmen, in other words, always been about intersectional identities. The problem with Cracknell’s production is that the audience doesn’t know what specific identities we are supposed to map on to the characters, and the otherwise realistic contemporary setting means that we can’t help but ask. Even with a racially-diverse cast, the production could have indicated this through visuals or even by simply telling us in the program notes.

The production almost gave the impression of having once been a more concrete and more confrontational idea, where placing Carmen in a more pointed and specific context would simultaneously indict misogyny in general and a racist machine that renders some female bodies disposable. The very real plight of native women and of migrant women, who disappear and are killed at staggering rates compared to white women, means that such a reading of this classic opera has the potential to be blazingly radical and relevant. But that’s only when the mechanism of the oppression is made clear, which would also mean naming specific oppressors and risking anger and backlash.

What we were left with is a collection of images that resonate strongly with contemporary conversations about migrant women—the silhouette of Carmen that emerges from the misty scrim, the image of the girls sitting in the truck trailer which recalled of similar representations of border crossing or even human trafficking, the ubiquitous guns that threaten to go off in every scene, mentions of border guards and armed men standing before chain-link fences—but these images aren’t borne out in the rest of the drama. The silhouette Carmen that appeared between each act evoked a fundamental loneliness to the character that, for all of Akhmetshina’s work (and it was very good work), simply was not there in the acting. The suggestions of migrant narratives are never concretized; the girls simply party happily in the trailer, taking selfies, dancing wildly, and looking at Don José’s Instagram. Chekhov’s guns don’t go off.

For better or for worse, the actors could have been in any Carmen. It was both sung and played quite straightforwardly and effectively by all involved. Daniele Rustioni’s vivacious and clarifying conducting showed Bizet’s score off to best advantage, and everything moved at pleasant clip, zippy but not rushed. Akhmetshina sang with such relaxed power that I wouldn’t be surprised if she could have sung the whole show again as soon as the applause died down. As José, Rafael Davila had something of a thorny start with his “La fleur que tu m’avais jetée” which alternated between whispered and shouted, but his voice blossomed in the second half, revealing a more expansive palette and increased presence. Angel Blue, as (Don José’s) mommy’s girl Micäela (wearing so much denim that it seems Scutt must have wanted us to call her Angel Blue Jean), brought warmth and depth to this ingenue, and sang the beastly-difficult “Je dis” with ease. This wasn’t my favorite performance of hers, but Blue imbues her characters with such dignity that she can’t help but be sympathetic, even when Micäela is frustratingly naïve. Kyle Ketelsen looked and sounded strapping and robust as Escamillo, his flexible, flinty baritone matched with a cocky self-assurance and eventually an enormous pair of rodeo chaps. Sydney Mancasola and Briana Hunter were both excellent as Frasquita and Mercédès, perfectly cast with each other and with Akhmetshina, as were Michael Adams and Frederick Ballantine.

For all my ranting, Cracknell deserves credit for her reimagining, which I hope marks a turn towards having more female-led productions of classic works. Her Carmen, while flawed, took a wonderful turn in the second half. Played more a bit closer to the libretto and thus with fewer logical flaws, these sections were much stronger and clearer, and the final act was excellent on nearly all fronts. The rodeo scene, which used the rotating stage and expertly rendered the cacophony of the stands and the antics of the rodeo clowns, was both visually engaging and dramatically intelligent. Carmen, picking her way through the scaffolding to escape José, only to find herself briefly caged, was one of the most dynamic bits of blocking in the whole evening.

Here, Cracknell’s feminist stance was also at its clearest and most powerful. After Don José bludgeons Carmen to death with a baseball bat (not, strangely with one of the thousand guns we’d seen on stage thus far), security is alerted. Each one gazes at Carmen’s body and turns away, stone-faced and unresponsive, while each woman in the bleachers stands up to bear witness to Carmen’s body. This coup de grace was powerful indeed, a clear indictment of patriarchal power structures: how they rarely procure justice for women, how often they simply avert their eyes. The final image alone is fresh enough to make Cracknell’s production sing.

Photos: Ken Howard