Daniel Catán’s Florencia en el Amazonas is the third work in Spanish to be performed at the Metropolitan Opera in the company’s history. It ought to feel like the beginning of something new. Indeed, the eagerness of Thursday night’s audience was palpable, with a rallying voice crying “Viva la ópera en español!” moments before Yannick Nézet-Séguin brought down his baton. However, while Florencia might be new to the Met—and while “la ópera en español” is certainly an exciting prospect—it is also a 27 year old opera, written to sound much, much older. In its Met premier, neither a talented cast nor some beautiful musical moments were enough to make Florencia feel new or vital.

The Florencia program note leads with an acknowledgement that “critical responses” to Catán’s opera “often compare the opera to the music of another composer.” I hardly want to harp on this well-worn theme, but I also cannot deny that Florencia resembles a study in Puccini pastiche—or a new take on WQXR’s Opera Quiz, where fans could compete to identify the opera’s many musical and textual references to the greatest hits of the operatic canon. Referentiality is all well and good, but the comparisons invited by Catán’s music ultimately do no favors to Marcela Fuentes-Berain’s libretto, which is frustratingly unsubtle and banal.

Take, for example, the titular diva Florencia Grimaldi’s first act aria. Florencia is on a riverboat down the Amazon, traveling incognito in search of her lost lover, Cristobal, who awakened her almost magical musical talent years ago. Alone on the deck of the El Dorado, Florencia describes her desire to return to a time before she became La Grimaldi and to reconcile the lover she was then with the artist she is now. In its contemplative build to a soaring heart-song, Florencia’s aria is musically reminiscent of Minnie’s act one aria in La Fanciulla del West. Minnie’s text, too, could be termed banal: she describes her parents’ marriage, how she used to see them playing footsie under the table while they played cards. But the simplicity of Minnie’s words is an intentional contrast to the grand sweep of Puccini’s music. Together, words and music combine to convey the idea that below Minnie’s simple, country-girl affect lies an almost unbearably vast emotionality that must burst out in song.

Florencia’s aria, too, is explosively emotional, but her text is banal in another way entirely: Florencia merely states that she has loved, that she longs to find her love again, that she cannot be wholly herself until she does so. Her words and her music make the same statement. Together, they convey nothing more than the facts—far less than the sum of their parts.

This aria is a waste of a good Puccini pastiche; on Thursday, it was also a waste of the very good Ailyn Pérez. Pérez’s voice may not have been the largest, but it had a remarkably dense, supple quality—columnar, almost. If Catán’s orchestration, as the program note claims, seeks to reproduce the ambient sounds of the Amazon, Pérez’s voice was like a river snake, rippling elegantly through the waters. As Florencia, Pérez shone with a sincerity and depth of feeling that made the libretto’s banality all the more frustrating. I wanted Pérez’s Florencia to have her Minnie moment—or her Mimi moment, or her Tosca moment—but that alchemy of music-drama just isn’t in Florencia, despite the libretto’s repeated insistence that the opera will be a space of transformation.

Indeed, Fuentes-Berain’s libretto was inert in ways that not even an energetic cast of singers could combat. The opening scene’s glut of exposition, for example, was delivered commandingly by Mattia Olivieri as Robiolo (you’d never guess it was his Met debut), but neither his muscular tone nor confident stage presence could disguise Robiolo’s inelegance as a narrative device: a semi-magical narrator who exists to, in the very first scene, tell the audience all the relevant facts about the other characters’ lives, conflicts, and desires.

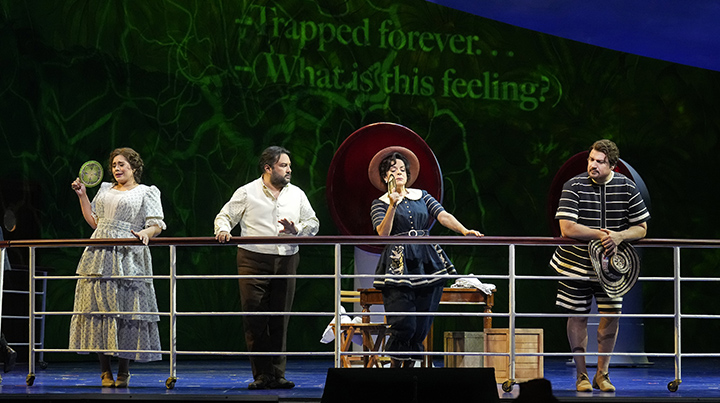

These facts comprise the entirety of what those characters themselves will articulate over the course of the opera, so one wonders why they are imparted immediately after the curtain rises. Robiolo tells us, for example, that the Captain’s nephew Arcadio is dissatisfied with his life on the river. Not ten minutes later, Arcadio, sung with infectious energy (if not entirely enough volume) by Mario Chang, comes on stage and announces that he is dissatisfied with his life on the river. As Arcadio’s love interest and Florencia’s would-be biographer Rosalba, Gabriella Reyes was charmingly passionate, with a lovely, unfurling quality to the top of her voice.

Arcadio and Rosalba have two character traits each: he wants to be a pilot, she’s writing a book, and they’re not sure whether to succumb to the love they feel for one another. As the quarreling married couple Paula and Alvaro, Nancy Fabiola Herrera and Michael Chioldi had even less to do, but even so they did it well, bringing comic timing to their spats and emotional sincerity to their reconciliation.

That reconciliation, however, was marred by the inertness—or more accurately, the sameness—of the score itself. The music is beautiful, textural, swelling to a crescendo before ebbing back to its beautiful texture. And then it does that again. And again. In the pit, the superhumanly consistent Yannick Nézet-Séguin and the Met orchestra gave all that beautiful texture a lushness and a balance despite the lack of excitement.

A similar consistency without drama characterized Mary Zimmerman’s staging. As has often been the case with Zimmerman, Florencia was presented in a style that could perhaps be termed “gestural realist”—a mostly bare stage, with some lightweight, modular set pieces that ground the production in the facts of the libretto. In the case of Florencia, that bare stage was the river, cradled on either side by curving banks of vegetation-green LED screens that evoked a collaboration between the sculptor Richard Serra and a Windows screensaver. The realist set pieces, wheeled on and off, were curved sections of deck railing and those big pipes you see on boat decks in old movies.

This is gestural realism: the staging is abstracted somewhat, but the deck pipes and railings inform us that the setting is, in fact, entirely literal. I am by no means opposed to realist productions, but Zimmerman’s staging struck me as frustratingly noncommittal, hedging its bets with a stylized aesthetic that was nonetheless painstakingly non-threatening and almost entirely unsurprising.

Just about the only staging choice that seemed capable of surprising the audience was its least realist element: the dancers who animated, through some Lion King-esque puppetry and choreography, the flora and fauna of the Amazon. Swishing as schools of fish across the stage in piranha headdresses and piranha panniers over blood-red ball gowns, these dancers seemed like brief flashes from another production—one with just a little more imagination.

At its best, non-realist theater is necessarily somewhat semiotic; the objects and images onstage don’t represent the facts of the setting or the libretto, so, ideally, they present something else about the work instead, something below the level of the literal. Zimmerman’s lightly abstracted minimalist realism has the virtue of stylishness—a virtue not to be discounted—but her Florencia lacked the layers of meaning that successful non-realist theater can provide.

A lack of semiotic depth isn’t inherently a problem. Often, a primarily stylish production has the benefit of getting out of its own way and enabling a work to speak for itself. The problem with Florencia, however, is that despite the press materials’ repeated invocation of the term “magical realism,” it itself suffers from a lack of layered or implicit meaning. At times, it seemed as though neither the work nor the director had much to say at all.

Tellingly, this missing point of view was most noticeable in moments where the opera claimed to plumb some Amazonian depth: moments where Florencia promised rupture, transformation, even apocalypse. The storm sequence that maroons the riverboat, for example, includes in the libretto a plea to the gods that they not end the world—but the score provides nothing more catastrophic than some timpani rolls, and the staging nothing more transformative than a rain of confetti and the deck railings tipped over on their sides.

No catastrophe, it seemed, was enough to break the smooth, harmonious consistency of Florencia’s score and staging—to dredge its placid depths and pull anything of real meaning to the surface. Instead, its bare stage was for the most part just that: a bare stage, full of beautiful music, signifying nothing.

Photos: Ken Howard/Metopera