Unholy Wars, the third offering in Festival O23, is an opera of a kind, but one that requires some explanation.

Most of the score is an assemblage of musical pieces by late Renaissance and early Baroque composers including the Caccinis (Giulio and daughter, Francesca), d’India and others—some are excerpts from longer works, and all of them brief, though Monteverdi’s Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda is, I believe, performed complete.

Interspersed are interludes by contemporary composer Mary Kouyoumdjian, whose style riffs on aspects of early music, particularly through wordless choral lamentations—while also sounding much more modern, including the use of amplification.

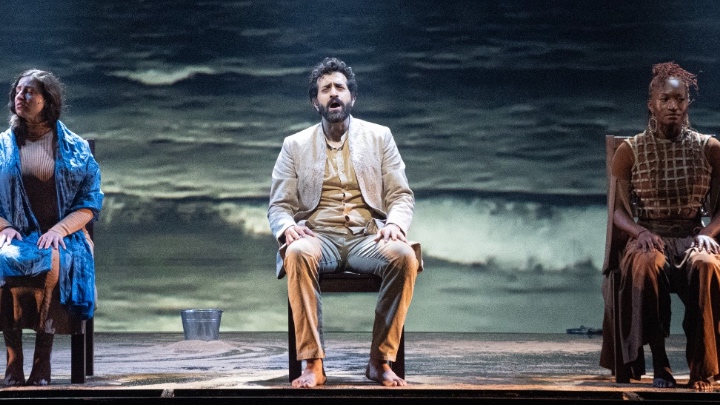

Much of Kouyoumdjian’s music is prerecorded. The rest is accompanied by a chamber ensemble (musical direction is by Julie Andrijeski) and performed by three onstage singers: Karim Sulayman (tenor—he’s also credited as the work’s creator); Raha Mirzadegan soprano), and John Taylor Ward (bass-baritone). A dancer (Coral Dolphin) interacts with group, forming a quartet. The production director is Kevin Newbury.

Unholy Wars’ dramatic structure is similarly amorphous. Rather than focusing on a narrative, it explores a series of timeless yet current themes: war, destruction, alienation, and what it means to be perceived as outsider—particularly from the Middle East—in the context of a violent world.

These visions are seared into the fabric of Unholy Wars through powerful projected images (projection design is by Michael Commendatore, visual design by Kevork Mourad). They take the form of stark, animated drawings that recall bold modernists—I thought of Paul Klee and Oskar Kokoschka, among others—that are constantly growing, changing, and decaying.

For me, the attention-grabbing design, at once beautiful and sinister, consistently overwhelmed what was happening on stage, with only Coral Dolphin’s gracefully balletic, elegant presence really registering. (She’s also strikingly costumed in flowing silks.) The singers, too, participate in the stylized movement with slow, ritualistic, solemn gestures that reinforce the almost unrelentingly somber musical world, but understandably, they don’t have the same range of motion.

While the musical forces here are in fact larger than one would normally hear in this very “private” music—most of it laments and in minor keys—the three singers approach it with HIP (Historically Informed Performance) style, which includes minimal vibrato, mostly low dynamics, and largely keeping their voices in check, limiting the resonance. Tellingly, I thought they sounded best when singing as an ensemble.

The exception here is the finale: “Lascia ch’io pianga” from Handel’s Rinaldo. Composed for a theatrical work, it is likely to be the most familiar piece on the program. It’s also from a later period and in a quite different late Baroque style. Sulayman’s performance recognizes this—the voice is fuller and more vibrant, the dynamic range larger, and he employs many effective ornaments.

This is the moment where Unholy Wars fully achieves lift-off, with the visual elements finding a similarly full-scale musical equivalent. Elsewhere, the piece languishes too often in a reverent mood that lacks the theatrical variety needed to sustain its 70-minute length.

Devotees of early music may react very differently to than I do… but from that side, I think the performance style of Unholy Wars will pose a different issue, seeming too inflated for what is essentially very intimate music.

For me, the conclusion is ironic but unsurprising: Unholy Wars is most an opera when it is, with “Lascia ch’io pianga,” actually an opera.

Photos: Ray Bailey

Comments