On Saturday evening April 23, DiDonato brought her personal project to the stage of Carnegie Hall. Her collaborators, as on the Eden cd, include the Il Pomo d’Oro ensemble led by the young and gifted Maxim Emelyanychev, who will accompany her on her journeys.

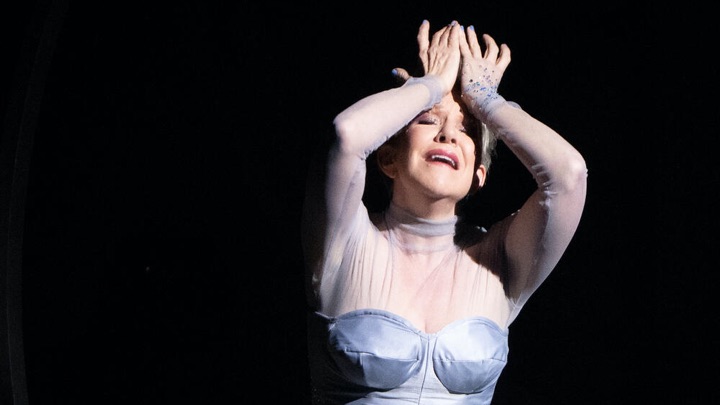

The Eden concerts (as in DiDonato’s controversial earlier attempt at multi-media concert performance War and Peace) include such theatrical conceits as costumes, props, scenic units, mimetic gestures, dramatic lighting, smoke effects, etc. But this time dance was absent despite the billing in the program of Manuel Palazzo, a handsome Argentine dancer and actor, who was a collaborator on War and Peace but was absent onstage.

Marie Lambert-Le Bihan is credited as the director and one wondered if some editing and pruning were done to the staging? If so, it was probably to the benefit of all since War and Peace was criticized for being busy and pretentious. (Palazzo’s bare chiseled torso got better reviews than his dance contribution.) Eden has more simplicity and focus on the central performer without distracting bric-a-brac and visual excess. The rather crude lighting design by John Torres unsubtly splashed the stage with primary colors but the limitations of Carnegie Hall’s lighting facilities may be partly culpable.

DiDonato’s stated mission is to restore humanity’s connection to the natural world through music, healing the wounds that our recent social, political and medical travails have inflicted on our collective psyches. DiDonato admits that she is “a problem solver, a dreamer, and—yes I’m a belligerent optimist.” She is asking questions of the world but the answers are still somewhat beyond her.

The 90-minute concert without intermission began with a reading of Charles Ives’ anguished The Unanswered Question in which DiDonato took over the trumpet solo which functions as the questioner as she wandered up the aisle singing a wordless vocalise and ascended to the stage.

Wearing a sleeveless gown in metallic pale silver blue, the diva gravitated towards a circular structure center stage with semi-circular arches protruding from it which the diva often carried about like an archer’s bow emulating the goddess Diana. The circular fragments were later connected into complete circles which provided a revolving scenic frame for our protagonist.

The musical program traveled back and forth over four centuries with a special emphasis on the baroque, classical and contemporary English-language genres. Two songs from Gustav Mahler’s Rückert Lieder and “Schmerzen” from Richard Wagner’s Wesendonck Lieder (presented as an encore) provided her sole foray into late Romanticism.

A great deal of the German lieder repertory is based on poetry (by Rücker, Heine, Goethe, Rellstab, Müller, et al.) concerning the individual narrator alone in nature turning inward to explore his own emotional landscape. There the protagonist confronts his own angst whether it be caused by loneliness, isolation, loss of romantic love or seeking some spiritual salvation. French chanson also habitually evokes nature in more sensual, symbolist terms—yet French repertory was entirely absent from the program.

There was one original work, the New York premiere of British composer Rachel Portman’s The First Morning of the World set to a poem by Gene Scheer. The narrator is trying to learn the language of trees. Yet nature provides solace but no answers. The shifting harmonies, shimmering strings and lack of musical resolution in Portman’s setting reflected the beauty of nature as well as spiritual yearning.

DiDonato’s journey towards reconnecting to nature veered from Mahler’s “Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft” from the Rückert-Lieder to a long sojourn into the baroque and classical. Orchestral ritornellos by such lesser-known early baroque composers as Marco Uccellini and Giovanni Valentini provided temporary respite showcasing the superb playing of Il Pomo d’Oro. Gluck’s “Dance of the Furies” from Orfeo ed Euridice was more familiar and evoked nature in turmoil.

Mozart’s elder contemporary Josef Myslive?ek’s “Toglierò le sponde al mare” from Adamo ed Eva found DiDonato an avenging angel confronting nature as an antagonist in cascading runs. Directly after that Aaron Copland’s “Nature, the gentlest mother” from 8 Poems of Emily Dickinson found a timid contemplative protagonist gently supplicating nature’s gentleness.

Gluck’s “Misera, dove son! … Ah! non son io che parlo” from Ezio was more demented diva in distress than smelling the flowers—this wide-ranging dramatic scena found DiDonato cursing fate on the banks of the Tiber. Biagio Marini’s “Con le stelle in ciel che mai” was a Monteverdian ode to nature to strumming lutes with Maestro Emelyanychev on recorder for a showy solo.

Francesco Cavalli’s “Piante ombrose” from La Calisto provided the occasion for more diva defiance including the cry “Non più guerra!” (No more war!) that stirred the hearts of most of us in attendance. These pieces leaned heavily on DiDonato’s coloratura technique which remains impressive and precise in her early fifties.

The final two pieces, Handel’s “As with rosy steps the morn” from Theodora and Mahler’s “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen” from Rückert-Lieder found our protagonist looking to God’s light in nature and then turning inward lost to the world in a realm of inner peace and calm. (Handel returned for an encore with “Ombra mai fu” from Serse.)

DiDonato’s voice has changed over time: the timbre once homogenous, honeyed-toned, sunny yet rich has with maturity turned into a cooler silvery sound with a soprano-like top. The tone floats easily in the upper register while the middle register is full of shifting mezzotint colors.

The lower register Sunday night sounded hollow and raspy. Occasionally there is a brittleness and prominent vibrato but this somehow adds a slightly broken vulnerability and appealing humanity to her singing. In many ways it is more important what DiDonato does with her voice than the actual sound of the instrument itself.

While watching this concert I was reminded of two charismatic and fiercely individual female performers. The first was the dance legend Martha Graham: DiDonato ascending a navigable scenic sculpture similar to Isamu Noguchi’s while exploring the inner torments of a female protagonist evoked the modern dance pioneer. Her contemporary yet timelessly simple gown and sculpted coiffure furthered the resemblance to the 20th century dance diva.

Much of the repertory DiDonato sang (Handel’s Serse and Irene in Theodora) were Lorraine Hunt-Lieberson specialties and evoked memories of the late mezzo-soprano who died in 2006. In 2001, Hunt-Lieberson performed a staged concert of two Bach cantatas “Mein Herze schwimmt im Blut” and “Ich habe Genug” conceived and directed by Peter Sellars which prefigured Eden in many ways. Hunt-Lieberson’s artistic credo of digging deep and soaring high is one that DiDonato aspires to and admires despite their being very different artists.

The evening was held together by DiDonato’s personal charisma and commitment and the superb musicianship of the mezzo-soprano and Il Pomo d’Oro. The wide-ranging eclectic program revealed a lot about DiDonato’s versatility and ambition but whether the evolution of the protagonist and her relationship to nature was embodied or merely imposed on the material is open to debate. I was involved and entertained throughout even while questioning how the material advanced the concept or specific choices that were made.

In a long post-concert speech, DiDonato thanked the audience for being there for her after such a long hiatus and invited onstage a youth chorus from the educational program Salute to Music and the All-City High School Chorus for an original song, “Seeds of Hope” (this song is a fixed part of the program utilizing local children’s choirs).

DiDonato sang with them and it was hard not to be moved by their innocent joy in music-making. Ultimately making music together is healing and replenishes the soul just as much as connecting with nature. So that part of DiDonato’s mission was fulfilled admirably.

Photos: Chris Lee

Comments