David Fox: Wow, Cameron—you’re feeling a lot more generous about this than I am! To me, the Huston film is almost a total debacle from start to finish, and only enjoyable or even comprehensible for a few moments of unintentional high camp. I shouldn’t be surprised, since while watching it, I realized two things: 1) Considering that the play is generally regarded by critics as the point of no return for Williams, it’s actually done quite often—in fact, after Streetcar and Glass Menagerie, it’s the play of his I’ve seen most often: at least four productions, each at a starry professional level. 2) Why do I do this to myself? I’ve never seen one that convinced me the original short story should have been adapted for the theater. But literally none of the stage versions I’ve seen was remotely as adrift as this film.

CK: I definitely regard the play more highly than you do. To me, it documents perfectly the shift in Williams’ focus from plot-driven early dramas to the more experimental, characterful writing that occupied him until his death. The film’s greatest weakness is that it doesn’t really capture that at all—instead, Huston turns it into Peyton Place on the Riviera. (The movie poster’s original tagline: “One man…three women…one night…”) But since we’re not going to agree on the source material, perhaps we should consider what’s actually at hand? I’ll say that among other things, the flashback introduction, showing the Reverend T. Lawrence Shannon cracking up in front of his congregation, is so misguided that it sets a bad tone the rest of the film can’t shake. It also allows Burton, never a subtle performer, to dip into his worst excessive impulses.

DF: Oh my god, that framing device. I almost couldn’t believe it. When we wrote about The Fugitive Kind, I pointed out that the unnecessary opening there almost kills the movie from the start… but at least that one proves to be only a fleeting distraction. Here as you say, it’s emblematic of the whole. Burton’s performance starts on the wrong note, and descends from there. His voice is, as always, one of the glorious instruments of the theater. And boy, does he know it—he’s in full oratory mode, and he might be reading Dylan Thomas. (The Welsh accent makes absolutely no sense here, but it’s lustily employed.) By the mid-point in the movie, Shannon—whose gradual disintegration should take up most of the play—is already frothing at the mouth. I think you’d have to look to The Exorcist Part II to find a worse or more perverse Burton performance. And unfortunately, he’s not the only one.CK: Indeed. I literally laughed out loud when Deborah Kerr, in her primmest, off-to-meet-the-queen accent, declared that she was “born and bred in the fishing village of Nantucket.” I’m generally a Kerr fan, but she’s almost irredeemably bad as Hannah Jelkes, the role that’s come to be viewed as the play’s center—due in large part, I’m sure, to Margaret Leighton’s legendary, Tony-winning performance in the original Broadway production.

DF: Leighton may well have had trouble with accent, too—I have no way of knowing. But I can’t imagine that she didn’t find a depth to the character that’s entirely missing here. Including that Kerr—in the dire Mexican heat that everybody seems to feel is consuming their very souls—has not a hair out of place.

CK: Hannah describes herself as a Yankee spinster, and her personality crosses gentility with flintiness. But she’s also a hardened grifter, who makes her living duping tourists into buying her dubious artwork. If Kerr seemed like she was putting on a rouse with her overstated accent, that would be an interesting choice. But she mostly acts like she’s in a Philip Barry play rather than something by Tennessee Williams.

DF: Every time she enters a room, you imagine she’s coming through French doors and carrying roses she just cut from her lovely, lovely garden.

CK: The worst part is that when she isn’t bad, she’s just boring—and she and Burton exhibit zero chemistry in the two big scenes between Shannon and Hannah.

DF: When I mentioned camp earlier, I was thinking specifically of those scenes, where she and Burton—who is literally shackled to prevent Shannon from harming himself or others—act as though they’re starring together in Blithe Spirit.

CK: Gardner has the opposite problem—if she had no lines, she would have given a perfect performance. Physically, she looks every inch the seductress, even with a few miles of wear and tear on her exceptionally beautiful face. And she’s never more striking a presence than when she stands perfectly still. But once she opens her mouth, she sounds like a braying Southern housewife, and she cannot help but punctuate every word with a corresponding overstated gesture.

DF: While Gardner has been used effectively in films—and certainly her physical presence is always remarkable—her acting skills are, to put it generously, limited. Here, she comes off like a community theater leading lady. And her accent seems to get thicker and more Southern with each scene. If the movie went on longer, she would have turned into Minnie Pearl. Honestly, when your three-star movie is stolen by Sue Lyon, you know you’re in trouble—but that’s what happens here. Lyon is funny and sly and utterly at home on screen. Which puts her way ahead of everyone else, including the Oscar-nominated Grayson Hall as Miss Fellowes, who here could easily be mistaken for Everett Quinton in The Mystery of Irma Vep. Once again, we’re back in camp world.

CK: Indeed, Hall comes across like a hard-charging matron from a girls’ reform school. The other members of Shannon’s tourist party might be Maenads from a particularly unsubtle production of The Bacchae. I do think “Baptist Female College,” where these women are on the faculty, is one of Williams’ best fictional names, though…right up there with Cabeza de Lobo.

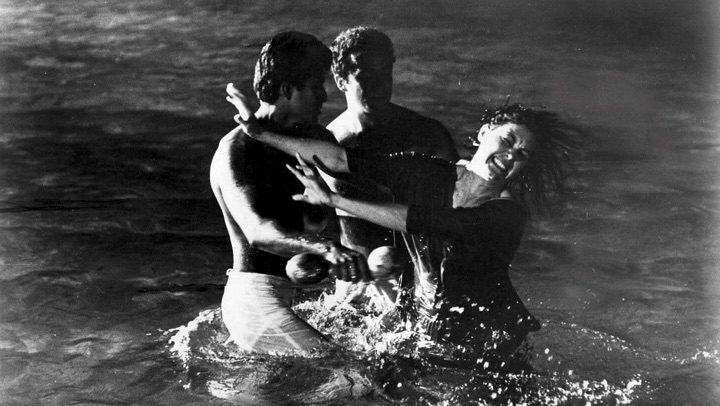

DF: More camp with the names and the crazy ladies. I’ll add one more landmark scene for me—Burton madly clutching and pulling on a crucifix around his throat. Okay, another one: the two hunky maracas-playing Mexican boys beating up the equally hunky bus driver (actor Skip Ward—what’s his story?) But I digress. Having taken virtually every actor here to task, isn’t it time we bestow blame where it’s most deserved? Squarely with Huston. A great director many times over, he seems completely flummoxed here. I doubt he has any idea what Night of the Iguana is about. Moreover, he seems to have encouraged every actor to go their own way, and do it as grandly and hammily as possible. No two performances look like they’re in the same world. Again, The Fugitive Kind could serve as a touchstone. There, Sidney Lumet works with his two stars, Anna Magnani and Marlon Brando—actors of famously volcanic temperament—and miraculously gets them to fine down their performances to some of the quietest and most emotionally affecting acting I’ve seen on film. What we have here is at the other extreme. But honestly, I can’t get away from feeling that some of the problems here are unresolvable and hard-wired into the play.

CK: Again, I don’t think the material itself is as treacherous as you do, and I think we’ve both seen actors on stage more than pull it off. But I agree that Huston allows the central actors to give extremely siloed performances in a work that’s all about the complicated connections between people.DF: Huston, we have a problem. But seriously, as much as I adore Williams’ even at his most baroque, I feel the Mexico setting is simply alien territory for him, and he doesn’t find his way. I feel similarly about other Williams’ geographical excursion plays. This Tennessee is too far south.