And marketing, moving and Maureen Dowd aside, there remains, at least in my mind, a reluctant mythos to the American soprano, who, at 61, seems to be simultaneously perennially fresh yet inexplicably passée.

To bemoan her is to naïvely discount her visible diligence as an artist, risk-taking nature with repertoire and lustrous tone. But to exult her above all others means drawing unfavorable comparisons between her and who are often more versatile or temperamental artists, especially in Mozart and Strauss, and an endorsement of the endemic, ear-pleasing sameness from all too many conservatories and young artist programs.

How do you discuss a singer whose justifiable yet elusive trailblazer status is consistently contradicted by her own presentation, whose pop-culture recognition has been attained almost completely outside the music made her known to opera fans, whose new “Undiva” monicker appears neither warranted or earned?

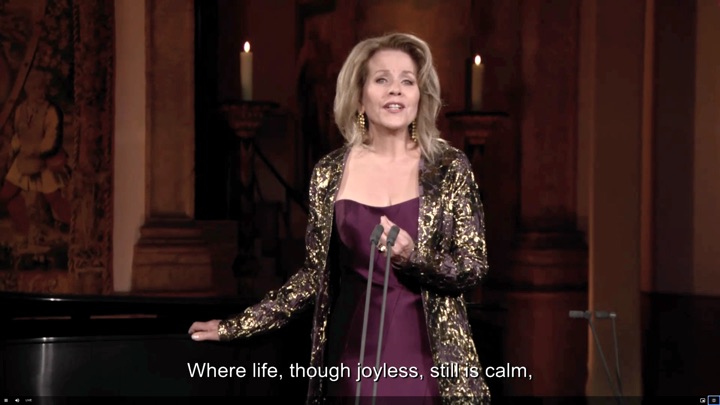

For me, and I imagine for many other spectators with less complicated relationships to the Fleming aura than mine, the Met’s stream provided an ideal place to begin those discussions. Ensconced in the Music Room of Georgetown’s Dumbarton Oaks (a scant few blocks from where I am currently spending the summer), a space that literally reverberates with both political and musical history, Fleming presented a satisfyingly (and surprisingly, for how the series has been marketed) eclectic and quietly daring program of songs and arias, an interesting timestamp on a career that, despite its crepuscular vibe, seems as active as ever.

Maybe the most infallible characteristic of Fleming’s career is her linguistic ravenousness. The program spanned five languages and from the Baroque to Korngold to 2020 and was spliced in between with particularly juicy bits of Fleming’s Met filmography. The program began with a world premiere John Corgliano song, written for Fleming and set to Kitty O’Meara’s ubiquitous poem “And the people stayed home.”

Unaccompanied by pianist Rob Ainsley, who otherwise provided diligent support throughout, she sang with the a capella aimlessness of the song’s jazzy Gregorian chant style. Formulaic yet responsive to the poem itself, its somber mood matched the dimly lit Music Room. The excerpt from Händel’s Alexander Balus that followed, “Come now my Soul,” bloomed into the acoustically collegial microphones and even featured a nice trill.

The subsequent two hedonistic Händel excerpts, however, proved an early nadir. “To fleeting pleasures make your court” from Samson was gurgled and gargled beyond recognition and accompanied by what I can only call the most contrived sort of Jezibaba hand gestures. That “Endless pleasure, endless love” from Semele fared better might be more of a credit to William Congreve’s delectably singable libretto than to Fleming’s approach. While the voice admirably retains a coloratura nimbleness, words do not sit well atop it and ended up mostly swallowed or not articulated.

Other selections, however, proved more congenial or even stunning. The sleeper highlight of the afternoon was Reynaldo Hahn’s setting of Victor Hugo’s “Si mes vers avaient des ailes,” which was delicate, lovely, and clean. A pair of Joseph Canteloube songs from the Chants d’Auvergne sung in Occitan, “Malurous qu’o uno fenno” and “Bailerò,” were respectively jocular and confiding, plus a welcome break from the standard languages these recitals tend to encompass.

The rest of the program contained mostly arias. For a singer who is often maligned for a reticence to engage dramatically, Fleming, in excerpts from favorites Manon and Der Rosenkavalier and Erich Korngold’s rarer Die Kathrin, all of which sit towards the still smooth center of her range, were inflected with as much pathos as any staged performance.

“Adieu, notre petite table” was both morose and ecstatic, intimate yet grandly scaled. More than anything, it demonstrated that though Fleming might not have fit perfectly into every role in every role she sang, the cool, plaintive, underlying sob in her timbre and attentive musicianship allowed an earnest and communicative telescoping of the standard Opera Emotions—Sorrow! Rapture! Joy! Rue!—that was and remains unique.

The Marschallin’s candid monologue, which remains putty in her interpretative hands, spoke similarly to those strengths. That this transmitted so easily over the airwaves is a testament to the technology the Met employed.

The afternoon was rounded out with some passable verismo highlights, “Io son l’umile ancella” and “Musetta svaria sulla bocca viva” from Leoncavallo’s La bohème, a blowsy “Over the Rainbow,” complete with scoops and interpolated high notes, and a Brahms Wiegenlied to lull us to sleep in the mid-afternoon.

Though the afternoon was meticulously programmed and staged, before the Arlen, Fleming addressed the virtual audience in a heartfelt speech about how much she and her colleagues miss performing for live audiences. It was a rare a glimpse of spontaneity and vulnerability on behalf of an industry that is bravely soldiering on as revenues hemorrhage and exposure dips. It was equally meaningful in contrast to the unexpectedly rigid, PBS telethon-style hosting of the normally fun and relatable Christine Goerke who provided introductions to documentary segments that broke up the program.

I find that recitals like these are usually the best benchmark we have to assess an artist at any stage in their career. Fleming has reached a status where an assessment of her performance involves much more than just an appraisal of her vocal state. Contrary to her new nickname in all the best ways, the necessary nuances of any conversation surrounding Renée Fleming seem very “diva” to me.

The concert will remain available for streaming until August 12. Tickets can be purchased for $20.

Comments