His repeat Broadway engagements are surprising to me, a devoted Broadway lover who nevertheless associates the term “contemporary Broadway musical” with “Remember that movie you sort of liked in 1993? What if it was longer and the characters sang?”

But however it happened, it happened. It’s 2020, Ivo’s the new Ethel Merman, and I caught a preview of his fourth Broadway show and first Broadway musical, West Side Story. The production is still a work in progress and undoubtedly will develop further before its official opening on February 20, but based on what I saw, I’m looking forward to revisiting it then.

First, what you knew just from looking at the marquee: it’s a dramatic departure from past productions. West Side Story has mostly resisted reinterpretation, I think mainly because the original piece is so well-made that there’s no real reason to tinker with it.

Because most productions tend to resemble each other, I’ve previously enjoyed the show less as a piece of drama than as a musical experience. It’s one of my favorite scores in any medium, with not a single “Little Lamb” or “This Was a Real Nice Clambake” to skip over, and the central roles offer singing actors rich musical and dramatic opportunities.

More so than many pieces that travel between the opera house and the Broadway theater, West Side Story feels to me like a consistently “serious” score. As evidence of its classical bona fides, the West Side Story suite is constantly programmed at various symphony orchestras around the country, offering audiences the distinct camp pleasure of watching a bunch of seated orchestral musicians in black tie shout “Mambo!” in unison.

This West Side Story is a ground-up rethinking of the sort I love best, where a central intellectual idea is combined with unexpected moments of theatricalized beauty. While not common, this style of staging isn’t entirely new to Broadway; for example, Daniel Fish’s intelligent reconsideration of Oklahoma! as a foundational text of white American cultural hegemony was a critical hit last season.

It remains shocking to see this sort of production in such a mainstream commercial environment, and I’m hopeful that we will see more directorial experimentation on Broadway in the future, alongside traditional revivals, of course.

Van Hove has worked in his typically minimalist mode to reduce and streamline West Side Story, eliminating many of what I had thought were essential aspects of the musical. This pared-down production may be somewhat distressing for West Side Story fans anticipating the various pleasures the show typically offers in abundance. “I Feel Pretty” has been cut, as has the “Somewhere” ballet (though the song remains).

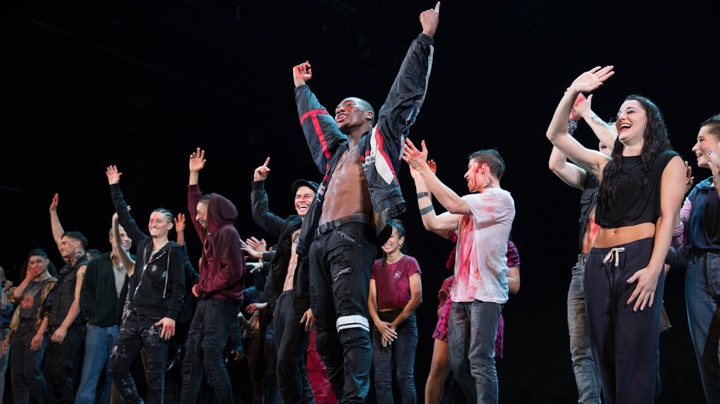

The book scenes race into one another with a frenzied pace that I found exciting and at times even stressful. The frantic tempo of the show, which here runs 105 minutes with no intermission, does not allow for the actors to make the individual impact they would in a more leisurely paced production, and some of the emotional beats that typically give West Side Story its power are yada-yadaed over in favor of other thematic concerns. But what remains is, I think, very exciting and unexpectedly contemporary in a way I wouldn’t have previously thought it possible for West Side Story to be.

As in many van Hove productions, the stage is dominated by an enormous video screen. The vast downstage expanse of the stage is bare and often completely empty. Characters come downstage to dance or fight, then retreat into small spaces far upstage or even offstage for warmer, more intimate moments which we see on the screen. The main stage space, like the long night time shots of empty city streets that sometimes play on the video screen, is dark and menacing, a place where violence could erupt at any moment.

The characters in this West Side Story are under constant surveillance. Everything is being recorded, everything is being streamed, and everyone is always camera-ready. The Jets posture and scowl in proscenium-high close-ups in the opening scene.

During the Quintet, we see a dozen characters going through their private preparations for the rumble in their own Instagram-curated offstage spaces before coming out to the main stage to unleash violence. The anti-cop message of “Dear Officer Krupke” is modernized through a devastating series of scenes showing the callousness with which violence is done to black and brown men by American law enforcement.

The intermediation of the camera makes Anita’s sexual assault exponentially more vivid and painful, calling to mind the horrific assaults that have been streamed on YouTube or Facebook Live in recent years. Here, the men who attack Anita are not just angry, they’re aware that the externalization of their anger is being broadcast for everyone to see. The effect is chilling.

The video is also innately distancing. We sometimes don’t know if scenes we’re seeing are being performed live or previously recorded, and, together with the frenetic pace of the production, the constant filming creates a certain homogeneity among the cast members.

The actors, most of whom were new to me, were more effective as a unit than distinctive as unique personalities. The two who stood out most were Shereen Pimentel’s gentle, delicately sung Maria and Isaac Powell’s posturing, sweet Tony. They seemed to move at a slower tempo than the other performers, just slightly separated in time and space from their contemporaries.

The production, interestingly, does not seem particularly interested in the tension between the Puerto Rican immigrants and more established Americans. This has odd side effects for those who are expecting to feel certain things during West Side Story, most notably that the traditional showstopper “America” isn’t a particularly memorable moment here.

I missed the chance for a star-making moment for Anita (Yesenia Ayala), but ultimately van Hove is less interested in the differences that separate the Sharks and Jets than in the monumental shared challenges their generation faces. As the repeated, synchronized movements of Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker’s choreography make clear, these kids aren’t particularly different from each other. They’re all mad, they’re all afraid, and they’re all facing a future that looks more and more like it will never come.

During “Cool,” as the male dancers play-fight and pose on the open space of the stage, we see a group of women on a screen in a confined space upstage, dancing with the same manic energy but without the space in which to unleash it.

And during “Somewhere,” the combatants stop fighting and hold each other in silent pairs as a rainstorm batters them, a moment of transfixing beauty after the visual overload of the fight scene. “Hold my hand and we’re halfway there,” Tony sings—and here, he knows that halfway there might be the closest they’ll ever get to the future they were promised.

The core question that interests van Hove here seems to be not “how can love overcome cyclical violence,” but rather “what does it mean to fall in love during the end of the world?” The act of loving another person, in the face of constant surveillance, fear of violence in public places, and anger at a future destroyed by the selfishness of previous generations, is an act of radical rebellion. It’s a small, hopeful, beautiful choice, but as Maria sings, it’s all that we have, right or wrong, what else can we do?

Maria and Tony find each other among the darkness and chaos. They pursue love with a manic optimism that defies the odds against them. When their love is destroyed, Maria wants to kill—wants to kill anyone—and we see why. She tried to create something in a world where only destruction is possible, and now she’s decided to get with the program and embrace the dominant paradigm.

I get the sense, after a dozen or so van Hove productions, that his primary interest is often not in characters or texts but in the audience itself. I was inspired by the way he reshaped Network, which I had thought of as a piece that blames the audience for its pedestrian appetites, as a plea for populist solidarity against the corporate elites who seek to control the world.

His The Damned dramatized how fascism is on the rise, not in the faraway past but now, in our countries, with our willing participation. In The Fountainhead, he showed us that it’s possible to turn our back to the ranting Howard Roarks of the world, leaving them alone in darkness to spout their nonsense without a platform.

I left West Side Story overwhelmed with empathy and sadness for the impossible situation we’ve left today’s youngest generations to deal with. They’re angry, and they have a right to be. As the Jets sing in “Gee, Officer Krupke”: society’s played them a terrible trick.

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Comments