Andermann is the veteran film producer who had the notion to assemble top-flight talent from the worlds of music and cinema for a generously funded film of Tosca. The action would unfold at the story’s specified locations (Sant’Andrea della Valle, Palazzo Farnese, Castel Sant’Angelo), and the film would be broadcast live to 107 countries. After a lengthy period of planning and preparation for this risky undertaking, the live broadcast took place in three installments over a weekend in July 1992, at the story’s designated times of day.

In a typical opera film, singers or actors mouth to a prerecorded soundtrack. A similar Tosca of 1976 (with the same Cavaradossi) had followed that game plan. Here, the singing was done live on the locations. The cast followed the Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale RAI and conductor Zubin Mehta via loudspeakers and television monitors kept from view of the cameras. Mehta, miles away, also conducted “live” while listening to the singers via headphones. After the live broadcasts, minor mishaps were edited out, the singing was perfected for posterity, and the episodes were stitched together for integral distribution.

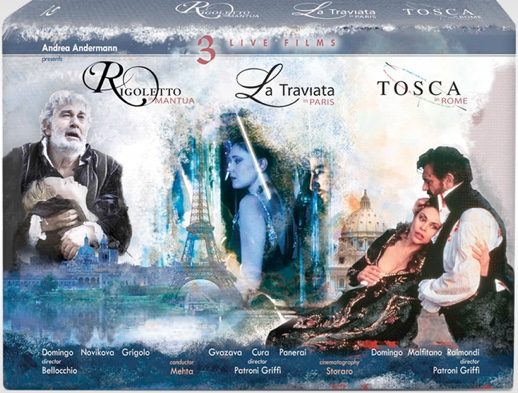

Tosca: In the Settings and at the Times of Tosca (unwieldy title, that) received a 1993 video release on VHS and laser disc. Its success and acclaim, including television awards in several countries, led to similar Andermann productions: La traviata in Paris (2000) and Rigoletto in Mantova (2010).

Andermann kept together most of his team over 18 years, beginning with Maestro Mehta and the RAI players. All three films were photographed by three-time Academy Award winning cinematographer Vittorio Storaro (Apocalypse Now, Reds and The Last Emperor). Director Giuseppe Patroni Griffi‘s death in 2005 put the third leg of the triptych in the hands of another distinguished Italian filmmaker, Marco Bellocchio.

Superstars Plácido Domingo and Ruggero Raimondi starred in Tosca but were absent from Traviata, Domingo by then being too old for the younger Germont and not yet covetous of the elder, Raimondi presumably being too much of a luxury for Grenvil. Both singers, now nearing 70, returned for the last film as Rigoletto and Sparafucile, respectively.

Naxos has collected all three films in a handsomely packaged set with a magnetic clasp, a 160-page book filled with photos and recollections (text in English and Italian), and a bonus disc with features adding up to 190 minutes.

The Tosca making-of is a retrospective affair dated 2008; those for Traviata and Rigoletto were contemporaneous with the films themselves. The documentaries will tell you everything you want to know and possibly more about the process of creating the films. We hear from Andermann, Mehta, Domingo and other singers, Storaro, Steadicam inventor Garrett Brown (who worked on Traviata), sound technicians, musical authorities including Philip Gossett, Puccini’s granddaughter Simonetta, a priest at the Sant’Andrea della Valle who was thrilled when those movie/opera people were gone…it is an exhaustive overview, often enlightening but perhaps to be enjoyed over time.

There is much in Tosca about eyes, but also much about hands. Scarpia sings that his hand awaits Tosca’s delicate one, and of her lover’s hands bound. Tosca sings of beseeching Scarpia with clasped hands, and of the secret hand with which she sought to alleviate miseries. The hands of Tosca arrange flowers (she carries them at her first appearance), execute dramatic stage gestures, commit violent murder. Cavaradossi mourns her sweet hands, pure and gentle. The enlightened Cavaradossi is first seen working with his hands, creating his art. A ring is the bribe that unlocks his hands to write. Scarpia’s hand signs the fraudulent safe passage, and he metaphorically holds the lives of others.There are many examples in Patroni Griffi’s film of the familiar story being directed in meaningful ways that go beyond coasting on visual splendor. The first that comes to mind is a little rhyme Patroni Griffi sets up on the “hands” motif. The bedraggled escapee Angelotti is behind a chapel grate, reaching through it toward Cavaradossi, imploring; we see the shot from both points of view. The decision that Cavaradossi makes in this moment will decide his fate. An echo comes later: the camera lingers on Scarpia’s hands sliding across the dinner table toward Tosca, imploring in another way. In both instances, the person being reached toward registers horror, indecision and a dawning awareness of consequences.

All three principal figures receive strong and persuasive characterization, and I have not seen their psychology and interactions handled better. This Tosca is spirited, high-strung, and childish. Her humor is “cute,” that of a young person–when she orders Cavaradossi to change Mary Magdalene’s eye color, she mimes dabbing at the painting. Once a temperamental squall has subsided, she has the wrung-out quality of a child who had been upset but will be on good behavior after reassurances. There is nothing arch or calculated about her. Her feelings are genuine, intense, primal.

Cavaradossi is much the stronger character, the adult in the relationship. Scarpia is a fascinating antagonist for them. Near the conclusion of the first act, he hovers over and behind the praying Tosca with what looks like real, unguarded tenderness, and draws ever closer to her. When Tosca leaves the church, this side of him vanishes. With a flip of the switch, he finds new vehemence for his remarks during the Te Deum. Both Tosca/Scarpia scenes are sexually charged, and the one at Palazzo Farnese is electric. When the bargain is struck, Scarpia lays a long kiss on Tosca, and her reactions are complex and disturbing, to her and to us. Revulsion does not appear to be one of the reactions. We may ask whether Scarpia himself is all Tosca is killing.

Tosca’s subsequent recounting of events for Cavaradossi, though factually accurate, has a flattened-out quality. The ambiguity we saw has been bleached out of it. Is she aspiring to Cavaradossi’s virtuousness, willing away recognition of her powerful attraction to the sinister, magnetic Scarpia? This Cavaradossi never for a moment believes he is going to be spared execution, or that Tosca will make it off that roof alive. His “Parlami ancor come dianzi parlavi, è cosi dolce il suon della tua voce!” is urgent and very sad.

Nothing Patroni Griffi finds is shocking, and nothing is inherently “right” or “wrong,” but he has made big decisions within a generally orthodox production, and what he has decided upon plays with power and conviction. Why is this so rare?

Catherine Malfitano makes an effective Tosca without having ideal equipment for the role, or at least without having completely worked it into her voice (she was singing it for the first time). She has a pretty middle register and some good chest tones, but often sounds whitened or puffed up, simulating Italianate grandeur. She compensates with a high-voltage personality and the right feeling, and is always interesting to look at–she actually has the irregular beauty of a stage idol of an earlier time.

Cavaradossi was one of Plácido Domingo‘s best and most frequent roles over many years. By 1992 he was deeper into Wagner, and it was getting close to time for him to set aside old standbys. The voice is bulkier, the tone less brilliant than in the 1985 Met video, with a tug on the top, but musical and dramatic responsibilities are handled with customary elegance and assurance.

The great performance is by Ruggero Raimondi, who is in good voice, is well recorded, and never oversells anything. Like all the best Scarpias, he knows the value of only hinting at menace. He is intelligent enough not to snarl and roar from the start and leave himself nowhere to go in the second act. The excellent Italian comprimari include a future Fiesco and Filippo, Giacomo Prestia, as Angelotti.

Television director Brian Large prefers to keep us very close to faces. There is some eccentric angling, providing good views of walls, ceilings, skies, and the principals’ dental restorations. In this as well the two films discussed below, subtitles are often helpfully shunted to the side so as not to cover faces or spoil compositions.

I had not seen any of the films in this box before receiving the set for review, and I finished Patroni Griffi’s Tosca believing Puccini’s opera a greater work than I had thought it to be two hours earlier. No higher compliment can be paid.The strong start raises expectations for the rest of the trilogy. Unfortunately, the magic does not return for Traviata in Paris, shot at Hôtel de Boisgelin, Hameau de la Reine, the Petit Palais and the Île Saint-Louis. One problem is that Traviata does not adapt as well to this cinematic approach. It is inherently stagier, with its primo ottocènto holdovers.

The viewer is keenly aware of artificiality when, for example, Patroni Griffi has no better option than to shoot a chorus of guests walking toward the camera in mass exodus, singing about how much they have enjoyed themselves at the party now ending. Traviata has a greater number of extended arias to deal with, and Patroni Griffi’s visual solutions to them are standard choices.

That aside, the director seems less inspired by this story and these characters. There are only flashes of what elevated the Tosca, and what remains to be praised is just a good filmmaker’s shrewdness. For example, “O mio rimorso” is literally a “cabaletta,” with Alfredo bitterly musing in profile, having boarded a horse-drawn carriage. It is a smart way around the staginess of the character standing and singing at length about what he is preparing to do.

All of this would matter less if the Traviata cast members had matched the artistry of their Tosca counterparts. Tall and attractive young Siberian soprano Eteri Gvazava had been singing with a small German company when Andermann handpicked her from among hundreds of hopefuls. Per his account in a New York Times article of 2000, he then kept his discovery out of contact with the world for six months of Italian lessons and rehearsals, and he predicted the film would catapult her to a marvelous career.

Despite the exertions of those six months, it is hard to imagine anyone who has heard Traviata adequately sung getting enjoyment from this Violetta. Tone is shallow; rhythmic points are neglected; phrases droop. For all the lessons, Gvazava pronounces the words as if uncertain she can do it correctly, and hoping errors will not be noticed. Much is unintelligible or swallowed up by the orchestra, and this is a wan, one-note heroine. The first scene leaves an especially bad impression. A fragile Violetta is plausible and perhaps desirable, but one who fails to stand out in the crowd at her own party is not.

Rolando Panerai had been singing professionally for over 50 years. One is inclined to be charitable in evaluating late-career Giorgio Germonts from veteran baritones who have given a lot, but this is not a good example. Panerai widens his eyes and shouts his way through the part, but is not really an angry or severe Giorgio Germont. The prevailing quality is blandness. There are several options for this character, and I am stumped as to which one Panerai was pursuing. He delivers lines very deliberately, as if he wants to be sure he is understood by someone transcribing at a distance. When he pairs with Gvazava’s mewling Violetta, his “too much” and her “not enough” make an unappealing combination.

José Cura‘s Alfredo is worldlier and more knowing than Gvazava’s Violetta, which cannot be right, but he is the principal trio’s standout by default. He was considered an exciting prospect at the dawn of the millennium, and may have been expected to carry the film. With benefit of hindsight, one can hear warning signs, and maybe they were obvious in 2000–his burly tenorizing is pressured and full-throttle, bespeaking technical contrivance. He is good-looking and a good actor, with a divo’s presence, but his brooding, intense Alfredo suggests a duded-up Don Alvaro.

The artfully directed final act is a remarkable 28-minute uninterrupted take from Garrett Brown and his Steadicam. We begin in Violetta’s more modest surroundings, and at first we see only Violetta’s and Annina’s hands in close-up. Dottore Grenvil enters and we never see his face either, only his hands. Grenvil carries out his examination, says comforting things, and tension is evident in his grip on a stopwatch. Gradually the women come into fuller view (the face of the young Annina, Magali Léger, is a terrific camera subject). The Germont men and the returning Grenvil are folded into the deathbed party with virtuoso fluidity.

This act is the visual high point of the film and should be seen by anyone with an interest in filmmaking technique. Brown is justifiably proud of his contribution; this veteran of 70 films considers the sequence a career high point. But with a musical performance more croce than delizia, Traviata in Paris offers little else beyond pretty scenery. There are a dozen better Traviata videos to see…or, more to the point, to hear. Even a sworn note-completist may be grateful for the traditional cuts.

Rigoletto in Mantova, filmed at Palazzo Te, Palazzo Ducale and La Rocca di Sparafucile, represents a partial recovery. Of the three films, it is the smoothest, with the highest level of technical polish (Storaro’s lighting is especially beautiful this time), but also the the most straight-ahead in its choices. Bellocchio’s work lacks the surprise of Patroni Griffi’s in Tosca and, to a lesser extent, Traviata. For long stretches, we see a routine stage production of Rigoletto transferred to unusual locations. This may have introductory-level appeal to someone coming new to Rigoletto, but only the interventions of the liveliest performers rescue it from dullness.Bellocchio is good with actors, and the Duke’s courtiers all have specific points of view. When Rigoletto pleads with and rages at them, the eye can wander from one face to another and take in different attitudes: cruelty, insolence, amusement, sympathy, shame, boredom. Gilda’s abduction, the business with the ladder and the blindfold, is better timed and more plausibly brought off than it usually is on the stage. Two scenes in which characters are spied upon through windows, and implausibly do not notice, may make a point. The observed characters are so lost in reverie that they are oblivious to danger.

At the time of this writing, Rigoletto remains a Verdi baritone role Domingo has not sung on stage. Perhaps singing it for the film convinced him it was not as congenial as others to which he has returned regularly: Nabucco, Foscari, Macbeth, Germont, Boccanegra.

Nevertheless, it hinted at the direction he would take in this decade, and a review of the performance applies to many of his others since 2010. This was once a magnificent voice, and he has more of it left than seems probable. He understands how the music is supposed to go; he knows what the words mean. Impressive singing alternates with blustery, strained singing. The dramatic performance is serviceable rather than finely detailed. There is a mass-marketed nobility more appropriate to kings, doges and gods; Rigoletto is deprived of shading. We may conclude feeling as though we should admire achievement and endurance (“At an age when…”) more than performance.

The other veteran, Raimondi, is credited with “special participation,” and his Sparafucile is a pleasant surprise. As recorded here, he makes more of low notes, never a strength, than I was expecting. He is again a clever actor, and he and the Maddalena, young Georgian mezzo Nino Surguladze, get a strong and interesting rapport going. Separated by 36 years, they would make a more likely father and daughter than brother and sister, and one can choose to view it that way–a warped mirror image of the father and daughter who observe them. Surguladze sings with authority and color and is a compellingly sexy figure for the camera, surely capable of luring marks into danger.

Russian soprano Julia Novikova was cast as Gilda shortly after her first-prize win in Domingo’s 2009 Operalia competition. Nerves are understandable, and hers is not a performance one would call “finished.” The Italian is muddy, a high note or two lands under pitch, and the phrasing needs sharper etching, but the vocal material is sound. She is not overmatched by Gilda as the previous film’s soprano was by Violetta, nor is so much of the opera’s weight resting on her; she can secure a draw. In dramatic terms, she is a satisfactory standard Gilda, with an accessible blond prettiness reminiscent of Michelle Williams’s.

Vittorio Grigolo was in 2010 another talked-about tenor who may or may not turn into something, and he has since cemented his status as a headliner. He convinces as the vain, immature, sexually harassing Duke of Mantua, and he can wear a puffy shirt. His relaxed, confident singing, with a pleasant, sun-dappled tone and quick vibrato, seems part of a package that would make him irresistible to the sheltered Gilda. Mehta’s brusque conducting keeps him coloring within the lines.

Mehta contributes to all three films what is needed above all: a steady hand. I find his approach more apposite in Puccini than in middle Verdi, but each time he gets an attractively burnished, weighty sound and holds singers and orchestra together in challenging circumstances.

Performances within collected sets, whether sets of Mahler symphonies or of Italian operas, rarely are of even quality across the board, making it difficult to render a verdict. Tosca in Rome (as it has been more concisely renamed) is the urgent recommendation, an outstanding filmed opera that wears its 25 years lightly. Traviata in Paris and Rigoletto in Mantova are, respectively, very disappointing and pretty good follow-ups. Neither would be my first choice for the opera under consideration.

Naxos’s box is attractive in presentation, with generous and interesting supplemental material. Ultimately, the call may come down to how intrigued someone is by the novelty of Traviata and Rigoletto as cinematic experiences, photographed by great technicians from another art form, separate from purely musical matters.