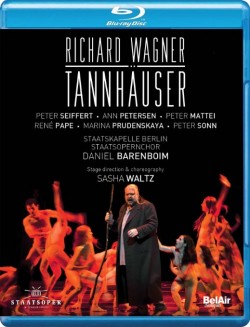

One wonders what he’d make of Staatskapelle Berlin’s 2014 production, now on BelAir Classiques. Director Sasha Waltz’s sweaty pileup of writhing bodies in the opening tableau serves as the jumping off point for a fully choreographed opera in which dancers weave around and through the scenes with sweeping gestures, arresting poses and sometimes sophomoric mimed responses to what’s being sung.

Waltz has done such work before, earning positive notices for adaptations of L’Orfeo, Dido and Aeneas and Berlioz’s Roméo et Juliette. Wagner proves a thornier task: The abstract movements and updated mid-20th century setting (a nod to the company’s temporary quarters in the Schiller Theater) strip away symbolic points of reference without really illuminating the clash between the sensual and the spiritual or other layers of the drama. Particularly busy moments, such as the first act scene with the Landgrave’s hunting party, almost veer into self-parody.

The mise-en-scène depicts the song contest on the Wartburg as a hedonistic tie-and-tails gala, a concept that obscures Wagner’s overt nationalism, with its nod to battles for the majesty of the German realm. Instead, male partygoers swoon as Wolfram sings of the pure courtly ideal of love and the ladies lift their gowns and shake their breasts to Tännhauser’s increasingly enthusiastic paeans to sensuous pleasure. By portraying the title character as a kind of polymath who presages the sexual freedom of the 1960s, Waltz breaks away from the work’s plodding earnestness but doesn’t inject enough dramatic substance to contrast with the opening act’s Venusberg scene.

There are some striking stage pictures of grey-clad pilgrims in fog-filled valleys, and of the saintly Elisabeth’s body being covered with leaves that have sprouted from the Pope’s staff at the very end of the opera. The Venusberg scene is a titillating pageant in which some 20 nearly naked dancers cavort and freeze in poses within a white tube-like structure that could have been inspired by a college term paper on dream analysis.

It’s left to the vocalists and Berlin orchestral and choral forces led by Daniel Barenboim to provide most of the interpretive substance. Barenboim fuses the extended Paris ballet music on to the standard Dresden edition of the opera — an imperfect marriage made better by his careful attention to the chromatic palette and the impressionistic aspects of the bacchanal.At 62, tenor Peter Seiffert struggles with the title role’s high tessitura more than on his Teldec set with Barenboim but progressively adds heft and shading to the interpretation in the final two acts. His Rome narrative has a detached, third-person quality that abruptly veers into deep despair at the recollection of being denied pardon by the Pope, making the character seem quite contemporary, as it he’s grappling with issues that could require an analyst.

Peter Mattei’s Wolfram is done up as a bit of a nebbish in suspenders and shirtsleeves and subjected to some odd tai chi-like blocking during his song to the evening star. No matter. The baritone is tender and noble, struggling to comprehend the peevish Tännhauser’s internal landscape and keenly aware that he can’t measure up in Elisabeth’s eyes. René Pape is a dignified Landgrave Hermann, wrapping his impressive bass around the welcoming aria “Gar viel und schön” and infusing every phrase with meaning.

The women are less vocally satisfying. With an assertive top range, keen dramatic instincts and movie-star looks, Danish soprano Ann Petersen ably navigates “Dich, teure Halle” and Elisabeth’s Act 3 prayer but doesn’t temper the portrayal to deliver enough depth of characterization. Russian mezzo Marina Prudenskaya’s Venus is intense, with a fast vibrato and slightly tart tone that won’t be to everyone’s liking but is certainly attention-grabbing. Perhaps it’s the quality of this recording, but she sounded more sensual in the role on Marek Janowski’s version for PentaTone. Solid contributors in lesser roles include Tobias Schabel as Biterolf and Sonia Grane as the shepherd.

Barenboim takes a fleet, no nonsense approach that spotlights the music’s folk-like qualities and flowing phrases without putting a particularly distinct interpretive stamp on the proceedings. The Staatskapelle Berlin sounds in fine health, a few intonation issues notwithstanding, with the violins excelling in their difficult second act passages and the brass sturdy and majestic (eight horn players get a collective cameo, walking across the stage at the conclusion of the first act as the hunting retinue gathers). The chorus admirably captures Wagner’s desire for the pilgrims to sound as if approaching slowly from a great distance.

Wagner was never completely satisfied with Tännhauser, and his efforts to adapt it to Paris with Venus’ court proved a fiasco. This odd production may try to capture the composer’s notion of gesamtkunstwerk but is most effective when there’s a minimum of stage business, allowing the music to stand on its own. On those merits, it’s a worthy contender among the DVD releases.