Few truly important operas of that century have been less well treated by vicissitudes of time and taste than Weber’s seminal Der Freischütz. This magnificent early-Romantic score, generously served on recordings of the LP era, is yoked to a libretto that can seem hopelessly quaint and hokey when staged “straight,” but does not easily update. A young assistant forester’s engagement to his mentor’s daughter is riding on his marksmanship, which lately has grown unreliable. He is offered false salvation by a sinister colleague, who lures him into a satanic pact involving magic bullets. Real salvation is granted by a deus ex machina holy hermit. Along the way, there are waltzes and beer, hallucinatory chills in the Wolf’s Glen, and a great deal of spoken dialogue.

Outside of German-speaking territories, Freischütz has become a rarity. When it was last seen at Lincoln Center, The Godfather topped the box office, and the Watergate was as yet unburgled. Covent Garden has offered fully staged performances more recently, but Karita Mattila was a promising new face at the time, and Margaret Thatcher a withholding old one.

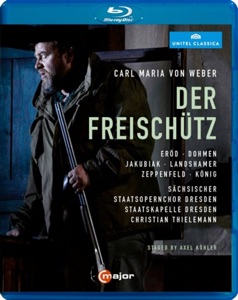

A new DVD from C-Major documents a 2015 Dresden State Opera production with perhaps the finest German conductor of his generation leading the Staatskapelle and a capable cast. The booklet reminds us that Dresden has hosted more than 1,500 performances of Weber’s Singspiel, more than any other city in the world. The new release would seem to be just the ticket for anyone who has not seen Freischütz staged recently and has desired its return. Unfortunately, while addressing the deficit, it also may curb the desire.

German countertenor Axel Köhler made his singing debut nearly 30 years ago in a Handel production by Regietheater eminence Peter Konwitschny. Köhler himself took up directing at the close of the 20th century, and he has been at it now for approximately the length of Calixto Bieito‘s career. In broad outline, his Freischütz suggests Bieito with a low-grade fever.

Most of the opera is staged in the bombed-out ruin of a once-grand house in some war-torn 20th-century province. The natural beauties described in the text are nowhere in evidence, and even the shooting contests take place indoors. Costumes span post-Weimar eras. The villagers are hostile and prone to violence. The first-act waltz is a fistfight between Max and Kilian that ignites a free-for-all. Old Kuno the head forester is the irascible leader of some paramilitary organization, making his entrance surrounded by underlings with guns at aim. “Oh, diese Sonne!” wails Max, as Fabio Antoci‘s lighting downshifts from “murky” to “coal mine.”

When Max shoots the eagle at Kaspar’s instruction, Köhler unwisely has a prop eagle come plummeting down (presumably the bombs took out the roof of this place), like something out of a sketch-comedy show. The audience’s derisive laughter is honestly reproduced. Kaspar later cuts off one of the eagle’s wings and waves it around. Our bad guy keeps busy with that knife; he also drags an unconvincing corpse into the Wolf’s Glen and decapitates it.

An unscripted mute character, a limping maid well played by Anna Katharina Schumann, appears to be in league with Kaspar and his offstage puppetmaster Samiel (or possessed by Samiel?), but suffering over it. She is exposed and driven out in the final scene. Such vestigial ideas as the director has are clustered at the beginning and the end. What comes between, especially the feminine diversions of Agathe and Ännchen and the bridesmaids, would fit into the hoariest traditional staging, but for the drabness of the surroundings.

This is less of a production than the sketches for one, and while I never advise it, this time you could judge it from still pictures. It displays grimness and violence in an empty-headed, superficial way, as if just putting these qualities on the stage is a bold corrective.

The singers who can act well come through with some personality and dramatic intention; the less gifted ones look at the floor or the maestro. The Max, German-Canadian tenor Michael König, is in the latter category, but one is inclined to accentuate the positive. He makes a grainy sound that cannot be called conventionally beautiful, but in his use of that voice, there is a forthright and intelligent performance with the heft of a promising Wagnerian. If his apparent unease on the stage is characteristic, one hopes he overcomes it with experience. If it is related to being filmed in this production, one’s heart goes out to him.

American soprano Sara Jakubiak replaced a colleague late, and perhaps these are not ideal circumstances in which to make her first acquaintance. As noted above, her scenes are directed with indifference, but there is not much to respond to in her mewly, monochromatically forlorn Agathe. She and her irritable, hulking Max will make a terrible life together. Somewhat better is the Ännchen of Christina Landshamer, who gets no more help from the staging but fitfully suggests a young woman whose chipper demeanor is a shield in a bleak world. It is not the worst solution to what can be an annoying soubrette role.

There are better-known and better-publicized German basses than Georg Zeppenfeld, but while I watched and listened to this, I wondered if there are any better ones. I have previously seen Zeppenfeld make a great deal of such major-minor parts as Sparafucile, König Marke, and Pogner. Here, in a good showcase for his voice type, he is as commanding a musical and theatrical presence as I had hoped, pouring his arresting squid-ink-colored tone into Kaspar’s machinations, and physically resembling a younger Max von Sydow (circa Winter Light). The props he has to drag around may be laughable, but he never is.

Four smaller male roles are in good to excellent hands. Veteran bass-baritone Albert Dohmen makes a solid contribution and is just vocally craggy enough as Kuno. Baritone Sebastian Wartig, only 26 at the time, sings the brief role of Max’s rival Kilian so heroically and with such beautifully inflected words that he seems out of step with the juvenile stage business he has to carry out. Bass Andreas Bauer, the Hermit, is in the tough spot of showing up at the tail end of a show that has been well served for lower male voices, but he is shrewdly cast. He brings a new and distinctive color to the vocal canvas and suggests hard-won wisdom and authority under the layers of grime.

Finally, Adrian Eröd, not only a scrupulous musician with a fine voice but one of opera’s cleverest actors, is a luxury as Ottokar. Eröd has demonstrated many times that he can think on stage and make a character’s inner life read vividly, and he does so again here. His Ottokar for Köhler is a smug fascist on the upper middle of the power ladder, aiming higher. He is accustomed to traveling places and patiently bearing ceremonies he considers beneath him. In reversing his decision on Max’s fate, he knuckles under to the Hermit (here, perhaps, a long-absent superior Ottokar did not expect to show up and overrule him), but he lets us see the dissatisfaction behind the capitulation. It is a brilliant cameo.

Christian Thielemann‘s conducting comes at Weber from the other end of Romanticism, emphasizing the link to Wagner and Bruckner in a smoothly blended, big-boned reading, with phrases not classically and crisply “attacked” but bubbling up and gliding out of what preceded them. The Staatskapelle Dresden sounds slightly below its considerable best. Under the direction of Jörn Hinnerk Andresen, the Staatsopernchor Dresden makes a glorious showing. Their ecstatic response to Agathe’s survival in the final scene is a hint of everything Freischütz should and can be.

“If everything was awry visually, there were some few auditory compensations,” wrote David Hamilton of that long-ago Met Freischütz, and I might have saved you some reading by simply stealing his line for the Dresden one of 44 years later. I do not doubt that this undertaking began as a sincere attempt to make Freischütz “stageworthy” in the present day, but the result is that of very good individual performances trapped in an unworthy and, one hopes, unmemorable frame. Samiel’s amplified offstage drone in the Wolf’s Glen sounds less frightening than bored. Taking in this remarkably dull show, one’s sympathy is for the devil.

Comments