A while back I joined a closed group on Facebook called “The Beverly Sills Crazies.” I can’t recall how I found the first posting on my feed but they seemed like a fun bunch and I’m a great accumulator of digital pictures of set and costume designs. It’s been dubbed my “Opera Porn” collection. When knocking on the door to be let in I did feel it necessary to be frank in that, although I appreciated Ms. Sills and certainly enjoyed her work, I was not “crazy” for her. (My secret heart belongs to another diva.)

I was nonetheless received into the fold with a formal posting on the page and many joyful welcomes. It is, by far, the most well-behaved and pleasant group of people I have ever encountered on the interwebs. They luxuriate in their Beverly exclusively with remembrances, photos, keepsakes and the occasional porcelain figurine. They continue to show their devotion to her through their unstinting good humor and camaraderie.

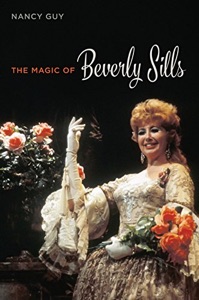

A few months ago a book starting popping up in the “Crazies” feed entitled The Magic of Beverly Sills. I immediately looked on it with disdain and could well imagine the type of corpulent, self-published, valentine it must be. As I scanned its Amazon page I looked to see if it came with a complimentary pair of rose-colored glasses.

I read so many postings on the “Crazies” page from then on, the tone of which of which hovered between “Hosannah!” and “My life is complete at last!” that I become curious. Then I happened to notice that the tome was published by the University of Illinois Press, part of their “Music in American Life” series of more than 200 volumes on music and musicians, many of which I had already enjoyed at my local library. I then proceeded to dismount my very high horse and order myself a copy.

When it finally arrived I was taken not only by the beauty of its printing and but by the evident quality of its paper and binding. It was a most substantial book, as I leaned when I inadvertently dropped it on my foot.

The author, Nancy Guy, is an Associate Professor of Music at the University of California, San Diego. She has written two previous books, Peking Opera and Politics in Taiwan. She is also a Beverly Sills fan. It’s this expression of fandom and the way it influences people’s lives that is part of the actual sociological study contained in the pages of this book.

Ms. Guy takes the introduction of the book to discuss why she felt compelled to study Sills, upon learning of her death and having not listened to her recordings for many years, and the notion of being a ‘”fan.” Fandom, it seems, is heavily discouraged in academia because of its lack of analytical objectivity. She also reveals that many of the books written about opera purposely minimize descriptive accounts of singers in performance in order to keep what might be viewed as, the irrational exuberance of the author “closeted.” A few works do address opera fandom head-on, e.g., Wayne Koestenbaum’s The Queen’s Throat.

There’s also serious discussion of what “magic” really is. This title that I had originally scoffed at was, no doubt, prompted by something Tito Capobianco, Sills’ longtime theatrical director, said during an interview with the author: “Be courageous and accept the fact—magic exists.” Indeed it does in this context because I’m certain every single person reading this reivew had their life touched, altered, or even fully derailed and course changed by encountering an artist in performance.

Ms. Guy goes into detail about what made Sills a “magic” performer, recounting reactions of people across an extraordinarily broad socio-economic spectrum who discovered their love of opera and singing through her. Surprisingly, since we all know how potent Sills was on stage, many of them were first drawn to her from appearances outside the theatrical operatic experience. Imagine then what seeing Sills in her element must have been like for these already curious pilgrims! Their memories are eloquent and quite touching in some cases.

There follow a few chapters on Beverly Sills’ progress and development as a student and performer and she was making a professional living at an uncommonly early age. There is very frank discussion about the condition of her voice when she reached the height of her fame. Both the author and her interviewees are in agreement that by the time Sills was recording the majority of her roles it was her dramatic flair and vocal bravado, not the voice per se, that were the main factors in their enjoyment.

Excerpts of reviews, both good and bad, are included with performance history, with none more amusing than the retraction Harold Schonberg, writing for the New York Times, ended up having to publish after characterizing Ms. Sills first performance in Roberto Devereux “as a specimen of bel canto singing it was, unfortunately, far wide of the target.” A month later, after being deluged by angry mail with accusations of all sorts—including”being prejudiced in favor of That Other Woman (Joan Sutherland)”, he was forced to reconsider.

I was surprised that there wasn’t more mention of Estelle Liebling’s training since Ms. Sills was singularly unique in her pedigree of being probably the last great singer in the line of teachers stretching all the way back through Mathilde Marchesi and Manuel Garcia. Certainly Sills’ iron-clad technical skill wedded to her determination were major factors behind a career that started in her teens and went all the way until she was 51.

Also surprising is the insight from Capobianco that Sills never suffered any stage fright, as becomes so common in many big careers, and that she often gave her best performance on opening night. To this end the author compares in the chapters “Hearing Intentionality” and “Hearing Action and Reaction” the pirated recording from the New York City Opera’s premiere of Anna Bolena with Sills’ own annotated score, as well as recollections of those who saw and participated in the performance. The alignment of these various components is made clear to stunning effect and insight.

The assemblage of all of this data surely took years of work and Ms. Guy devotes a chapter to discussing the fans who helped her put together the pieces. Their stories of devotion and collection are told with tenderness and a complete lack of condescension on the part of the author.

There’s also discussion of what “presence” mean,s both from an anthropological standpoint and how artists bond us as audience members during performance through what amount to a kind of mass mesmerization. She also touches on those who are completely impervious to these spells.

Admittedly it might have been more fun to have read a juicy, backstage, pearl clutcher but that wasn’t the intention of this book from the start and Ms. Guy is very clear about the story she’s going to tell in the introduction. This is a serious academic study which, when necessary, adopts a dry, analytical tone.

The Magic of Beverly Sills is a fascinating read with great respect for its subject as an originator of a real and yet unquantifiable magic. I hope for more books of its type regarding singers, their careers, and the impact they had on their public and the society around them. In fact, this “crazy” is eager to pre-order The Glory of Leontyne Price.