Sir Andrew Davis led a detailed and fascinating account of this difficult score, and the Lyric Opera Orchestra responded with some of its best work of the season. The brass and string sections in particular played with great precision and cleanness. Davis clearly wanted the audience to hear the lyric beauty of Berg’s mesmerizing score, yet did not stint on the powerful cacophony of the emotional climaxes. I have never before heard the aching beauty of the strings that begins Marie’s “repentance” scene in the third act, and all the music between scenes was played with subtlety and nuance.

McVicar moves the setting to World War I era Germany, and the setting by Vicki Mortimer works wonderfully. Centered by a large war memorial statue, each scene is delineated by two stage-wide, bloodied curtains that move at varying speeds, always matching the movement of the plot as they reveal the various scene locations. Props fly in and out—I was particularly taken with a giant magnifying glass that made the Doctor’s office grotesquely frightening.

There is a huge bicycle contraption for the Captain, and a huge cart that Wozzeck struggles to move to carry kindling with his friend Andres, and this cart will make another appearance later in the play. More on that in a bit.

McVicar tells the story vividly, with particular emphasis on the unending cycle of poverty that torments Wozzeck. Franz Wozzeck, a poor soldier, is tormented by his paranoid Captain and is the subject of gruesome medical experiments by The Doctor, his only source of income, all of which he gives to his Marie to support their out of wedlock little boy.

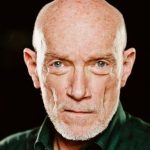

The ensemble cast is excellent from the smallest roles to the largest. Polish bass-baritone Tomasz Konieczny is harrowing in the title role, pouring forth dark and foreboding tone. He stunningly portrays the arc of Wozzeck’s mental decline with subtle vocal and physical choices. There was something Shakespearean in his portrayal, reminding one of Othello’s jealous frenzies, especially with his cry of “Blut, blut, blut!”

Soprano Angela Denoke was a superb Marie, trapped by poverty and considered a whore by her neighbors for bearing her bastard son. She sang with clarion tone and brought beauty to even the most shrill of Marie’s outcries. She was entirely convincing in her motherly love, her lust for the Drum Major, and her terror in her final scene with Wozzeck wielding his knife, and very touching in the scene where she reads the Bible in a futile attempt at repentance.

Gerhard Siegel is an experienced Captain, and navigates the treacherous vocal lines with ease as the music jumps from octave to octave without transition. Brindley Sherratt has something of a John Carradine profile as the cruel Doctor, and sings with authority. David Portillo’s Andres starts a bit underpowered, but grows in vocalism as the opera moves along. His is a very sweet tenor, a splendid David in Lyric’s most recent Meistersinger.

And Wozzeck’s son, played brilliantly by child actor Zachary Uzarraga, provides an overwhelming image at the very end of the opera, perhaps McVicar’s finest moment. After the children have told him of his mother’s death and they run off to see her body, the boy does the usual “hop, hop” business with his hobby horse. But then, he quietly abandons the horse and walks toward the same cart contraption that had been Wozzeck’s burden in his early scene with Andres.

His tiny arms go through the rings, and he struggles to drag the cart offstage as the lights black out. The effect was absolutely chilling. Here, McVicar makes clear the hopeless nature of the cycle of poverty repeating itself for generations. Life father, like son.

Stark and angular lighting by Paule Constable and Ms. Mortimer’s costumes gave excellent support to the proceedings, as did the Lyric Opera Chorus. There are only a few more performances of this opera, and I urge everyone in the Chicago area to try to attend. This was one of those performances that remind you of the power of opera to move us and stimulate our ideas.

Photos: Cory Weaver