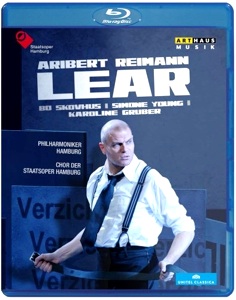

Aribert Reimann’s 1978 opera Lear, based of course on Shakespeare’s titanic tragedy King Lear, is a major achievement in modern operatic scoring. In a DVD

from a deeply interesting 2014 production from Staatsoper Hamburg, we find a fascinating if flawed direction by Karoline Gruber, propulsive and insightful conducting from Simone Young and a breakthrough performance by Bo Skovhus in the title role.

Shakespeare’s Lear has been an important part of my acting career. I’ve had the great good fortune to perform in eight productions of King Lear (three Lears, two Fools, Gloucester, Albany, and the Duke of Burgundy) and the title role contains such depth and complexity that I’d love to play it again and again. I had real concerns about how this astonishing drama could be adapted into an operatic form.

But Reimann (whose wonderful Medea I reviewed for this site a few years back) is singularly capable of making music that is absolutely reflective of the emotional and passionate lives of his characters. It’s not pretty or melodic, but neither are the harrowing events of King Lear. The libretto by Claus H. Henneberg does a splendid job of streamlining the story while losing nothing of Lear’s descent into madness and his redemption through his daughter Cordelia’s love.

Reimann and Henneberg make a specific choice regarding the mysterious, truth-telling Fool character, here played with remarkable physical grace by actor Erwin Leder. In the play, of course, the Fool is an important character, the only one who tells Lear the truth without fearing consequences. In the opera, no one but Lear sees the Fool. He hovers about, speaking as if inside Lear’s mind.

And in the end (perhaps a nod to the notion that Shakespeare cast the same actor as the Fool and Cordelia), the Fool dons Cordelia’s clothes and becomes her in a haunting and moving fashion, as the singer playing Cordelia slowly dies, bending over a coffin. Lear himself puts on her clothes at his end, and the final blackout finds him standing in her dress with an expression of euphoria.

The major misstep in the production (and I can’t be sure how much of this is Reimann or the direction of Gruber) is that Goneril and Regan are drawn as completely cartoonish villains. This notion haunts many poor productions of the Shakespeare—if we can’t believe that Goneril and Regan make a reasonable choice to drive Lear’s train away, we can’t believe in the shock Lear feels at their betrayal. If the two daughters are just eeeeeevil, as they are portrayed here, the tragedy becomes Disneyesque and Lear’s plight completely unmoving.

In the first scene of the opera, when Goneril and Regan are called upon to make speeches expressing how much they love their father, they must make some attempt at being convincing or else Lear just seems stupid for not recognizing their duplicity. And Lear may be mentally shaky, but he is not stupid. Goneril’s “drama queen” music, followed by Regan’s semi-hysterical coloratura in this scene, work directly against the drama of a great king’s fall.

The Gloucester subplot, paralleling Lear’s fall, is finely played, though Lauri Vasar is far too young for the role of Gloucester. His two sons, the bastard Edmund (played with appropriate bluster and lust for power by Martin Homrich) and the legitimate Edgar, a haunting Andrew Watts, are well drawn characters. Watts starts as a tenor, then switches to countertenor when he disguises himself as the mad Poor Tom. This effect is marvelous.

The famous eye-gouging scene, where poor Gloucester is blinded by Regan and Cornwall, is as ghastly here as it is in the play, and the metaphor of Gloucester only understanding the truth when he cannot see is just as moving. And the gripping scene on the heath when Gloucester encounters the mad king is deeply moving: “It is the time’s plague when madmen lead the blind.”

Skovhus is simply splendid throughout, doing some of the finest, most passionate acting of his career. He sings with a remarkable palette of vocal colors and moods, and his performance is always authentic and painfully truthful.

Reimann’s opera ought to be performed more often. Though it’s undoubtedly hard to watch and sometimes musically jarring, it also has moments of surpassing beauty. I’d love to see a variety of productions of the work, from full period to post-modern. I think Gruber’s production takes too light an approach to the piece, but it nevertheless contains profound and stunning visual imagery.

Comments