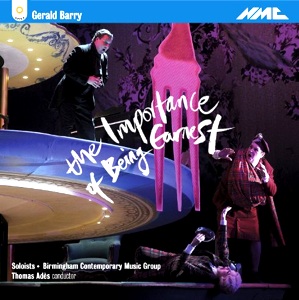

Before this recording arrived in my mailbox, I: ( a) didn’t know there was an operatic version of Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, one of my favorite plays; and (b) was unfamiliar with the works of composer Gerald Berry. After several hearings, I’m still not convinced that there is an operatic version of Earnest. Barry has created what I would call a narrative set to a series of sound effects. Now many of these effects are clever, occasionally amusing, and purposely bizarre, but they rarely seem to fit the brilliant verbal wit of Wilde’s original. I kept thinking that, if Lulu was a comedy, it would sound a lot like this.

The piece opens with a noisy and tonally unpleasant “overture” that is a crazed piano riff on “Auld Lang Syne” (which song recurs later in the piece). Having stifled my urge to toss the CD out the window during this aural assault, I settled in to hear the rest of the 80-minute work. Now let it be said that there are numerous moments of musical humor in the piece, including references to Psycho and breaking dishes throughout the Cecily-Gwendolen tea scene. But the majority of the musical choices are noisy and jarring and, well, loud, especially in the irritating brass sections.

The vocal writing jumps about wildly from a blustery bass as Lady Bracknell (who completely ruins the famous “A handbag?” line by pounding it so hard that it seems almost choked), Jack and Algernon leaping into frequent falsetto, and a stratospheric tessitura for Cecily Cardew that even the fine singing actress Barbara Hannigan cannot make comprehensible. Barry seems almost purposely to be obscuring Wilde’s lines, thus crushing most of the comedy. When the words are understandable, usually when the singers are speaking in robot-like rhythms, the wit seldom lands. For instance, why make the Cecily-Gwendolen confrontation difficult to understand by having them speak their lines through megaphones?

I have a strong feeling that this piece would work better in the theatre, where the singers’ expressions and reactions might illuminate some of the odd effects one hears on the CD.

The cast works gamely amid the virtually impossible vocal lines. Most successful is mezzo Karolyn Karolyi as Gwendolen, who brings some real vocal beauty to the proceedings. The lower voices were at an advantage here, as they were much more comprehensible; therefore, the Algernon of baritone Joshua Bloom and the Miss Prism of contralto Hillary Summers worked well. The most impossible task fell to Hannigan—Barry has done her no favors with pitches nearing “only dogs can hear” frequencies, though she strides mightily to use her snapped end consonants to help the audience understand. Alan Ewing is far too heavy-handed as Lady Bracknell, his gravelly bass sounding throaty and sometimes strained. All the while, Barry seems to be much more concerned with making clever instrumental effects than with language or believable characterization.

Thomas Adès does a very fine job of leading the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group through the roller-coaster score. There are some interesting instruments in use here—I think I heard both a kazoo and a penny whistle employed in a very effective wind effect. I found the brass playing consistently too loud throughout, but I can’t tell if this is an issue with Ades or with the balances struck by the recording engineers.

Barry’s work is very playful and inventive, but does not serve Wilde’s wonderful parade of sparkling verbal repartee. This score seems much more appropriate to the work of a modern playwright—Beckett, perhaps?

Comments