The opera Oscar begins with Wilde taking a curtain call at the premiere of The Importance of Being Earnest. The wheel of fortune begins to turn and the scene changes: Wilde is hounded by minions of the Marquess of Queensbury until he is forced to find shelter with friend Ada Leverson. All this drama is for the sake of Wilde’s love of Queensbury’s son Lord Alfred Douglas (“Bosie.”) As Wilde descends from fame to infamy, he becomes a Shakespearian tragic hero. The wheel of fortune moves quickly, and the curtain falls on the first act with justice not being served (staged a bit obviously in a circus milieu) and the hoosegow looming large for our hero.

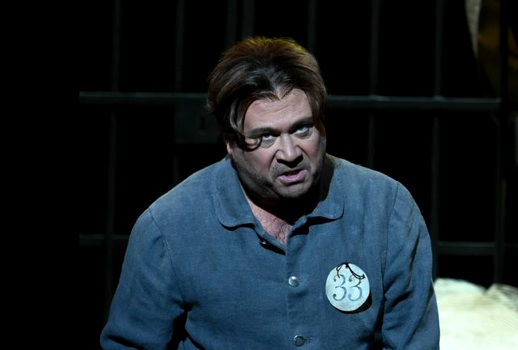

Act two finds Wilde incarcerated in a Victorian gaol, serving out his sentence for gross indecency with hard labor. Our butterfly beats its wings against its grim cage, while sadism and death (not to mention the spectre of Beethoven’s Fidelio) dance mockingly about. Amidst such incivility, however, Wilde finds redemption. “I found pity”,” Wilde tell us. Our tragic hero is reformed and released from prison. Thus, while Wilde dies a few short years later a broken wit, he perhaps… just, perhaps, dies a better human being.

As the opera ends, Wilde is inducted into the pantheon of artistic greats. He appears before the assembled audience and drolly admits: “For myself, the only immortality I desire is to invent a new sauce.” The aforementioned audience exits with a much-needed chuckle.

Still there were many attractive musical touches in this score. A favorite of this reviewer’s was the recurring butterfly buzz so reminiscent of Ravel’s Musique d’insectes (L’Enfant et les sortilèges). Conductor Evan Rogister milked the music for every scintilla of enchantment it had to offer.

Director Kevin Newbury thoughtfully realized the drama with more than a few inspirations: dialects descend from posh to poor as Wilde fruitlessly searches for a room at the inn; at the end of Act one, prison bars rise and engulf Wilde like the fires of hell.

Daniels conquered as Oscar Wilde. He’s onstage for well over two hours: “tour de force” doesn’t begin cover it. Daniels’s Wilde is a steel green carnation, at his best in the aria “My sweet rose,” the most memorable tune in the opera. This was simply great performance.

Reed Luplau danced the many incarnations of Bosie exquisitely. In the opera, Bosie is a silent role, conjured by Wilde’s psyche, who becomes siren and fury, harpy and succubus. In short, upon Bosie, a character given no voice of his own in the opera. is projected all of Wilde’s baggage—so much so that Bosie even assumes the guise of porter and bellboy at one point).

William Burden portrayed Wilde’s friend, influential businessman Frank Harris. He is a national treasure. How many times have I seen this artist over many years, and how many times has he always delivered the goods? Every time. Burden knows his craft, his English diction was flawless and an audience can always rely on his turning in a thoughtful performance. Bravo!

Heidi Stober‘s pert soprano made Wilde’s friend Ada Leverson all the more likeable. We would like to hear more from Stober in the future, in a more prima donnaesque role. Actually Stober IS the prima donna of Wilde, technically. Since Leverson is the only female character in the opera. Leverson is also the only person in the opera who seems to have it all “together”, fulfilled—in both traditional and nontraditional Leverson was a mother, a writer, an all-round interesting person it seems.

Baritone Ricardo Rivera was memorable as Thomas Martin, prison guard with a heart of gold. Bass-baritone Wayne Tigges impressed as sadistic prison warden Col. Henry P. Isaacson, a cameo star turn straight out of Wozzeck. Finally, Jared Ott showed star quality as Prison Infirmary Patient #1. Expect him to go far.

Photos by Kelly & Massa.

Comments