With the help of our friends at ArtHaus Musik, the Deutsche Oper Berlin have really been emptying out their archives and that’s certainly all for the good. What we have here is a real curate’s egg however in a DVD

of Boris Blacher’s opera 200 000 Taler. Blacher, who was born in 1903, initially studied architecture and mathematics before turning his attentions to composition and teaching. He lost his first professorship in Dresden after being pronounced a composer of “degenerate” music by the National Socialist Party (damn those Nazis!) He took up teaching again after the war in 1945 as the Director of the Music Academy of Berlin.

Blacher’s music is typical of the post-war Berlin school and he was considered its central figure by many. His colorful orchestrations, almost French in style, might sound a tad sterile held up next to Debussy or Ravel. He also experimented with “Variable Metrics” in the sense that he applied mathematic formula to repeated musical forms.

For those among us who wait for an outpouring of romantic-style melody we will surely die of thirst here. But it always seems to be just below the surface which makes for a frustration. The vocal writing is exacting in its conversational quality and there are no conventional arias and duets. Although this was my first experience with Blacher I was struck by similarities to Aribert Reimann who turned out to be one of Blacher’s star pupils and another great musical son of the Berlin Oper. He also wrote a number of classical and Shakespearian themed ballets that remain in their repertory today.

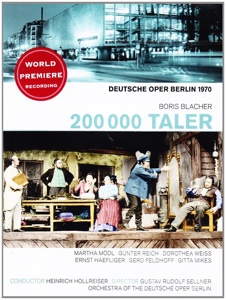

This video is derived from the world premiere production of 1970 directed by the Berlin Intendant Gustav Rudolf Sellner and conducted by Heinrich Hollreiser. The plot of the opera is derived from a short story by Sholom Aleichem (or as Blacher spells it ‘Scholom’) called Dos groijse gewins or “The Big Prize.” Aleichem’s “Tevye the Dairyman” was the basis of the musical Fiddler on the Roof in 1964, so you can’t help but wonder if Herr Sellner was hoping that particular bolt of Jewish lightning might strike twice.

Much is made, in fact, in the liner notes about the composer’s taking on a “Jewish” subject and he had already written the prologue to a joint composition ten years previous on the uprising in the Warsaw ghetto in 1943. The 1960s in Germany found a renewed interest in Jewish culture and tradition.

The story centers around the master tailor Schimele Soroker, his wife Golda, and their marriageable daughter, Bailke. Both of the assistant-tailors, Motel and Kopel, are hoping for Bailke’s hand. But then, so are Koltun the village caretaker and Solomon Fein, their landlord. In the first act Schimele tells everyone in the shop about a vivid dream he had where he finally wins the lottery. He then sends his young daughter out for his weekly ticket and she returns a short while later with the triumphant news that he has indeed won.Act II finds the family moved into their landlord’s best villa and up to their eyeballs in ongepatchke decor like you wouldn’t believe. They’ve even hired their neighbor, Perl, as their housekeeper. Now the contest for Bailke’s hand really heats up and she’s miserable at the thought of being married to one of the old men of the village, who are mostly interested in her dowry. Complications ensue until it’s discovered that Schimele’s ticket wasn’t the winner after all. In the brief epilogue, the family returns to their humble home and Bailke confesses her love to Motel, the assistant, and a (relatively) happy end results.

The name of Martha Mödl veritably lept out at me from the box cover and I was almost rabid to see this legendary Isolde, Brunnhilde and Kundry working her magic in the flesh. Her protean gifts are almost completely wasted playing a dutiful hausfrau and it came as a great disappointment. Her Golda is really nothing more than the devoted wife and I kept waiting in vain for her to do something über-dramatic like burn down the village or, at least, give someone a piece of her mind. Her vocal estate is what one would expect of this zwichenfach singer at the age of 58: still plenty of volume even if the days of ideal steadiness are past.

The Schimele of baritone Günther Reich is characterful enough and he was a celebrated Hans Sachs in Berlin, where he guested often, as well as specializing in the music of Schoenberg, Busoni and Berg. That must have been a benefit considering the score at hand. He’s especially evocative in the dream in the first act and it’s a big, warm voice that shows a keen use of intonation.

The young Dorothea Weiss brings a very bright and lovely sound to Bailke. She was later an acclaimed Butterfly throughout Germany before her early death at age 44. The voice has a clear top with a nice edge to it which would explain her preeminence in the Puccini.

The supporting cast is filled out by company members with the exception of the esteemed Swiss Tenor Ernst Haefliger as the assistant tailor Motel. Although a bit past his years for the young man he makes a touching suitor in the finale.

Sets and costumes by Ita Maximowna actually recall a bit of Boris Aronson’s work for Fiddler in the tailors shop of Act I. Once the family is gelted up, it’s all gathered draprs and tufted loveseats.

I’m going to take it on faith that Hollreiser knows what he’s doing with the baton because it was surely more counting and queuing than being swept away with anything. Nothing but pity for these aria-free characters in this modernist piece which should play like Falstaff with a plot like this but often sounds instead like the underscoring to a spy thriller where the hero is being interrogated. I understand that the basis of music is math I just don’t think it’s roots should be showing quite so much.

In spite of the written apology that comes up when you first load the disc the picture is quite good for 1970 but, then again, you know those German technicians. The major drawback to all of this is that it’s solely a television studio production and it’s lip-synched to a mono recording that literally sounds like it was done around a single microphone.

There’s absolutely no distance or sense of placement on any of the voices and the sound itself is flat as a board. Filming from the stage was still in its infancy and I understand why the choice was made but it nearly scuppers the entire project and makes a score already difficult to comprehend a pain in the ear. The lip-synching is especially glaring in spots and I can’t help wondering if a live performance would have been preferable.

So, a mixed bag. A rare work and a rare opportunity to see some great singers in the vicinity of their prime. Ultimately it depends on whether you’re a fan of the composer as to how much you’ll enjoy this performance.