“Here we again see the Berlin tendency towards hybrids; the great plans but tiny realization; great demands but tiny results; perfect reviewers but miserable musicians,” Felix Mendelssohn groused to a friend in the summer of 1841 after King Friedrich Wilhelm IV invited him to become general music director in the Prussian capital and focus on writing on grand oratorios and church music.

Rebellious in spirit but smart enough not to offend a monarch, the composer went on to spend an unhappy but brief tenure tangling with court bureaucrats and a cool public that more or less validated his early skepticism. One consolation was the chance to indulge his predilection for the past and produce incidental music for classical Greek plays such as Sophocles’ Antigone and Oedipus in Kolonos, which were then coming back into vogue in German-speaking countries.

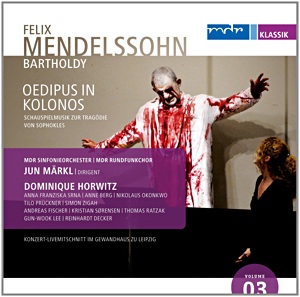

His 75-minute setting of Oedipus in Kolonos, heard in a live 2009 performance on MDR Klassik, illustrates how Mendelssohn tried to link ancient forms with Romantic-era sensibilities by fashioning harmonically adventurous chorales and believable characters instead of abstract musical representations of mythical figures. The music has a sacred yet gossamer quality that one early listener characterized as coming from distant, unknown times. Recitatives and melodramatic passages wrap around spoken text, and the self-contained choral numbers range from brooding laments on old age to exuberant richly melodic celebrations of life.

The story comprises the middle installment of Sophocles’ three Theban plays and depicts the final chapters of the blinded, exiled king’s life, decades after he unwittingly killed his father and married his mother. A prophet forecasts glories to the city in which Oedipus will be buried, prompting an attempt to abduct the monarch and bring him from Athens to Thebes. Oedipus defiantly resists and promises the Athenians a great blessing if he is allowed to stay and die in their city. In recognition of his past suffering and dignity, the gods grant him a honorable exit into the underworld.

Berlin audiences were reportedly unenthused by the musical treatment, perhaps finding it difficult to relate to a story so driven by visions and arcane religious beliefs. The cumulative effect of this performance may be similarly elusive to non-German speakers due to the frequent declamations, some 4 to 5 minutes long, and the absence of any libretto or translation. Most of the nine musical pieces are still first rate, filled with soaring melodies, gently pulsating accompaniments and sometimes daring dynamic shifts.

The lyrical and passionate “Zur rossprangenden Flur” is a showpiece that should be rescued from obscurity, while “Wer ein längeres Lebensteil” is a compact dramatic essay on Oedipus’ frailty that begins with soft singing to a gentle harp accompaniment and steadily builds to harness the full expressive and textural possibilities of the double men’s chorus.

Jun Märkl leads the MDR Radio Choir and Symphony Orchestra in a deftly shaped performance that’s completely at ease with Mendelssohn’s varied compositional techniques. A quartet of solo voices spins a dark, unsettled narration over delicate orchestration at the beginning of the penultimate choral song, just moments after the combined forces ring out in eight-part splendor in the almost Wagnerian “Auf uns bricht von dem blinden Greis.”

The orchestra is wonderfully transparent but warm in tone, with especially strong contributions from the woodwinds. The recorded sound from Leipzig’s Gewandhaus is spacious and balanced, even though the actors, led by Dominique Horwitz as Oedipus, are a bit too closely miked.

Though it will never match the incidental music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream in popularity, Oedipus in Kolonos has a lot to recommend for choral aficionados and presents an intriguing memento from an overlooked period in Mendelssohn’s life. Absent a background in the classics or affinity for the spoken word, more casual listeners may conclude it goes down easier with a skip button to bypass some of the dialogue.