“I’ve lived with mendacity!—Why can’t you live with it? Hell, you got to live with it, there’s nothing else to live with except mendacity, is there?” Big Daddy explodes with this cynical world view during Act 2 of Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and that speech crossed my mind as I pondered the two recent releases of “Vivaldi” operas on my desk.

The “inverted commas” stem from the knowledge that both CDs include scads of music that either cannot be definitively ascribed to Il Prete Rosso or that is explicitly attributed to other composers, yet only his name is sprayed all over the packaging and publicity.

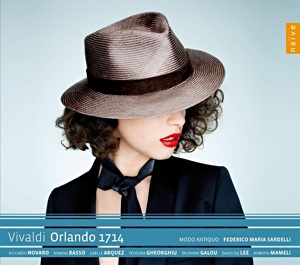

For some, Vivaldi embodies unchallenging “elevator” music of unimaginable repetitiousness—the same concerto rewritten 600 times, as 20th century composer Luigi Dallapiccola jabbed. Fortunately over the past several decades a sea change has transformed how Vivaldi is performed–and perceived, and the public’s hunger for his rhythmically infectious music continues. The explosion of interest in his operatic music has been a signal movement in the past decade, much of it attributable to the French label Naïve’s The Vivaldi Edition which now embraces thirteen complete operas with the release of Orlando 1714.

Since roughly half of the operas Vivaldi composed have not survived, there’s an almost desperate hunger to uncover something “new.” However, a storm of controversy has arisen over this peculiar work which lay unperformed in a library until it was resurrected at the 2012 Beaune Festival and recorded soon after. Ballyhooed as “a bombshell in the world of Baroque opera,” it proves to be far less explosive: an appealing, if truncated work which may not be entirely by Vivaldi.

Venice’s Teatro San Angelo was run by Antonio Vivaldi and his father Giovanni Battista when in 1713 Orlando Furioso by Giovanni Alberto Ristori premiered and became an enormous hit. Perhaps during its run of more than 40 performances the younger Vivaldi tinkered with it—adding some arias of his own– to keep it fresh. The following November Vivaldi’s own opera based on the iconic characters of Ludovico Ariosto’s epic appeared: Orlando Finto Pazzo was followed the next month by yet another Orlando whose pedigree remains mysterious, yet conductor Federico Maria Sardelli and musicologist Fréderic Delaméa hypothesize that it is that incarnation which is this new Orlando 1714.

The arguments about this version are far too complex to rehearse here, but I suspect that the torso (only the first two of the three acts have survived) we have is mostly likely not entirely by Vivaldi—why would he present a second work of his own based on the same characters just three weeks after the premiere of Orlando Finto Pazzo? It seems more likely that this reclamation presents a mélange of Vivaldi and Ristori. Little of that Bolognese composer’s work has been recently performed or recorded yet a live 2007 recording by Les Muffati of I Lamenti di Orfeo, a one-hour componimento drammatico by Ristori (admittedly a much later work than the lost 1713 Orlando), reveals a sensibility not incompatible with Vivaldi’s.

So, if not the revelation promised by its proponents, Orlando 1714 proves a pleasant two hours, the score’s holes filled with music from Vivaldi’s previous two works, Ottone in Villa (his first opera) and Orlando Finto Pazzo. Most of the arias are short, rarely over three minutes, and lack the complexity and pathos of his later works. However, Sardelli, his cracker-jack orchestra Modo Antiquo, and a stylish cast make a persuasive case nonetheless.Veteran Romina Basso’s commanding Alcina dominates the work. She has appeared in so many Vivaldi recordings that I’ve grown fond of her extravagant mannerisms as they arise from her earnest intensity rather than from self-indulgence. The remaining six members of the cast represent a younger generation of specialists in this repertoire.Unlike the later Orlando Furioso, Vivaldi’s most performed opera, this title role is for baritone (or bass), and Riccardo Novaro’s lean, focused voice deals handily with his increasingly unhinged music. His wrenching accompanied recitative which ends act 2 brings the recording to an abrupt but poignant end. Korean countertenor David DQ Lee’s sweetly sincere manner suits Ruggiero, and his lovely “Piangerò, sin che l’onda del pianto” with its plangent cello obbligato is one of the CD’s highlights.

The three sopranos, Teodora Gheorghiu, Gaëlle Arquez, and Roberta Mameli as Angelica, Bradamante and Astolfo, sadly all sound similar. One must frequently consult the libretto to determine who is singing. However, a charming Gheorghiu (Glyndebourne’s new Zerbinetta this spring and no relation to another Romanian soprano) evinces more personality than in her promising if ultimately disappointing debut recital Arias for Anna De Amicis.

Arquez has shone impressively in several French baroque operas and may prove better suited to them than to Italian ones. As demonstrated in Naïve’s Teuzzone, Mameli’s impressive coloratura remains winning, while the voice seems to be warming up—it had previously struck me as blandly chilly.

For those who treasure the previous twelve operas, Orlando 1714 will arrive as a lucky 13 for their Vivaldi Edition collection; however, others may find this pleasant performance insufficiently compelling, failing to equal the best of Vivaldi (or of Ristori, for that matter).

L’Oracolo in Messenia from Virgin Classics presents another complicated, yet eminently more satisfying example of ersatz-Vivaldi.

His first version of the opera premiered in Venice in 1737, but as his career in Italy foundered, he soon moved to Vienna in hope of reviving it but died there in 1741 without winning over its public. However, a posthumous L’Oracolo was preformed there during the year following his death, but, since neither score survived, conductor Fabio Biondi has reconstructed the work for this recording made during a performance in January 2012 at the Vienna Konzerthaus (sweetened by inevitable make-up sessions).

Biondi and Delaméa (apparently he’s involved in all things Vivaldi) in the CD’s notes conjecture that both L’Oracolos were pasticcios created by Vivaldi to exploit the success of an earlier work on the same subject, Geminiano Giacomelli‘s La Merope which premiered in 1734 at Venice’s Teatro S. Giovanni Grisotomo. Vivaldi had already poached two of its best known arias, “Barbaro traditor” and “Sposa, non mi conosci?” for his 1735 pasticcio Bajazet, also beautifully recordedLa Merope and L’Oracolo depict the internecine struggles for the throne of Messenia. Polifonte has had King Cresfonte and two of his sons murdered in order to become ruler. A third son Epitide escaped but eventually returns to Messenia disguised as Cleon to observe his mother Merope being pursued by Polifonte who seeks to marry her to further legitimize his position. The usurper has also kidnapped Elmira, Princess of Etolia who is married to Epitide. Inevitably, complicated intrigues ensue including Merope’s nearly murdering “Cleon” mistakenly believing him responsible for her son’s death. Eventually Cleon’s true identity is revealed and he is reunited with his wife and mother, reclaiming the throne from the vanquished Polifonte.

Using the surviving libretto, Biondi has recreated the 1742 version combining substantial music from Giacomelli’s opera (including most of the recitatives) with arias from six Vivaldi works. Giacomelli’s compelling music is different enough from Vivaldi’s that listeners may be disturbed by the shifts from one composer to the other. While attending the world premiere of this reconstruction in Krakow in December 2011, I remember being struck by the smashing act 3 aria for Licisco, one of the good guys. I was not surprised that it turned out to be from Johann Adolph Hasse’s Siroe since it sounded nothing like either Vivaldi or Giacomelli.

The biggest question I took away from that evening was “Why not just perform La Merope?”Franziska Gottwald, Biondi’s fiery Licisco, is one of six fine altos in the cast—Julia Lezhneva claims to be a soprano but I remain unconvinced. Basso returns as Elmira and again proves a striking interpreter, while in one of her best recordings Vivica Genaux as the disguised Epitide sings with her usual vibrant bravura, yet her tone remains too “curdled” to my taste. The beleaguered queen’s dramatic music is almost entirely Giacomelli’s, and Ann Hallenberg’s splendidly flamboyant incarnation, by turns incensed and anguished, is the biggest argument for the unadulterated La Merope. Yet what concert hall or recording company these days would schedule a work by Giacomelli when there was an alternative by “Vivaldi”?

While tenor Magnus Staveland’s Polifonte is an improvement on the ragged performance I heard in Poland, it remains frequently unfocused, far from suave villain required, particularly in “Nel mar così funesta” from Vivaldi’s Farnace which Daniel Behle so brilliantly tossed off in the recent complete recording.

Cresfonte’s assassin Anassandro plays a surprisingly minor role, but Xavier Sabata briefly steps into the spotlight to conclude the second act with a scintillating “Sento già che invendicata” from Vivaldi’s Catone in Utica, the work scheduled as the next opera installment in the Naïve series. The confounding Lezhneva also pops up from out of nowhere in the middle of the second act to deliver an inevitably dazzling “Son qual nave,” written by Riccardo Broschi for his brother, the great castrato Farinelli. After the Krakow premiere another aria from Catone was added for her presumably to capitalize on Lezhneva’s increasing fame. Clearly EMI believes she’s the star of this recording, but while both arias exhibit her usual jaw-dropping agility they also expose her inability to bring a distinctive personality to either the text or music.

Its origins as a live performance no doubt contribute to its dramatic power, but I suspect this L’Oracolo’s electricity springs from the inspiring leadership of Biondi and his thrilling ensemble Europa Galante. While other conductors do interesting work with Vivaldi et. al., Biondi brings such an intoxicating flair and dramatic imagination to his music-making that L’Oracolo proves, despite its fraught genesis, to be his most appealing opera recording to date, although Ercole sul’Termodonte merits attention as well.

Biondi’s recordings also provide a fascinating opportunity to play the old “countertenors versus mezzo-sopranos” game: Giacomelli’s “Barbaro traditor” turns up in both Bajazet and L’Oracolo. In the former, it’s sung by David Danielsand in the latter by Hallenberg.Max Emauel Cencic’s delightful Venezia: Opera Arias of the Serenissima finds today’s leading countertenor (I find him more impressive than the more famous Philippe Jaroussky) at the height of his considerable powers. This new Virgin CD features five arias indisputably by Vivaldi, along with rarer gems by Antonio Caldara, Francesco Gasparini, Tomaso Albinoni, Giuseppe Selitto, and Giovanni Porta, along with the inescapable Giacomelli “Sposa, non mi conosci,” which also surfaced

in Joyce DiDonato’s Drama Queens.

Like Sabata’s recent Bad Guys, Cencic is superbly accompanied by violinist-conductor Riccardo Minasi and his accomplished new band Il Pomo d’Oro.

If L’Oracolo in Messenia isn’t a clunky enough title, Venezia includes a selection from La constanza combattuta in amore by Porta whose work is also featured on Drama Queens. But my favorite track arrives from one of the many settings of Metastasio’s Adriano in Siria, Caldara’s exciting “Barbaro non comprendo.”

This composer clearly brings out the best in Cencic, as his Caldara cantatas CDWhile the forces involved with Orlando 1714 and L’Oracolo in Messenia might be found guilty of third-degree mendacity, curious listeners will accept this practical necessity and thereby be rewarded, particularly by Biondi’s infectious fervor. For the more principled, Venezia supplies a delicious–if non-mendacious–sampler, but all three releases offer up just some of many the glories inspired by La Serenissima.