On first hearing, Paul Dukas’ 1907 opera Ariane et Barbe-bleue (Ariane and Bluebeard) sounds like the love child of a three-way between Wagner, Strauss, and Debussy. But on further review, the music reveals some fascinating harmonic ideas that are unique to Dukas and provide a rich and intense landscape for this retelling of a centuries-old folk tale turned into a poetic and symbolist drama.

Belgian playwright and poet Maurice Maeterlinck originated the idea for this opera following his writing of the libretto for Pelleas et Melisande. He adapted the story of Ariane from Perrault’s popular Tales of Mother Goose, and wrote it specifically as a libretto. He first offered the libretto to Edvard Grieg, who demurred; Maeterlinck then turned to Dukas.

The opera Ariane et Barbe-bleue continues the interest of the turn-of-the century writers and composers in strong female protagonists; indeed the opera is dominated by female voices, with only choruses and a few lines of the startlingly absent Duke Bluebeard providing male voices. The role of Ariane is a huge and daunting one, in fact she never leaves the stage in the entire opera. It also requires enormous stamina to penetrate the heavy orchestration.

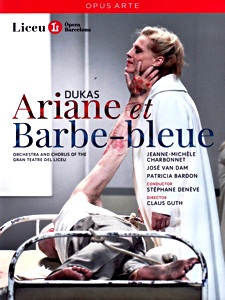

Director Claus Guth’s 2011 production of Ariane from the Liceu of Barcelona has recently been released on DVD from Opus Arte. It is an interesting visual production, with Ariane and the five wives all in various shades of white and cream on a set of gray walls and the mysterious doors (all but one of which can be opened by Ariane. ) When she violates Bluebeard’s orders and opens the door with the forbidden golden key, the floor opens to reveal a dark subterranean dungeon where the five previous wives are kept. Guth also employs projections on the walls for the outside of Bluebeard’s castle (here appearing as a country chateau) and the accompanying woodlands.

But, alas, the visuals do not a coherent production make. Throughout the piece, and particularly in the second act , the performers are just not doing what the libretto says they are doing. The act two business involving Ariane feeling about for the other wives in the dark dungeon doesn’t happen; Ariane merely sings the lines straight out and has no physical contact with the other women.

The end of the act, where the wives escape to the outside world, is risible—there is only the wives miming a boat, while the libretto describes an elaborate sequence of rock climbing and glass-breaking. Now, I do not ask that a production depict this realistically, which would likely be impossible. But I do insist on some fealty to the libretto, and at least an attempt at creating (perhaps with light and sound) the scenario described in the libretto.

In addition, Guth’s direction of the five wives is clichéd in the extreme. They all perform stock “I’m crazy” gestures (hair pulling, twitching, etc.) and are never allowed to form unique characterizations. Only Gemma Coma-Alabert as Selysette, the largest of the roles of the wives, manages to establish a distinct personality; the other four are sadly generic. Coma-Alabert also sings her role with a grace notably absent from the other performances.

The most serious problem in the production is soprano Jeanne-Michelle Charbonnet as Ariane. While her dramatic commitment is admirable, her fraying vocal estate is simply not up to the demands of the role. First of all, she sings everything at mezzo forte or above; her top notes are curdled screams with a wide vibrato. I find her basic timbre to be thick and rather unpleasant, particularly in the high tessitura of Act Two when she becomes downright unlistenable.

Patricia Bardon does some fine singing as Ariane’s Nurse, but she, too, becomes pressured and squally on top. The venerable Jose van Dam brings authority and presence to the very brief but mysterious role of Barbe-bleue.

Conductor Stephan Deneve leads a confident and expressive reading of the score but seems to be allowing the Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu to play at too high a volume throughout, forcing the already taxed singers into effortful attempts to be heard.

For me, this opera makes some very interesting points about feminist issues, particularly about the joys and terrors of freedom as a state that requires real struggle and confidence. The previous five wives are classical examples of “Stockholm Syndrome”, finally deciding to stay with the known entity, Barbe-bleue, rather than risking the outside world. Dukas may well have been reflecting Europe’s nervousness about entering the 20th century here, but Guth’s production does not illuminate the heady ideas of the libretto.

Comments