The chicken or the egg? Has the explosion of interest in the operas of Antonio Vivaldi mandated Naïve’s ambitious series of recordings

or did all those CDs create a hunger for more and more live performances?

About ten years ago while most of the recording industry was cutting back, the French CD company Naïve embarked on an extraordinary Vivaldi project which thus far numbers over forty volumes, twelve of them complete operas, including a reissue of Farnace by Catalan gambist/conductor Jordi Savall who also leads its latest opera release

, Teuzzone.

But the vogue for the Red Priest’s vocal works extends well beyond this influential Naïve project (which now includes Orlando Furioso on DVD) to a stunning new Farnace from Virgin Classics

, as well as superb aria collections by Ann Hallenberg

and Roberta Invernizzi

.

Today it’s difficult to believe that Vivaldi’s music virtually disappeared after his death in 1741 and remained mostly unplayed, uncatalogued and unpublished for over 150 years until scholars began to scour libraries and archives. If he was remembered at all before then, it was as a wildly talented violin virtuoso who was also a priest (but one who never said mass during the last 25 years of his life) and who had had a musical (and perhaps romantic) liaison with the celebrated contralto Anna Girò for whom he wrote several important roles.

His notoriety as a composer rested upon his connection to J.S. Bach who adapted—mostly for harpsichord–many Vivaldi concerti, with writers nearly always praising Bach for transforming the works of the lowly forgotten Italian. Not until a pioneering history of the concerto was published in the early 20th century did Vivaldi finally begin to gain his proper recognition and acknowledgment of how much in fact Bach had learned from his Venetian predecessor.

Unfortunately many Vivaldi scores had been scattered throughout Europe or lost entirely. The chaotic fate of those scores was particularly devastating to his operas; of 45 works he composed for the stage, fewer than half have survived, and some of those are incomplete. So far, no one has yet turned up such lost operas as the arrestingly titled Tieteberga, Scanderbeg, Cunegonda or Alvilda, Regina de’ Goti.

Thankfully the nearly 20 operas we have in more or less complete form amply illustrate Vivaldi’s striking gifts as a composer for the voice, in particular the alto voice (perhaps the influence of Girò?): The three complete operas reviewed below clearly demonstrate that voice preference:

- Teuzzone: two sopranos, four altos, one baritone (and one tenor who sings no arias)

- Farnace (Ferrara version): one soprano, four altos, two tenors

- Orlando Furioso: one soprano, five altos, one bass

Vivaldi’s vocal writing is sometimes criticized for being too “instrumental”—treating the voice as he would his violin. There is, of course, some truth to this charge—words often don’t seem to mean a great deal and indeed they often nearly disappear as voice races dramatically up and down the scale.

His more extravagantly showy arias are particularly noteworthy for the exciting intervals (common in his violin writing too) demanded of the singer, as in this aria from Griselda (done here in its original soprano version rather the truncated, transposed mess that was dropped into the Met’s recent The Enchanted Island):

While his operas seldom reveal the depth of characterization one finds in the best works of Handel, they do amply display some of the qualities that have made Vivaldi’s instrumental works so widely popular: a wild rhythmic intensity and propulsive drive, alternating with ravishing, transporting moments when time stands still.

Although there was a production of L’Olimpiade in Siena in 1939 (probably the first of any Vivaldi work since the composer’s death), the 1978 tricentenary of his birth proved a turning-point for the fortunes of his operas. In New York at Alice Tully Hall, Newell Jenkins’s invaluable Clarion Concerts presented a concert version of Farnace, the first Vivaldi opera performed in the US, while Italian Radio produced Griselda and French Radio La Fida Ninfa, and the Pier Luigi Pizzi production of Orlando Furioso starring Marilyn Horne (following her Erato recording of the opera) premiered in Verona.

In 1980 Horne and Pizzi brought that Orlando (in its badly cut and rearranged edition) to Dallas, the first US staging of a Vivaldi opera. Sadly by the time the Pizzi production was videotaped in San Francisco Horne was past her prime, but I’ll never forget in the late 70s listening to her thrilling rendition of Orlando’s grand Nel profondo; it was probably the first Vivaldi aria I’d ever heard and utterly unlike anything in Handel or other high baroque composers that I knew at the time:

As the first recording vogue for Vivaldi’s concerti flourished in the 60s and 70s with groups like I Solisti Veneti (which accompanies Horne on the Erato Orlando) and I Musici, many of today’s best Vivaldi performances also come from Italian-based groups like Europa Galante, Accademia Bizantina, Il Giardino Armonico, Venice Baroque Orchestra, and Rinaldo Alessandrini’s Concerto Italiano, whose 2002 L’Olimpiade launched the Naïve Vivaldi opera series whose latest release is 1719’s Teuzzone.

For no apparent reason, librettist Apostelo Zeno sets the work in China prompting the CD booklet’s provocative essay to misleadingly label the work “Vivaldi’s Turandot.” However the libretto by Zeno (Metastasio’s predecessor in Vienna) proves a fascinating work of political intrigue with a remarkable opening: the King of China dies on stage during the opera’s first scene (a scene nearly unprecedented in opera seria of the time).

Immediately his scheming betrothed Zidiana begins to maneuver to succeed him in her own right, in addition to marrying his son Teuzzone whom she secretly loves. He of course loves another: Zelinda–it’s fascinating to contemplate the semiotics of Zeno’s naming the women in Teuzzone’s life Zidiana and Zelinda!

Despite earning a recent rave review in The New York Times, Savall’s recording strikes me as one of the weakest of Naïve’s dozen. Savall has conducted only a handful of operas during his long and prolific career, and I remain unconvinced he is suited to opera. An improvement over his earlier Farnace, Teuzzone lacks drama.

Although Naïve is a bit coy on the topic, apparently the recording was made during two live concert performances at Versailles in 2011, yet it could easily have been done in a studio since there’s little feel for the high-stakes drama, and the recitatives are particularly bland. Arias are livelier, but these torn characters rarely spring to life. Savall’s Le Concert des Nations, however, is more vivid here than in Farnace, perhaps due to its concertmaster, the brilliant Italian violinist Riccardo Minasi who is also featured on Naïve’s latest volume of violin concerti. (Minasi is, incidentally, married to American mezzo-soprano Kate Aldrich.)

However, Savall’s Teuzzone suffers most from casting missteps, especially male soprano Paolo Lopez in the title role, an odd choice since the role was atypically written for a female soprano Margherita Gualandi, known for her exciting temperament. Lopez sings well enough, but it’s a small, carefully negotiated sound that fails to do justice to Teuzzone’s dangerous predicament.

As his nemesis Zidiana, Raffaela Milanesi sounds ill at ease in what is clearly a mezzo role where she must force her silvery soprano lower than her usual comfort zone. Antonio Giovannini, due to open Carnegie Hall’s season in October in Orff’s Carmina Burana with Riccardo Muti and the Chicago Sympbony Orchestra, unleashes a hooty countertenor and makes little of Egaro’s admittedly lackluster arias. A veteran of many baroque recordings, baritone Furio Zanasi sings pleasantly but without the vigor that could grab attention for Sevenio.

The recording is dominated by two relative newcomers. Cino is not an important figure in the drama, but the castrato who first sang the role was the highest paid singer in the cast ensuring that he got the showiest arias which soprano Roberta Mameli handles excitingly.

As Teuzzone’s long-suffering lover Zelinda, French contralto Delphine Galou vividly demonstrates why she has quickly become today’s “go-to” girl for so many conductors of 18th century opera. Her dusky yet agile voice assures that her anguished arias become the emotional highpoints of Teuzzone. One hopes the promising Galou will proceed wisely avoiding the pitfalls that seem to have compromised her contralto peers, Marijana Mijanovic and Sonia Prina.

I’ve never much liked Savall’s Farnace originally recorded for Alia Vox and reissued on Naïve. One of Vivaldi’s own favorite operas, Farnace exists in several versions, none complete. Savall recorded the 1727 version with a bass Farnace and a mezzo Pompeo. However, the new Virgin Classics release conducted by Diego Fasolis features the 1738 Ferrara version where Farnace becomes a countertenor and Pompeo a tenor.

Both recordings fill in music missing from their editions; Savall adds arias from Francesco Corselli’s 1736 Farnace. As the Ferrara edition entirely lacks its entire third act, Fasolis and Frédéric Delaméa (an inevitable collaborator today on all matters Vivaldi) have concocted the missing act, seamlessly matching the existing acts in ways that the Savall-Corselli additions don’t.

Like Teuzzone, Farnace features a compelling libretto by Antonio Maria Lucchini, but here Vivaldi is inspired to heights unreached in that earlier opera. The defeated king Farnace commands his wife Tamiri to kill both herself and their son to avoid being captured by the enemy.

Meanwhile his monstrous mother-in-law Berenice conspires with Pompeo, leader of the victorious Romans, to kill him. However, Farnace’s sister Selinda uses her wiles to bewitch two of their captors, Aquilio and Gilade. Her machinations succeed and all are saved, after a spectacularly unconvincing change of heart by Berenice.

Virgin’s Farnace may be the best conducted, most strongly cast Vivaldi opera yet recorded: Diego Fasolis’s I Barocchisti crackles with energy, playing superbly and never crashing into the fussy mannerisms that Jean-Christophe Spinosi and his Ensemble Matheus indulge in on several other Naïve operas, and the recitatives are compellingly performed.

In the title role Max Emanuel Cencic grandly throws down the gauntlet to his fellow Virgin recording artist Philippe Jaroussky to stake his claim as perhaps today’s leading countertenor. Cencic summons up a splendid intensity to dominate the performance, singing with flair while carefully limning a man torn between allegiances to his duty and to his family.

As Cencic might be construed to be the recording’s raison d’être, two additional arias are appended to the end of the third CD for him, including the opera’s most famous aria (from the original 1727 version and written for a bass but transposed up here for Cencic):

As his tormented wife Tamiri, mezzo Ruxandra Dunose sings fervently despite some unfocussed high notes. Although relatively inexperienced in early 18th opera, Dunose acquits herself well, although she lacks the idiomatic intensity which made Sara Mingardo’s Tamiri so moving in a recent broadcast with Cencic from Amsterdam also conducted by Fasolis. Fiery mezzo Mary Ellen Nesi is a predictably vivid Berenice although she’s unable to make her character’s last-minute turnabout very convincing.

While tenors can often let down the home team in Vivaldi, both Emiliano Gonzalez-Toro as Aquilio and Daniel Behle as Pompeo are very impressive, particularly Behle in his bravura “Non trema senza stella” which concludes act I.

While one might have ordinarily expected mezzo Ann Hallenberg and soprano Karina Gauvin to have traded roles, Hallenberg’s roguishly sexy Selinda proves surprisingly bewitching, while Gauvin pines winningly as Gilade, threatening to steal the show with her stylish “Nel’ir timmo del petto” with its wonderfully keening horns.

Several of Virgin’s cast appeared this past spring at the Opéra National du Rhin in a staging of Farnace by American choreographer Lucinda Childs which was subsequently webstreamed and remains available for viewing online.

It’s an effective production (Childs did particular wonders with Cencic who has rarely been so commanding on stage)–a further argument for the stageworthiness of Vivaldi’s operas, yet it’s not as strong musically as Virgin’s recording. Pompeo and Selinda are notably weaker than Behle and Hallenberg, and, despite her sterling credentials as a baroque singer, Vivica Genaux lacks the shine and allure of Gauvin’s Gilade. Conductor George Petrou and the wonderful Concerto Köln do well without equaling Fasolis and I Barocchisti.

The Naïve DVD release of Orlando Furioso –by far Vivaldi’s most often-performed work for the theater–reunites the conductor, orchestra and four of the principals of its 2004 CD in a production by Pierre Audi mounted at Paris’s Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris in March 2011.

Using characters from Ariosto’s epic poem, Grazio Braccioli’s libretto swirls together in one opera what it later took Handel two operas to manage. Alcina, Ruggiero and Bradamante from Handel’s Alcina are brought together with Orlando’s Angelica, Medoro and Orlando.

Vivaldi’s 1727 piece instead intertwines these two fraught love triangles, although their connections to each other can occasionally seem a bit tenuous. The mad Orlando was clearly a character who fascinated Vivaldi as he wrote an entirely different opera about him earlier in his career, 1714’s Orlando Finto Pazzo (also to a libretto by Braccioli), with Bradamante the only other character appearing in both.

Audi’s production–with busy monochromatic sets and costumes in black and gray by Patrick Kinmouth and lighting by Peter Van Praet–takes an intense, darkly psychological look at Ariosto’s characters. Audi is sometimes criticized as not being regie enough for many tastes in Europe; true, there are none of the usual tropes of regietheater here—characters do not wear contemporary clothing (but rather 18th century dress), no one smokes nor wears glasses, no guns are brandished nor blood spilled nor does any simulated sex occur onstage.

However, Audi does subscribe to the modern affectation for having any many characters onstage as he can—more often than not, all seven singers are there watching, waiting, reacting even when they’re not intended to be. But it manages to create a highly charged environment where we witness the profound consequences felt by everyone during each character’s arias.

Adorned with considerable, unfortunate facial hair, contralto Marie-Nicole Lemieux as Orlando resembles someone one might run into during a Provincetown “Bear Weekend.” Though usually a fine Vivaldi singer, unfortunately Lemieux alarmingly indulges in her tendency to go over the top so much so that a good deal of her singing becomes shouted and ugly. The audience seems to eat up this all-out dramatic commitment but for my taste the music suffers far too much in return.

As Alcina’s desperation grows, Jennifer Larmore increasingly falls prey to a similar overzealous dramatic intensity, pushing the sound threadbare and hoarse. Lemieux, Larmore and Veronica Cangemi (often pinched and wiry as Angelica) all suffer in comparison to their younger, better selves on the CD version.

Only Jaroussky’s Ruggiero need not fear comparison to his 2004 performance; although not much of an actor, he sings beautifully throughout, particularly his ravishing “Sol da te” accompanied by a traverse flute:

In smaller roles, Kristina Hammarström, Romina Basso and Christian Senn are excellent as Bradamante, Medoro and Astolfo but not markedly better than their CD counterparts. Jean-Christophe Spinosi may have read some of the stinging criticisms of his fussy conducting and tones down some (but not all) of the violent, jarring contrasts he’s so fond of. As music-drama, this Orlando is a remarkably vivid experience; however, for repeated listening, rather than viewing, one should turn to the CD.

Since scholars continue to unearth “new” Vivaldi pieces all the time, Naïve has added a New Discoveries series, the second volume, like the first featuring Federico Maria Sardelli conducting his wonderful Modo Antiquo, has just been released.

Four challenging arias from L’inganno trionfante in amore and one from Ipermestra are splendidly sung by mezzo Ann Hallenberg, but while worth hearing, none are particularly memorable, nor is the concerto for traverse flute done by Alexis Kossenko whose disconcertingly loud breathing distracts from his otherwise fluent playing.

However, the CD is highly recommendable for three spectacular violin concerti played by Anton Steck. Though (like Telemann) Vivaldi has been dissed for rewriting the same concerto several hundred times, his violin concerti always seem fresh and fascinating and the Steck-Sardelli collaborations here are particularly beguiling.

In addition to the complete operas, there has been a surprisingly large number of opera aria CDs released in the past few years, including one by Nathalie Stutzmann who not only sings but conducts her own orchestra. Others include Magdalena Kozená

, Vivica Genaux

, Philippe Jaroussky

, Simone Kermes

and Topi Lehtipuu

.

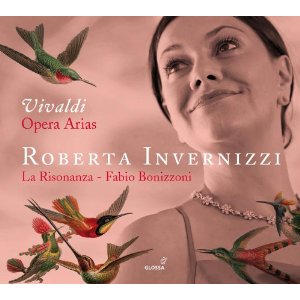

The most recent, however, is also one of the best so far: Italian soprano Roberta Invernizzi’s collection of 14 arias from nine operas has just been released on Glossa, a collaboration with harpsichordist/conductor Fabio Bonizzoni and his group La Risonanza who are also responsible for the recent revelatory seven-volume set of Handel’s instrumental cantatas also on Glossa, many of which feature Invernizzi.

This CD highlights her smoky, womanly voice which–one must admit–doesn’t negotiate the elaborate coloratura quite as effortlessly as it once did; however, she remains spellbinding in the slow arias, particularly Tu dormi in tante pene from Tito Manlio where her finely-spun long lines magically intertwine with Nicholas Robinson’s solo violin obbligato.

Recently Invernizzi has become more daring in her singing, sometimes dipping startlingly into chest voice—her dramatic commitment suggesting that these arias aren’t solely about vocal display. An unfortunate omission from the CD is Hippolita’s gorgeous Onde chiare chi susurrate from Ercole sul Termodonte, doubly unfortunate since Invernizzi sang the role often with Fabio Biondi but was bumped by Virgin from the complete recording for the more “commercial” Joyce DiDonato who of course sings well but without Invernizzi’s inimitable Vivaldi style:

And there’s yet another Orlando in the pipeline! Since the thirst for “new” Vivaldi works continues, the astonishing news that most of a hitherto unknown early version of Orlando Furioso had been found made headlines around the world, and France’s Beaune Festival hosted its modern premiere conducted by Sardelli on 20 July after which it was recorded by Naïve.

However this “new” Orlando is already proving controversial. Some commentators have argued that the unbridled hunger for Vivaldi rediscoveries has clouded good musicological judgment and that this score is actually Giovanni Ristori’s Orlando which Vivaldi merely had a hand in revising. We’ll have to wait for the CD’s release later this year to decide.

For those not yet bitten by the Vivaldi bug, the Invernizzi miscellany makes a splendid introduction. And, in addition to the Virgin Classics Farnace, I would recommend two of the more recent Naïve operas, Ottone in villa conducted by Giovanni Antonini and La fida ninfa

(a charming lighter opera with a cast headed by an inspired Sandrine Piau and led by Spinosi on—mostly–his best behavior).

Although it’s not at all “authentic,” one would be hard pressed to find a more enjoyable soupçon of the operatic Vivaldi than this crazy private video where Lemieux and Jaroussky duel in an encore of Orlando’s Nel profondo–worlds away from Horne’s ’70s version!

Reach your audience through parterre box!

parterre box, “the most essential blog in opera” (New York Times), is now booking display and sponsored content advertising for the 2023-2024 season. Join Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Warner Classics and many others in reaching your target audience through parterre box.

parterre box, “the most essential blog in opera” (New York Times), is now booking display and sponsored content advertising for the 2023-2024 season. Join Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Warner Classics and many others in reaching your target audience through parterre box.

Latest on Parterre

Merry Widow | Finger Lakes, NY | July 25-28

Geneva Light Opera’s production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow will feature prize-winning baritone Bryan Murray and soprano Alexis Olinyk in the superb acoustics of in the landmark Smith Opera House in Geneva, New York on July 25, 27, and 28. A small city on the north end of the largest of NY’s Finger Lakes, Geneva…

Geneva Light Opera’s production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow will feature prize-winning baritone Bryan Murray and soprano Alexis Olinyk in the superb acoustics of in the landmark Smith Opera House in Geneva, New York on July 25, 27, and 28. A small city on the north end of the largest of NY’s Finger Lakes, Geneva…

parterre in your box?

Get our free weekly newsletter delivered to your email.

Comments