Muhly’s opera, with libretto by Craig Lucas, is both a detective story and cyber-cautionary tale of “the dark side of the Internet”. It unfolds, rather baroquely as flashbacks within flashbacks. As the opera begins, a detective inspector is reflecting over the confusing facts of a difficult case. One teenage boy has been accused of stabbing another behind a shopping mall; the accused claims a masked stranger attacked them, but security camera footage suggests otherwise.

As explanation of how he came to be at the crime scene, he offers his story of how an encounter with a frightened teenage girl in a chatroom grew into something quite perilous. His online chats, sung as duets with text projected above and sometimes on the set, with an increasingly ominous set into a world of conspiracies, sexual predators, and genuine physical danger. Revealing more of the plot would subvert the intentions of the creators and the ENO who revealed as little of the plot as they could in interviews and promotional materials.

Even the program book forsook the typical plot summary. A “didhedoit” might seem a slim basis for a full-length opera, but the libretto supplies enough intrigue, passion, and violence to serve as gunpowder for an evening’s worth of operatic fireworks.

However, the treatment feels cinematic, not operatic, rushing headlong from scene to scene with the music gamely trying to keep pace, rather than drive the work forward or reflect on the action. It was only in the mesmerizing choral interludes, depicting the online world that the music gained the attention it deserved elsewhere. The net result was a dramatic choppiness that fought against any sense of broader musical structure in the work. Operas are written in paragraphs and this felt too much like a series of strung together sentences.

Now, many of those sentences were exquisitely beautiful; Muhly has a remarkable ear for sound, his mastery of timbre in his orchestral writing was heard to particular advantage in the interludes which depict the bustle, buzz, and back alleys of the online world without resorting to electronic sounds.

Other highlights included an all-too-brief church scene the sequence in which the detective solved the crime (including a lovely musical “a-ha”) and the opera’s final choral peroration His setting of text was also very admirable both for allowing the clear projection of words and for the well-judged deployment of melisma.

The performers presented the work with a palpable commitment and enthusiasm, even if the orchestra under conductor Rumon Gamba got occasionally tongue-tied coping with the musical language. As the inspector, Susan Bickley captured her character’s resolve and determination, despite a part that demanded that she spend much of the opera in a state of exasperated befuddlement.

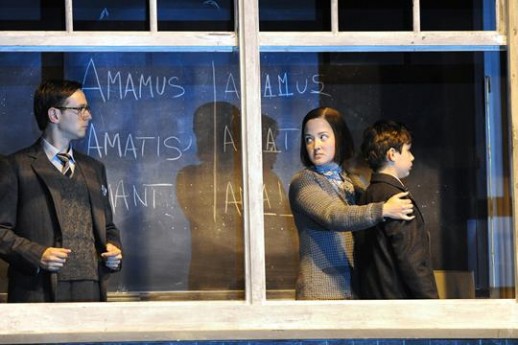

Other major roles were cast with young, relatively unknown singers, all of whom made their most of the opportunity. Tenor Nicky Spence as the accused Brian was particularly fearless, both in his emotional intensity and his willingness to take on some sticky, as it were, sexual business that other performers might balk at.

Soprano Mary Bevan, as Rebecca, Brian’s threatened chat partner, projected the right mix of allure, vulnerability, and ambiguity. Joseph Beesley as a boy soprano Brian hears sing in church had an extremely powerful voice of surprising emotional range. One hopes that most of these singers travel with the work to the Met, although one doubts Mr. Beesley will still be singing treble roles in two years.

Overall, it’s a work I would want to experience again, particularly in a different production. The ENO/ Metropolitan Opera co-production by director Bartlett Sher made significant use of video projections done by members of 59 Productions. Their videos were haunting, capturing both the seductiveness and threat of the online world, but they couldn’t salvage the overall production, which had some particularly maddening directorial choices.

One was that the set was in nearly constant motion; the detective’s desk did multiple laps around the stage before the evening ended. A character might be in the middle of a thought or there would be a particularly dramatic interchange and then the set would start shifting, seriously disrupting both the music and the drama.

Secondly, there was no consistency or logic to how the characters’ excursions to the online world were displayed. A character might start a chat on an empty stage only to have their desk with computer carried on by stagehands in the middle of the scene. Characters chatting electronically with Brian might be positioned at opposite ends of the stage and then suddenly enter his room, a powerful device if it were deployed with some consistency and didn’t cause confusion when characters appeared in Brian’s room who were actually in there.

In another extreme instance, Brian presented his recollection of a chat and then the staging showed what happened to the other participant in the chat after the chat ended, even though Brian couldn’t have seen the events and we were supposed to be watching his recollections. It was not a production, alas, to win over the doubting members of the Cher Public to the Sher Public.

Lack of a steady directorial hand was not an issue for Alden’s disturbing new production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream seen at its last performance of the run. It scored a regie hat-trick as it simultaneously managed to tell the story of the opera, to highlight the psychosexual content of the won and to reflect upon how the plot and themes of Dream might have had a particular resonance for the composer.

The setting is the deserted courtyard of a British boy’s boarding school late at night. Before the music begins, a young man, whom we eventually learn is Theseus, wanders on in a pensive mood. The program book tells us he is there on the eve of his wedding. He sits on the ground and drifts off, deep in thought, eventually falling asleep and starting to dream. His dream is the opera and it soon reveals why he might be drawn back to his school as he is about to begin married life.

The school is an oppressive place, the threat of violence, physical or sexual, seems very real. Puck is Theseus as a younger boy. Oberon is the domineering headmaster; Tytania the music teacher; and the fairies are the students at the school. Oberon and Tytania’s cruelly manipulate the boys by offering them the possibility of being their “favorite”. Puck has just lost his favorite status and he is desperate to be back in Oberon’s good graces, even though a new boy (“the boy stolen from the Indian king ”) is now the object of Oberon’s affections.

Puck must not only help Oberon get revenge on Tytania for toying with Oberon’s new chosen lad, but he must also, as the logic of dreams would have it, wreak havoc on the relationships of his current-day friends (the quartet of lovers) and other citizens who will provide entertainment at the wedding (the rude mechanicals). The havoc is quite extreme. In act II, the school is set afire and in a considerable display of stagecraft burns intensely, but is not consumed.

Just as the chaos is calming down at the end of Act II and the fairies sing their consoling lyric “The man shall have his mare again, And all shall be well” over ambiguous harmonies, an ominous veiled woman walks on to the horror of the dreaming Theseus; this turns out to be his bride to be Hippolyta. Eventually, Theseus awakens from his dream and goes off to be married and enjoy a bawdy play, but Puck’s return for his final exhortation to the audience, delivered here with anger and bitterness, reminds us that abused boys never quite believe that they have awakened from their nightmare.

This approach resonated with the music and the text in surprising and enlightening ways. It connected Dream in a to Britten’s other works about loss of innocence and corruption. Puck, the only child on stage whose voice has changed, has lots his innocence for good. The tension between angelic children’s voices and the erotic lyrics and yearning harmonies of the fairies music was even more unsettling than usual.

In other stagings, a counter-tenor Oberon can come across as rather camp, even if musically and sonically apt. Not so here. Oberon was intimidating and more than a little frightening. He caned Puck savagely for his misdeeds (and made the Indian boy hold him down) and casually flicked the still hot ashes from his cigarette onto the lovers to cast his spell.

Once again, ENO fielded a mostly young, impressive cast. However, it was the veteran Willard White who walked away with the show. He brought such eloquence and nuance to the role of Bottom; his interpretation found all the wonder at the possibility of transformation that Britten put in Bottom’s music

Notable , too were the Oberon, Iestyn Davies, who a countertenor of exceptional projection and impact and the Lysander, tenor Allan Clayton, who has a voice of considerable heft and intensity. Conductor Leo Hussain delivered a reading of the score that matched the tone of the production – menacing, barbaric, and dangerous.

The best opera productions get the audience to pay close attention to a work they think they know by highlighting details in the music and text that may have gone unnoticed Dream at the ENO had me riveted.

Photos: Alistair Muir (Midsummer), Richard Hubert Smith (Two Boys).