This Cleofide must have been conceived as a perfect target for haters of Italian baroque opera. While many might (grudgingly?) acknowledge that Handel is indeed an important operatic composer, here we have a virtually unknown name often relegated to dusty music history books. Not only has no one ever heard (nor probably even heard of) this opera, it contains neither tenor nor bass roles.

So, we’re treated to not one, not two, but three countertenors with a male soprano thrown in for good measure. And in the title role of the seemingly duplicitous Cleofide who must feign attraction for her lovesick conqueror in order to save her husband’s life: Emma Kirkby!

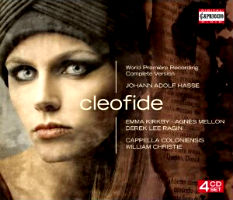

The conductor, best known for French rather than Italian baroque, leads not his own orchestra but a German one he’s never conducted before. And the nearly four hour work is done complete—a string of over twenty-five da capo arias—broken only by the single duet that ends act one. What could Capriccio and WDR (West German Radio) have been thinking when they dreamed up this project? Well, it turned out marvelously, and all but those (few?) haters will be pleased that on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the recording sessions (May 1986), Capriccio has re-released this set at a bargain price.

Foremost, we’re offered a rare opportunity to experience an important opera seria from Dresden, which for the late 17th and most of the 18th centuries was one of the musical capitals of Europe, a city where Zelenka, Pisendel, Heinichen, Caldara, Lotti, and many others worked. After years training in Italy with Porpora and Alessandro Scarlatti, Johann Adolf Hasse returned to his homeland in 1731 for the premiere of Cleofide, the first opera of many he wrote for the city where he would preside as its leading opera composer for over thirty years.

Cleofide is based on the libretto Alessandro nell’Indie by Pietro Metastasio, the most important librettist of his time and a great friend of Hasse’s. Set as many as seventy times by composers from Vinci to Cimarosa to even Pacini in the 19th century (his version was recorded by Opera Rara), its bewilderingly complicated plot follows a conquered king and queen, torn asunder, threatened with betrayal and death but all, of course, ends quite happily yet fairly unconvincingly. Rather, it’s much easier to simply experience the story as two love triangles—each of the two female characters pursued by a “right” man and a “wrong” man.

Named after Cleofide’s husband, Poro, Handel’s version of Alessandro (one of only two Metastasian libretti he set), is one of his best yet most neglected works. (Fabio Biondi’s superb recording of Poro, currently out-of-print, is well worth hunting down.) Does Hasse’s opera ever reach the musical and dramatic heights of Handel’s? No, but Hasse’s music is always wonderfully inventive and full of life, but it more often than not fails to achieve those depths of feeling that could really move a listener. Except for occasional moments of true pathos, most of the music doesn’t really seem to take its life-threatening situations nearly seriously enough. For example, the conqueror Alessandro whose designs on poor Cleofide turn the plot seems more like an obstreperous peacock than a real threat. Yet, it’s all very appealing and infectious—one can hear why Hasse was such an immensely popular composer in his time.

Hasse and Handel were connected in another interesting way: Faustina Bordoni, the celebrated soprano who created several important roles for Handel in London in the 1720s, married Hasse in 1730 and was the first Cleofide. She also became half of one of the most notorious scandals in diva history. Faustina was brought to London and immediately a ferocious rivalry developed between her and Handel’s reigning soprano, Francesca Cuzzoni. John Arbuthnot recounted a famous incident (probably apocryphal) involving the ladies:

“A most horrid and bloody BATTLE between Madam FAUSTINA and Madam CUZZONI… TWO of a Trade seldom or ever agree … But who would have thought the Infection should reach the Hay-market and inspire Two Singing Ladies to pull each other’s Coiffs, to the no small Disquiet of the Directors, who (God help them) have enough to do to keep Peace and Quietness between them…. I shall not determine who is the Aggressor, but take the surer Side, and wisely pronounce them both in Fault; for it is certainly an apparent Shame that two such well bred Ladies should call Bitch and Whore, should scold and fight like any Billingsgates.”

This catfight was later satirized by John Gay in The Beggar’s Opera in the scene between Polly Peachum and Lucy Lockit—it all sort of makes Anna Netrebko dissing another anonymous soprano in print look pretty benign.

As Bordoni’s voice was most likely what we today would consider a mezzo, Kirkby vocally handles the role quite capably—no demands on her squeaky upper register. As mellifluously as she sings (and, yes, she can trill), her bland demeanor creates somewhat of a vacuum at the opera’s center. Luckily the rivals for her love create much more dramatic characters. Derek Lee Ragin gives one of his most exceptional and flamboyant performances as Poro. Ever an intense singing-actor, he spurs Kirkby to her most committed singing in their sole duet. Although her phlegmatic manner is a major blot, it doesn’t ruin the performance and other than a similarly ill-advised recording of Dorinda in Handel’s Orlando, Kirkby henceforth avoided opera in Italian.

Many have noted that Dominique Visse has a most “characteristic” voice—well, probably more have called it “hideous/ugly”, etc. actually. Yet with it, he creates a vivid villain in Alessandro for whom Hasse has written some of the most colorful music, particularly his pompous final aria featuring a dialogue between a valveless horn and a theorbo. Visse also masterfully infuses the da capo repeats with musical and dramatic interest; in fact, consistently exciting ornamentation throughout adds considerably to this Cleofide. So often in opera seria performances one feels like the ornaments are either too much or not enough, but here they are “just right.” And Visse is still at it: prancing around as Natalie Dessay’s eunuch in Laurent Pelly’s production of Giulio Cesare in Paris earlier this year.

The opera’s second love triangle surrounds Agnes Mellon as Poro’s sister Erissena. Although fairly low-key, hers is a winsome, charming portrayal. Her “right man” is Gandarte, sung by male soprano Randall K. Wong. Once one gets used to his small, slightly frail, even girlish timbre, his singing often astonishes in the spectacular ornaments of his da capos.

Perhaps because the voice can sound awfully twee, Wong’s career in baroque opera really didn’t pan out other than a few concert appearances in the 80s. I was astonished to hear him during the 90s camping “Glitter and Be Gay” at St. Mark’s-in-the-Bowery during a performance piece created by Tom Bogdan, a fellow member of Meredith Monk’s troupe.

As Gandarte’s rival for Erissena, Timagene, David Cordier nearly makes up for a goodly number of really awful recordings, including Bertarido in Michael Schneider’s Rodelinda, one of the drippiest examples of countertenor singing on disc. But, here, he sings strongly and quite appealingly, a real surprise after so many other misfires.

Miraculously, this recording has been so carefully cast that each male singer projects a distinct vocal character so there’s never a problem identifying who is singing—not an easy thing with four falsettists involved. Along with his canny choice of singers and the dazzling ornamentation, Christie also conducts a wonderfully vibrant, colorful, and often thrillingly fast reading of the score. Instead of his own Les Arts Florissants orchestra, he leads the Capella Coloniensis, possibly the oldest “original instrument” group in existence. Many will be familiar with it from the famous 1958 broadcast of Handel’s Alcina with Joan Sutherland and Fritz Wunderlich (recently released on Deutsche Grammophon). Nearly forty members strong (a huge orchestra for a baroque opera recording), this German group is supplemented by two wonderful French harpsichordists, Yvon Reperent and Christophe Rousset, presumably brought along by Christie.

Surprisingly given the success of this recording, Hasse’s fortunes in the intervening twenty-five years haven’t really changed all that much. Although I’ve heard more than a half dozen broadcasts of concert performances of Hasse operas, very few have been staged. Some recordings have appeared since 1986, many of religious works, along with two versions of Piramo e Tisbe, a much shorter opera requiring only three singers.

More recently several baroque “stars” have recorded Hasse arias: Andreas Scholl, Philippe Jaroussky, Simone Kermes and particularly Vivica Genaux, who sang in two large Hasse works with Rene Jacobs. In fact, Genaux has been touring a Bordoni program (“I am Faustina!”) all over Europe this season. However, as Genaux’s singing usually sets my teeth on edge, I have not sought out her Hasse recordings. Very recommendable, however, is an Archiv CD of sacred music beautifully sung by Bernarda Fink and Barbara Bonney, as well as a harder-to-find CD on Virgin Classics of I Pellegrini al Sepolcro di Nostro Signore. But Cleofide remains the essential Hasse recording, particularly now at a bargain price!

Comments