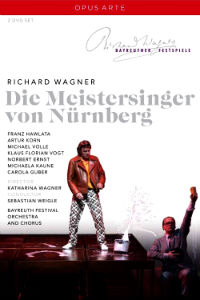

In the summer of 2007, at the height of the heated speculation and public debates over who would succeed Wolfgang Wagner as the head of the Bayreuth Festival, his daughter, Katharina Wagner presented a new production of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg at the festival, replacing the mind-numbingly boring one by her father (his third at Bayreuth).

It’s hard not to see this production as an audition for the job of General Manager; in fact, Katharina and her half sister Eva Wagner-Pasquier were named as co-managers of the festival the following year.

At the time, the 29-year-old director had only directed four other operas including an intermittently bewildering modern-dress Lohengrin in Budapest. There are extended excerpts of that production available on YouTube that are worth watching for the fire-breathing Ortud of Eva Marton.

This new DVD presents a performance from the second run of performances. Her production is unapologetic full-bore Regietheater, determined to compel the viewer to think about the work and the role it has come to play both at Bayreuth and in German culture.

Its central thesis is a powerful one: Die Meistersinger has come to be viewed in a way that is the reverse of what Wagner intended. His tale of the outside innovator who triumphs over cultural conservatives to invigorate a stagnating art has ironically been appropriated by cultural and political conservatives who use the work to defend both traditionalism and purity in art.

To convey this paradox, she turns the work on its head. Nuremberg is a suffocating, militaristic arts academy where the automaton-like students are taught only to reproduce the works of the past. David’s apprenticeship consists of xeroxing pages from the bottomless supply of yellow Reclam paperback editions of standard classics. Sachs is the token iconoclast; he doesn’t wear a tie, smokes, slouches, and walks around barefoot like any reputable cobbler. Walther is a performance artist, graffiti painter and all-purpose bad boy who crashes into Nuremberg when he climbs out of a Bosendorfer piano, slamming the lid behind him. For his audition, he paints the town white and Nuremberg quickly finds itself in a collective tizzy.

At the end of Act II, the riot of the libretto becomes art happening with the residents joyously splashing each other with paint from giant Warholesque soup cans, tossing off their wigs and congaing like is 1965 all over again. Even the statues of the great German artists of the past that line the walls of the academy come to life as Bobbleheads Behaving Badly. By the end of the riot, Sachs and Walther rue the artistic high spirits they have unleashed and frantically try to clean things up while Beckmesser revels in his newfound joy of personal expression.

In Act III, this reversal continues. During the “Wahn” monologue Sachs is tormented by visions of the Great Artist Bobbleheads acting up: Wagner himself boinks a dead swan; while another takes a dump while reading the newspaper (SCANDALOUS!) Sachs and Walther, suitably chastised, then dress in proper suits and ties and plot a properly inoffensive entry for the prize competition. The Quintet becomes their saccharine vision of the future for Walther and David’s families. During the orchestral interlude and entry of the Meistersingers, the Bobbleheads revolt once more, tie Sachs to a chair and force him to watch their debauchery.

As they finish, a production team comes out and takes a bow. This is too much for poor Sachs, who frees himself and clears the stage, forcing the renegade production team into a dumpster. He then sets them on fire as the still invisible chorus sings the “Wach auf” chorale. He pulls a statue of a golden stag from this human crucible. A scrim rises to reveal the formally dressed chorus set in bleachers, clutching Bayreuth Festspiel programs.

Beckmesser arrives, in his Bohemian best, eager to demonstrate his creativity. He performs a performance art piece in which he creates a naked Adam out of clay, as one would make a golem. The golem them summons a naked Eve and the two of them pelt the scandalized audience with fruit.

Walther then sings the prize song as a kitschy tableau vivant of knight and damsel is created. The crowd loves it. Walther is crowned the winner and given the golden stag while Beckmesser watches in disbelief.

The stage goes nearly black except for an ominous spotlight on Sachs. He sings his final monologue as statues of Goethe and Schiller rise from the floor to create a Leni Riefenstahl-esque final tableau, demonstrating the regie equivalent of Godwin’s Law which states that any production of a German opera ends up being about Hitler.

While this may seem compelling and thought provoking in outline, the production suffers from the fact that the director didn’t know when to stop filling her cart at the Regie superstore. There are too many other aspects to the staging that distract from her central argument. Why, for example, does Sachs make “shoes” at a typewriter and why do sneakers fall from the sky when Sachs critiques Beckmesser’s song in Act II?

Furthermore, the production robs most of the characters of their interest and motivation. It’s never clear why Walther would ever want to be a Meistersinger and why he would be attracted to the frumpy Eva. Sachs as a kind of monster is an interesting idea, but Katharina doesn’t make him a very compelling villain. Only Beckmesser holds our interest, which is part of the director’s point. In the end the production ends up feeling like an overzealous college application essay, crammed with too many ideas and references, and stymied by its overeager determination to establish prove the writer’s intellectual bona fides.

Musically, the performance is a rather stolid one. Maestro Sebastian Weigle finds neither the poetry nor the conversational quality that others have brought to this score. Furthermore, he is sabotaged by the recording engineers who have created a balance between stage and orchestra that sounds nothing like it would in the Festspielhaus because the orchestra is way too blatty and prominent.

Klaus Florian Vogt as Walther is the biggest star in the cast. He sings with an enviable combination of sweetness and stamina that results in a truly melting Prize Song. One only misses a touch of metal and bite for the character’s angrier outbursts.

The Sachs, Franz Hawlata, barks his way through too much of the part and displays little romantic soul in his more introspective moments. To be fair, the production demands a gruff belligerent Sachs and the perpetual smoking on stage, even with fake cigarettes can’t be easy for a singer.

Eva (Michaela Kaune) and Magdalene (Carola Gruber) were both rather matronly and shrill. Their voices grated rather harshly, but they demonstrated a thorough commitment to the director’s concept.

Michael Volle was mesmerizing as Beckmesser, clearly relishing the opportunity to portray a different take on this character. I would be reluctant to assess his vocal capabilities based on this interpretation, but I would be happy to encounter him again in an opera. The others in the lengthy cast didn’t leave strong vocal impressions.

For this DVD, the producers included closeups and other camerawork that was filmed during rehearsals. This makes for some great images including a shot of burning flames reflected in Sachs’ glasses, but also serves to emphasize that the production placed some critical action at the extremes of the enormous set where it could not have been easy to see. The vigorous booing at the final curtain is preserved as well.

Is this worth buying? I found the performance riveting even if the production was sometimes confounding and overthought. It inspired a great deal of thought and discussion in the days after I watched it and for that I am grateful that I saw this.

Comments