Very few things intrigue me as much as analyzing belcanto operas, comparing their several versions and examining the composers’ second thoughts, modifications and revisions that, willingly or unwillingly, they made to their scores.

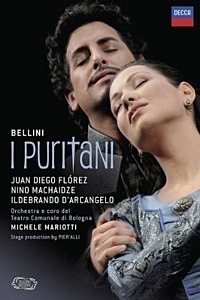

I was already salivating when I heard that the Teatro Comunale di Bologna was going to perform Vincenzo Bellini’s I Puritani in the new critical edition by Fabrizio Della Seta. DECCA, which has released this DVD documenting the 2009 Bologna performances, reports on its cover that this Puritani follows the above-mentioned critical edition, but unfortunately it is not telling the whole truth.

Or rather, while the original intention was to adhere to it, practical reality forced the Comunale to abandon its lofty ideals of performing the opera uncut. Rumor has it that a member of the cast was simply too tired to arrive at the end of the opera unscathed.

The cuts concern mostly the third act. A big chunk of Arturo’s act III romanza is chopped, but it is especially the duettone in the same act that suffers the injury of the scissors: about forty measures are left on the editing floor. To find another studio recording with this same drastic cut one has to go back to the 1952 Cetra release with Lina Pagliughi and Mario Filippeschi. Other smaller cuts affect Elvira’s “Polonaise” and the “duet of the two basses” at the end of Act II.

Compared to the standard Puritani, the only major differences are the reintroduction of a trio in the first act and the finale of the opera. By now everyone is familiar with the rondò “Ah, sento o mio bell’angelo” sung by the soprano, which Bellini wrote for Maria Malibran. In late 1834, while composing I Puritani for its premiere in Paris, Bellini was simultaneously preparing a version to be shipped to Naples, where the Spanish diva was scheduled to sing Elvira: as it happened, Malibran never sang this opera, as the score was halted in Marseille due to a cholera outbreak and reached Naples only after Malibran had left. Obviously this version gives much more space to Elvira.

For the Paris version, where Giulia Grisi and Giacomo Rubini had equal star power, Bellini first wrote the rondò for both soprano and tenor but eventually decided to cut it altogether. This Bologna production, where the main draw is undoubtedly the tenor, restores this finale “ a due”.

Another unfamiliar piece of music that found its way into the critical edition is a trio for Arturo, Riccardo and Enrichetta, to be placed right before Arturo flees with the Queen. This trio, which was excised immediately after the Paris premiere, and is still present in the Naples score, is simply gorgeous, one of the most haunting pieces of music Bellini ever wrote. Slightly reminiscent of another trio, the one for Elvino, Rodolfo and Teresa in La sonnambula, this composition is alone worth the price of the DVD. While the tenor sings one of the typical Bellinian cantilenas, sailing twice up to the high B natural, Enrichetta and Riccardo provide a phenomenal counterpoint, the first expressing joy for the unexpected turn of events, and the latter – in broken snarly phrases – gratified satisfaction.

The Bologna production is a mixed bag of shining jewels and missed opportunities.

It is not one Pier’Alli’s most successful efforts. The producer/set and costume designer has created a mostly dull, only intermittently appealing mise-en-scène, where two colors, blue and grey, dominate, with the except of Elvira’s white bridal dress. The impression is that the leading singers are left to their own devices, while is Pier’Alli’s handling of the chorus is downright ridiculous. All throughout the opera, the female choristers engage in ritualistic gestures, raising their arms, then crossing them on their breasts, then turning their palms against the sky and so on, looking like traffic cops. Particularly execrable is Elvira’s mad scene, with the protagonist surrounded by dark-veiled female mourners holding oil lamps.

The video direction is clearly and inevitably influenced by the Met HD broadcasts, with weird zooming and camera movements on steroids. I personally like it, though it is reasonable to imagine how many viewers will find it utterly intrusive and distracting.

Michele Mariotti’s conducting is simply excellent. The young conductor (born in 1979) brings us in medias res right from the aulic, mysterious Prelude. Almost all the instrumental part is oriented in this direction. He portrays the bronze, gleaming, iridescent color of a civil war, with its sudden storms, its sunny flashes, and the changing mood of the chatelaines and warriors. He is equally adept at highlighting the lyric element of the opera with its ecstatic and dreamy tones as well as at sustaining the dramatic tension, bringing to the fore its epic and chivalric spirit.

In the above-mentioned reinstated trio, he creates a climate of suspension, thus disproving those who claim that this piece halts the action. Having graduated at the Rossini Conservatoire in Pesaro, he is quite familiar with the belcanto practices. All the daccapos are tastefully ornamented, and in one case (Riccardo’s cavatina) some variations are present already in the first exposition. With its malleable orchestra, Mariotti proves especially good at accompanying and supporting the singers, who, in a few occasions, would have not survived without his assistance.

Ildebrando d’Arcangelo (Sir Giorgio), unrecognizable in his white wig and old man make up, is vocally correct, but generally monotonous. With no gravitas, no trace of empathy, no grief, no emotional participation (there is no difference or sense of escalation among “piange”, “s’affanna” “invoca morte”) “Cinta di fiori” becomes an interminable singsong. He looks and sounds uninterested in the role.

The timbre of baritone Gabriele Viviani is rather generic; while he comes to grief in the low register (for instance, in his cavatina he ducks the low A flat in the phrase “per anni ed anni”), his top is easy, almost suspiciously tenorish: the high F on “nella speme” is produced open, whereas even a good tenor should already prepare for the passaggio on that note. His style lacks nobility and elegance. Riccardo may be the villain of the story, but Bellini entrusts him with some of his most melancholy and yearning melodies, where the singer is required to demonstrate his grief and loss through an enormous variety of dynamic signs, which Viviani largely ignores. The agility in the cabaletta is too aspirated and not very precise.

Nino Machaidze’s Elvira is a disappointment. In addition to a monochromatic timbre, she does not possess the technical requirements to sing Elvira. In the act I duet with Giorgio, characterized by a vocal writing heavily influenced by the Rossinian canto di forza, her voice sounds immediately acidulous and glassy in the middle and inaudible in the low register. Her first high notes tend to be shrill (and this duet with all its As flat and As natural hits constantly that area), with the consequence that the sovracuti are open, pinched, almost screamed because she is unable to float them: definitely not a good sign for a such a young soprano (she was born in 1983).

The Georgian soprano does the best she can (which is not much) in the agilità di forza, while her agilità di grazia (the Polonaise) is acceptable. She doesn’t however show much propensity for trills, which are all flattened out. The act I finale, though facilitated because performed without the unwritten but traditional puntaturas to the high Ds, still shows signs of strain above the staff. The voice itself has a certain volume, so much that in the third act Ms. Machaidze systematically covers her partner when they sing together. At the end of the duettone (which is no longer such with all the cuts), the only audible high C is hers.

One cannot shake the suspicion that Ms. Machaidze was largely cast because of her stage presence. Very attractive, with her full lips and perfect nose she has more than a passing resemblance to a younger Angelina Jolie.

Ça va sans dire, if DECCA has released this DVD, it is only because of Juan Diego Florez, whose performance proves why I Puritani has been so far marginal in his repertoire. Before this Bologna production, he had performed it only twice, in Las Palmas (2003) and Vienna (2004).

Florez, a proficient and accomplished technician like few others, is by his nature a few sizes too light for Arturo, a role he sings because it’s a part that the star system requires from those who aspire to be bona fide belcanto superstars, but his hunting ground is Rossini (the roles written for Giacomo David and especially the opere buffe) and some limited Donizetti. He has incredible facility in his upper register, and his delivery is elegant, clean and tasteful.

He gives his best in the cavatina “A te o cara” (unfortunately marred by the soprano’s pertichini, as she can’t quite float those long high As), with an impeccable legato and a secure high C sharp. When the situation gets less lyric and more heated, as in the recitative with Enrichetta and the confrontation with Riccardo, things become rougher. Phrases like “Non temo il tuo furor…ti sprezzo” take him to his limits: instead of showing defiance and courage, he risks sounding querulous.

The big act III romanza, albeit opportunely shortened, lies too low for him and he quickly tires. In the whole act (which, as mentioned before, has been considerably cut), Florez gives the impression of playing defense, mastering his resources for the big excursions to the top. In “Credeasi misera”, he omits the first written D flat along with a dozen measures, so as to jump directly to the next D flat, which replaces the famous, or infamous, F natural. Both tenor and soprano sing the rondò together, capping it with a high E flat, with Machaidze once again submerging Florez.

The overall impression is of a tenor who shows significant tiredness and survives only because of his iron-clad technique. Speaking of Luciano Pavarotti’s Radames, Mario Del Monaco said it was as if Nemorino had lost his way and somehow ended up in Thebes. In Florez’s case, one could say Lindoro is wandering around Plymouth.

Comments