To get straight to the point, the main attraction of this DVD is Renata Scotto.

The Italian soprano, the first to perform all three heroines of Il trittico at the Met, is simply superb. She has élan in the moments of tension and a powerful, in-depth delivery. There is not a single word in the entire work that Scotto lets go to waste. Hers is a play of colors and gradations prodded by an exceptional imagination and interpretative sensitivity.

Add to this an eloquent, aristocratic, full-relief pronunciation, which coalesces with the pliability of her sound and the refinements of the nuances and the result is nothing short of brilliant.

In Il tabarro, it is sufficient to listen to the subtle irony mixed with a hardly concealed resentful boredom that Scotto slips in a simple phrase like “Ti sembra un gran spettacolo?”, while in the duet with Luigi she successfully combines the feverish and desperate abandon with anxiety and bitterness. Even more outstanding is the scene with Michele, introduced by a “Com’è difficile esser felici” that in its own syllabic course on an orchestral void could be nothing more than a conversational phrase, but is here transformed into a pivotal moment by her suffocated, intense, tragic phrasing.

Scotto’s flawless legato and breath control allows her to spin and modulate the sound in long sentences. Her rare ability to “caress” a phrase makes Giorgetta’s sexual tension and frustration thoroughly palpable. In contrast, in the finale of Suor Angelica, the soprano purposely makes her vocal production threadlike and trembling, as if crossed by the electric discharges of a febrile and haunted overexcitement.

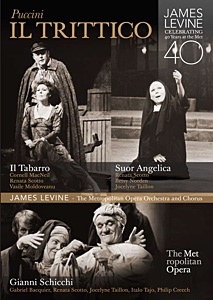

This Trittico (part of James Levine: Celebrating 40 Years at the Met – DVD Box Set) demonstrates that Scotto’s instrument in this period of her career was not as tattered and worn as legend (and her detractors) would have it. In Il tabarro the control of the voice is irreproachable, with a secure strong top, including a high C that shows no sign of stridency.

“Senza mamma” is remarkable for the length of her breaths and floating sounds. Only the climax in the phrase “Muoio per lui, e in ciel lo rivedrò” turns out a bit abruptly short. In general, she sounds in much better voice than in her 1976/77 recordings of Il tabarro and Suor Angelica under Lorin Maazel.

Her Lauretta in Gianni Schicchi is less convincing for a number of reasons: she tends to play grand diva in a role that demands extreme simplicity, and paradoxically, she sounds less at ease from a mere vocal point of view. Both she and her Rinuccio (Philip Creech) eschew the optional high note at the end of their duettino. Personally, I couldn’t care less about Lauretta, after such devastating, sublime portraits of Giorgetta and Angelica.

Cornell MacNeill, who had sung both Michele and Schicchi when this production was inaugurated in 1975, now appears only in the first panel of the triptych. He is not much of an actor, but he is still in good voice and delivers a solid performance. Gabriel Bacquier’s undoubtedly diminished vocal resources are still sufficient for a role like Gianni Schicchi, where he is able to display his histrionic talent.

Bianca Berini is exquisite as Frugola, with a dark, robust voice, true mezzo at ease in the difficult tessitura of “Ho sognato una casetta”. She is a throwback to the not so ancient times when true Italian mezzos were roaming the earth. She also sang the role of the Princess in Suor Angelica on opening night and in a few subsequent performances.

Regrettably, for the telecast the Met opted to assign the latter part to Jocelyn Taillon, whose voice sounds divided in three disconnected sections, with a booming chest register, a throaty middle and a short top. There is not a single interpretative idea; her fraseggio proceeds heavy, monotonous and unable to give shape to any kind of character.

Next to her, Scotto murmurs “Dopo sett’anni son davanti a voi”, and she makes you physically feel all the weight of her reclusion, which she has not been able to accept, but which she suffers with the firmness and dignity of an aristocratic woman accustomed to translate the flood of her feelings into a composed, self-possessed language: it is her noble lineage, as a matter of fact, the key to understand Angelica, the only leading character in the Puccini canon to belong to the European high aristocracy.

Vasile Moldoveanu is a solid Luigi. Although the color and timbre of his voice are not particularly memorable, he survives the role’s murderous tessitura with all its high G sharps and As, nailing the devilish acciaccatura on the B natural where most tenors strangle themselves.

With all the bad press he was receiving at the time, I was prepared to hear the worst from Philip Creech but I must say to the contrary that he gives quite a good rendition of the role of Rinuccio, another part often overlooked and taken for granted, but which is in fact presents its good share of traps.

Among the comprimari, only Charles Anthony as Tinca and Gherardo, and Italo Tajo as Talpa and Simone stand out.

James Levine’s conducting is impeccable in his choice of tempos and he successfully captures the atmosphere of each opera. His color palette is wide and rich, the rhythm of the narration unaffected and incisive. Only a very critical listener might observe that at times Levine confers to some orchestral expansions a magniloquence somewhat disproportionate to the events, which are not exactly those of Götterdämmerung.

Fabrizio Melano’s production is hyper-realistic, traditional, not infrequently dull and ultimately inoffensive, except for a blatant anachronism in Gianni Schicchi: in 1299 Palazzo Vecchio was just being built and Brunelleschi’s dome was 130 years in the future. One would thought have a stage director would know this.

Reach your audience through parterre box!

parterre box, “the most essential blog in opera” (New York Times), is now booking display and sponsored content advertising for the 2023-2024 season. Join Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Warner Classics and many others in reaching your target audience through parterre box.

parterre box, “the most essential blog in opera” (New York Times), is now booking display and sponsored content advertising for the 2023-2024 season. Join Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Warner Classics and many others in reaching your target audience through parterre box.

Latest on Parterre

Merry Widow | Finger Lakes, NY | July 25-28

Geneva Light Opera’s production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow will feature prize-winning baritone Bryan Murray and soprano Alexis Olinyk in the superb acoustics of in the landmark Smith Opera House in Geneva, New York on July 25, 27, and 28. A small city on the north end of the largest of NY’s Finger Lakes, Geneva…

Geneva Light Opera’s production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow will feature prize-winning baritone Bryan Murray and soprano Alexis Olinyk in the superb acoustics of in the landmark Smith Opera House in Geneva, New York on July 25, 27, and 28. A small city on the north end of the largest of NY’s Finger Lakes, Geneva…

parterre in your box?

Get our free weekly newsletter delivered to your email.

Comments