The three Brownies applying the final touches to a tapestry – the show curtain – depicting an idyllic landscape of Windsor before the music begins are the first indication that this production

of Falstaff does not take place in Elizabethan times.

Sir John Falstaff, who lives in a Tudor-style Garter Inn dominated by a huge portrait of George VI, dons a sort of safari suit for his amorous rendezvous, suggesting his involvement in some recent colonial war. Mistress Quickly is an Auxiliary Territorial Service lesbian, and Fenton an American GI Joe, adding another reason to Ford’s dislike of him. After all, post war Europe was swamped with American soldiers playing fast and loose with European girls, especially a bobby-soxer wannabe like this Nannetta.

Richard Jones’ updating of the story to the late 1940s makes sense; both Shakespeare’s and post-war England were periods of growth, in which the old class system was still standing, challenged by the nouveau rich.

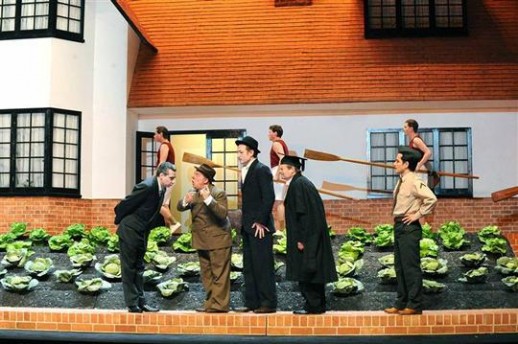

The production, with sets and costumes by Ultz, looks magnificent in its clarity, marvelous colors and extreme attention to the smallest detail. This being Windsor, there are plenty of Eton schoolboys, young men in rowing tank tops, and Girl Guides roving about.

The only problem I find in this production is the toning down of the class conflict, such a crucial hinge in both the play and the opera. Falstaff’s superior social status is here barely noticeable. He looks less grotesque than in most productions, blending more with the people who surround him, but this happens at the expense of one of the key elements of the comedy, the gap between Falstaff’s sense of self-superiority and the antipodal perception that the outside world has of him.

Falstaff is an all ensemble opera, and the cast is as close to perfection – at least visually –as it gets. Every character looks his or her role, showing naturalness and fluid spontaneity in their interactions. This production, like well-rehearsed choreography, runs like clockwork from its inception to its very last note.

Towering above the ensemble is the protagonist, Christopher Purves. Already a remarkable Ford opposite Bryn Terfel’s Falstaff, Mr. Purves auspiciously progresses now to the title role for the first time, displaying a lyric baritone with an aristocratic, musical phrasing, and sounding at ease throughout his range, with a particularly effortless top. With the complicity and guidance of the director as well as an extraordinary make up (I’ve hardly ever seen such a realistic fat suit), he creates a less clownish, freakish Falstaff than usual.

The rest of the company ranges from the good to the merely competent, without extremes in either direction. Peter Hoare opens the opera with an uncommonly rich and ringing Dr. Cajus, while Tannis Chrystoiannis’ woolly baritone is slightly unfocused as Ford. Charming is the adjective I would use to describe Adriana Kucerova’s Nannetta; her beau, Bulent Bezdü (Fenton) makes up for a lack of ardor with a pleasant tenor comfortable in spinning pianissimos in the upper register. I found Dina Kuznetsova’s vibrato too obtrusive and wayward for what is basically a role (Alice) that should blend in with the others.

In addition to Mr. Purves, the only other stand out was the Mistress Quickly of Marie-Nicole Lemieux, whose booming contralto and baritonal chest notes never fails to win the loudest laughs.

Vladimir Jurowski’s conducting of the London Philharmonic is technically beyond any criticism; his orchestra is pure, crisp, unblemished down to the last instrumental minutiae. He maintains complete, tight control of the balance between stage and pit, no easy task in this opera. What I found missing in his exceedingly analytic approach is tenderness, affability, melancholy, empathy. A Falstaff without joie de vivre is not quite Falstaff.

Comments