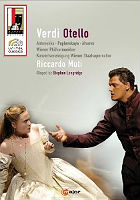

A dramatic symphony with incidental voices: that’s how Riccardo Muti’s Otello

, which inaugurated the 2008 Salzburg Festival, could be aptly described.

Beginning with the initial allegro agitato with its piercing lashes, it instantly appears obvious that Muti’s intention is to go for the jugular, nail the audience to their seats and never give them a moment of relief. The raw energy emanating from his orchestra is simply overwhelming, often brutal. There is no denying that such an aggressive approach to the opera can be electrifying and breathtaking.

Even the most jaded and knowledgeable audiences will let themselves be carried away in this paroxysmal orgy of sound. Then comes the moment when the adrenaline dies away, your senses become tranquil, and you slowly comprehend that what have you just heard was not exactly Giuseppe Verdi’s opera. Score in hand, you realize that Muti’s dynamics range from ff to ffff, and Verdi’s meticulously annotated metronomic indications are almost consistently disregarded, favoring frenzied, convulsive tempos.

One cannot help but notice Muti’s primary virtue: to maintain an extremely clean, crisp, precise orchestral sound despite his breakneck pace. That the orchestra is the Wiener Philharmoniker undoubtedly helps, though it must be noted that this is something the Italian maestro normally obtains with much lesser orchestras as well.

I am thankful to Maestro Muti for choosing the third act concertato as revised by Verdi for the opera’s Parisian premiere in 1894. It is well known that Verdi was unsatisfied with the original version of this ensemble, the most monumental he had ever written; he felt it lasted too long, dragging the action. For the Paris production he decided (a recurrent theme throughout his career) to immolate musical complexity on the altar of dramatic intelligibility.

He allotted more space and prominence to Iago, who is now able to continue his machinations exchanging frantic bits of dialogue with Roderigo and Otello, resulting in more clarity for the audience. It remains a mystery why, although pleased with the revision, Verdi failed to incorporate it in the subsequent Italian editions of the score, thus condemning it to its semi-rarity status.

Even the biggest, titanic voices would have problems battling the wall of sound emanating from the podium. When the singers are mere mortals, they don’t stand a chance.

Thirty-three year-old Alexandrs Antonenko, personally chosen by the Maestro, dimly sounds to have a budding Otello voice hidden somewhere, but it easy to understand how easily he could have come across as underpowered in the Salzburg live performances, his attempts at vocal subtlety and finesse mostly frustrated.

The baby-faced Latvian tenor also looks too young for the role, and no attempt was made to make him look older. In my opinion, when the racial element and the difference in age between Otello and Desdemona are toned down or eliminated, it becomes more problematic to understand the Moor’s insecurities and inferiority complex, which are the origin of the drama.

Marina Poplavskaja possesses a sizable, full lyric instrument marred by a noticeable rigidity and lack of ring in the high register. My impression is of a soprano who has not yet learned to properly handle the passaggio. She is more passionate and resolute, less simpering than most Desdemonas; however, the key word for the role is “dolcissimo”, and a soprano in distress floating above the staff will be unable to meet most of the part’s demands.

Carlos Alvarez portrays a visually superlative Iago, but his interpretative intensions are not backed up by his current vocal conditions. Verdi requires Iago to express his sly deviousness by having the baritone sail through a very high register studded with pianissimos, which Alvarez, whose instrument has become dry and parched, has problems negotiating. I have almost given up my quest to find a baritone able to execute the many mocking trills Verdi wrote for this part.

One could not imagine a better Cassio than Stephen Costello, who has the right youthful voice and winsome looks for this small but crucial role.

Rumor had it that Maestro Muti autocratically handpicked the team responsible for the visual part of the show. Stephen Landridge’s production was greeted with a storm of boos on opening night; obviously, this unsavory moment is not shown in the DVD.

I can understand the reasons this production also gathered mostly negative professional reviews, but I do not share their ferocity. In a way, it is a non-production, where the main actors are given only vague generalized instructions, and whoever has the best instincts (Mr. Alvarez) manages to create a character, while those with less experience are left to their own more limited devices.

The only moment of pure theatricality occurs when, during the music following the “Ave Maria”, a spotlight reveals Otello’s face in a corner, creating a horror movie style effect, with the presumption that he had been lurking there all along witnessing his wife’s despair. Far less felicitous are other expedients, such as the stage business concocted during “Fuoco di gioia”, when three very scantily clad prostitutes try to obscenely seduce a young boy. (Why is it that prostitutes in opera seem to always come in threes?)

Austere, unadorned galleries encircling a glass catwalk provide George Souglides’ single set, to which other elements are added in each act, like the second act beautiful Veronese style portraits. Emma Ryott’s costumes are on the other hand are sumptuously old-fashioned.

This Otello was meant as one-man show and ultimately that is precisely what it turned out to be.

Comments