In short, the Massachusetts greenery was set for a model Goliath v. David showdown: the renowned Tanglewood headliners versus the baby opera company and its disproportionate ambitions. As critics and Rusalka enthusiasts descended upon the outdoor Koussevitsky Shed, naturally your trusted correspondent was all in it for the underdog.

“We have a lot of competition,” acknowledged BOF co-founder and general director Jonathon Loy, eyeing the empty chairs on opening night.

But Loy needn’t fret. For what he and his co-founder, musical director Brian Garman, have pulled off in Pittsfield is some true wizardry—a three-night bravura production with a top-shelf, enthusiastic cast (particularly the women, the composer would have been pleased to hear) that both understood and amped up the full screwball enchantment of the score.

Strauss’ 1915 chamber comedy is a classic mise en abîme. A wealthy arts patron has commissioned a dilettantish double bill, one serious opera about the doomed and island-bound Ariadne (Marcy Stonikas) and one bit of commedia dell’arte featuring a troupe of Italian players like Zerbinetta (Nicole Haslett) and Harlekin (a delightful Samuel Schultz). In one night, the two works are to be performed consecutively—yet we’re running out of time, and so now the two works must be contracted into one, comedy and tragedy, all presented begrudgingly on the same stage at once.

Mayhem and hilarity—as well as the requisite, maundering soliloquies on love and art by regular Strauss words guy Hugo von Hofmannsthal—ensue! Although in this generally straightforward rendition, a traditional approach is given priority over great leaps of interpretive faith. The stage is subdivided with the small orchestra on the left, and a multi-tiered platform on the other side to allow the action of the prologue—mainly the petty squabbles of the Composer (Adriana Zabala) with the comedians—to unfold in a topographically interesting way.

For the opera’s second half, sets by Stephen Dobay are simple but attractive, with a stalactited cave and crescent moon marooning us among the nymphs and divinities of the island. Lighting by designer John Froelich (a resident for the Met since 2012) was also particularly inspired, adjusting humorously, for instance, to play up the Composer’s romantic visions of his characters’ transformations in the production’s first act.

Aside from a few historical notes by Michael Kennedy on the work’s troubled history (Strauss and von H couldn’t quite settle on a story to follow Rosenkavalier), the program offers regrettably little insight on Garman and Loy’s more reformist choices.

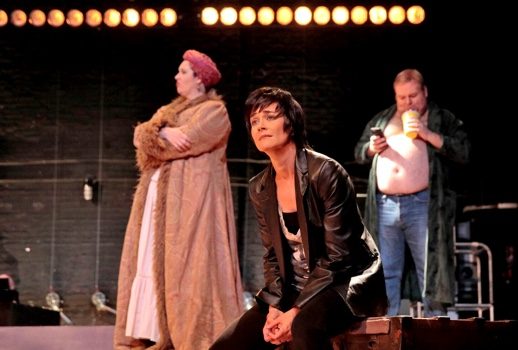

As a viewer, I wish I could have learned why, for example, the creative team felt the need to interpolate an English-speaking Trump-like figure to play the “Producer” of the fictional opera (hammy Chuck Schwager giving us his best “this show is gonna be the biggest!”); or why, despite the imperial traditionalism reserved for the island divinities and commedia characters in this telling (all skillfully costumed in period wear by Charles Caine), we also needed to see the Tenor playing Bacchus on a cell phone? Ariadne auf Massachusetts, indeed.

This production was a knockout on both counts—but in more specific terms, what worked so especially well were the singers’ winking, sidelong performances. In roundly terrific voice and exceedingly well cast, these players knew how to milk the composer’s ironic intentions, and never shirked putting the melodrama (and the infamously strenuous vocal writing) in scare quotes.

As the prologue’s Komponist, mezzo Zabala flung herself into her role, dialing up the parodic elements of the composer as navel-gazing solipsist, and mooning conceitedly over her score in the black leather jacket of a misunderstood hipster-artiste.

Those playing the vaudevillians in this production were given the perennially difficult task of making a jaded American audience laugh at wocka-wocka slapstick routines that now feel, well, more than a little quaint. Chalk it up to post-modernity and the talents of this cast that we can now giggle anew at pratfalls, pies, and teddy bears. Easy-voiced tenor Spencer Viator, a recent Ferrando for LoftOpera, earns special mention for his turn as Brighella—I look forward to more from him in the future.

Re: Zerbinetta. With her Clara Bow face and Rita Streich demeanor onstage, Haslett was ravishing, an ideal soubrette. Her “Großmächtige Prinzessin” was suitably arch, set-chewing, and crisp—yet despite her ease with the tessitura, she made insurgent comedy of the aria’s long and motormouthed licks, as if to jokingly communicate that the thing’s really an aesthetic monstrosity, no matter how conquerable it may appear.

As the despondent Ariadne she must cheer up, Stonikas alone should be reason enough to visit this production. My co-attendee and I cried out in unison when she started singing from her recumbent position on the rocks, mourning Theseus, with perfect messa di voce, a free and even top, and a “Du wirst mich befreien” in her big act two aria that needed no superfluous gulp of air. Providing her divine counterpart in the role of Bacchus, tenor Kevin Ray wasn’t quite so secure, but had a glorious ringing tone certainly worthy of the role.

If traveling to the Berkshires and having to select between two performances in one night, and then opting for Ariadne auf Naxos (a trifle about dueling shows) feels like some kind of coincidence, please trust that the irony wasn’t lost on me. Suffice it to say that if Tanglewood is where the so-called “serious” work is to be found, I guess I’m just glad I stayed in Pittsfield for the commedia.

Photos: Ken Howard

Comments