The West Coast Premiere of the operatic adaptation of Atwood’s landmark 1985 novel The Handmaid’s Tale finally landed spectacularly at the War Memorial Opera House stage on Saturday, September 14th, four years after it was supposed to. Written by Danish composer Poul Ruders with a libretto by British actor and writer Paul Bentley, the opera – then to be conducted by Thomas Søndergård and starring Sasha Cooke as the handmaid Offred – was intended to be one of the operas for the Fall season 2020-21, which subsequently was canceled due to COVID-19 pandemic. Our world dramatically changed alongside those plans in that four-year window!

Set in a near future dystopian New England where a radical group called “Sons of Jacob” topples the United States government and creates a totalitarian theonomic state called The Republic of Gilead, Atwood’s novel chronicles the harrowing plight of a “Handmaid,” a fertile woman who were forced to bear children for the “Commander,” the ruling class. In the Republic of Gilead, women become the lowest-ranking class as they are prohibited from owning money or property or reading and writing. The novel is written from the first-person point of view of a handmaid known simply as Offred – yes, “of” Commander “Fred.”

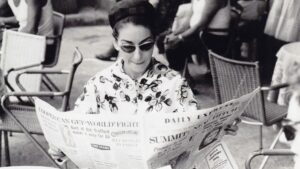

Since its publication, Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale has been adapted for various stages and screens, including the 1990 film starring Natasha Richardson as Offred, a 2013 ballet by Lila York, and most significantly, a popular and long-running Hulu series led by Elisabeth Moss. In an interview with SF Opera General Director Matthew Shilvock, Atwood detailed how she agreed to an operatic adaptation:

“I was in Copenhagen doing book promo, and the tall Danish composer, Poul Ruders, went down on his knees to me on the bright red carpet of the Hotel d’Angleterre. He said, “I’ve been given a commission by the Royal Danish Opera Company – the first one they’ve given in 34 years. I have to do The Handmaid’s Tale! I must do The Handmaid’s Tale! If I can’t do The Handmaid’s Tale, I don’t want to do any opera at all!” I thought, “Either this man is a lunatic and the opera will be bad and will disappear, or he is a visionary and a genius, and it will be good. What’s to lose? Roll the dice!” And so I did.”

Ruders’s opera was premiered at the Royal Danish Theatre in Copenhagen on March 6th, 2000, conducted by Michael Schønwandt and directed by Phyllida Lloyd, starring Marianne Rørholm as Offred. Ruders translated Bentley’s English libretto into Danish for that premiere (called Tjenerindens Fortælling), and the performance(s) were subsequently recorded on Dacapo, the only complete recording of the opera. So far, the opera has traveled to the English National Opera, Minnesota Opera, Canadian Opera Company, Yarra Valley Opera Festival (Australia), Boston Lyric Opera, and Glow Lyric Theater (Greenville, South Carolina), the latter two in a reduced instrumentation. Ruders also created Offred Suite, where he compiled five of Offred’s arias interwoven with orchestral interludes from the opera plus the postlude for full orchestra. It was recorded on Bridge Records, together with his Tundra and Symphony No. 3 Dream Catcher, by Odense Symphony Orchestra conducted by Scott Yoo and featuring soprano Susanna Phillips (the Suite would make a great introduction to the sound world of this opera!).

In the 2017 Introduction to her novel, Atwood detailed her creation process in writing the book: “One of my rules was that I would not put any events into the book that had not already happened in what James Joyce called the ‘nightmare’ of history, nor any technology not already available. No imaginary gizmos, no imaginary laws, no imaginary atrocities. God is in the details, they say. So is the devil.” Stephen Johnson, in his exceptionally illuminating write-up for the Dacapo liner notes, contrasted the difference between the opera and the novel:

“The book has a strongly polemical thrust. It was clearly conceived as a warning: if we aren’t very careful, something like this might happen to us. If that sounds implausible, one only has to change the religion and the continent to see that something like the Republic of Gilead has already happened – in Iran (mentioned in the Professor’s lecture) and in Taliban-dominated Afghanistan. Ruders was well aware of these ominous developments when he began work on the opera in 1996. The trouble is that opera is a very bad medium for preaching; novels make much more effective tracts. Opera’s natural territory is human emotions – preferably the most basic human emotions. […] From this seemingly unpromising material, Paul Bentley fashioned a triumphantly operatic libretto. Close as it is to the spirit […], the libretto condenses and reorders the contents so that we see and hear two powerfully affecting tales enacted simultaneously, both moving towards catastrophe with tragic inevitability. By casting two singers in the role of Offred, the opera allows us to follow both her life in the traumatic days leading up to the fundamentalist revolution, and her struggles to survive and make sense of her experiences in the horrific environment of the new regime.”

San Francisco Opera’s production of The Handmaid’s Tale is a co-production with the Royal Danish Theatre, directed by John Fulljames, the previous Royal Danish Opera Director. It premiered in Copenhagen on October 29, 2022, conducted by Jessica Cottis and starring Hanna Hipp as Offred. Unlike the 2000 premiere, this time, it was performed using Bentley’s English libretto.

The most prominent defining feature of Fulljames’s staging was its cutting of both the Symposium Prologue and Epilogue. While changing the novel’s first-person account into a third-person opera, Ruders and Bentley bookended the opera with a framing device, an international video conference in the year 2195 with the subject of “Iran and Gilead: two early 21st Century monotheocratic states,” where Professor James Darcy Pieixoto was seen giving a lecture in the beginning, titled “Problems of Authentification in Reference to The Handmaid’s Tale,” before showing up again, in the end, to tell that the ultimate fate of Offred and the men in her life was unknown. The effect, almost similar to the framing of One Thousand and One Nights, distanced the audience from the atrocity of the story, primarily since the whole texts were meant to be a reconstruction of a 200-year-old text from multiple cassette tapes. The novel also refers to a similar setting only at the very end (“Historical Notes”), making it almost like a surprise ending to the book.

By cutting such a framing device, Fulljames shoved the audience right smack into the world of Gilead (which setting he moved to post-America in 2030 with flashback memories of “the time before”) without any way of escaping it. Considering in the last four years, women (in the US) have lost the Constitutional right to abortion, the book banning in the US states has reached fever pitch, and we’ve got a politician that wanted to give more voting rights to parents, the Gilead nightmare isn’t just a mere academic study. It feels more like a reflection of where we were heading if we were not careful. Little wonder that my opera companion that night, who wasn’t a big opera fan in the first place, quipped that the show gave him a lot of food for thought!

A master of orchestration, Ruders created a score of both excruciating agony and exceptional beauty, all while moving with such a thundering power and relentless intensity to match the nature of the story. It didn’t make for comfortable listening, but that’s probably the point. Employing a large orchestra and utilizing a wide array of instruments (including a sampler keyboard, digital piano, and organ) plus colossal percussion sections, Ruders’ sound world was decidedly sterile, icy, and metallic (Johnson above dubbed him “the Richard Strauss of the computer-age orchestra.”). Vocal lines, too, were primarily narrative rather than lyrical, although, as the Offred Suite above demonstrated, there were tender moments in Offred’s aria and half-arias, and especially in the climactic duet of both Offreds in Act II, where they both grieved the loss of her daughter. Nevertheless, the repetitive chant-like choruses of the Handmaids dominated the score, never for once letting the audience forget what kind of world Gilead was! Furthermore, his “twisted” Ivesian treatment of the hymn Amazing Grace – during the impregnation rituals and love-making with Nick, the Commander’s servant – cleverly highlighted the irony and hypocrisy of such actions!

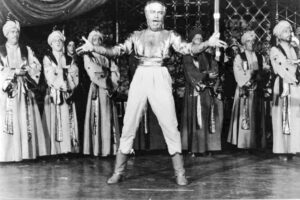

Repetition seemed to be the key to Fulljames’s direction, and he used it effectively. Everything and everyone in the Gilead world moved in formation and with military precision. In contrast, everyone ran free in “the time before” flashbacks, clearly delineating the two worlds apart as the story moved back and forth. Only during the sinful times at Gilead—like during Offred’s secret visits to the Commander and Jezebel’s scene— were the lines blurred, and the actions happened freely, albeit cautiously.

Similarly, Chloe Lamford pursued repetition in her unit set design for the show. Lamford, who dazzled with her cube design for Innocence last Summer, designed specific scenic “walls” from the ceiling to denote particular locations: the wall with the Gilead’s Eye for Gilead places, a partitioned glass wall for Commander’s house, an empty white wall with a projection of windows (designed by Will Duke) for the gymnasium/Red Centre. The rest of the set pieces were wheeled from stage left and right, resulting in smooth and well-coordinated transitions for the nonstop actions. Fabiana Piccioliclearly distinguished her lighting for Gilead and “the time before:” bright (mostly) white light for Gilead, and sepia colors for the other. Sound designer Rick Jacobsohn completed the creative team with the arduous task of mixing the sound, as all principals and chorus members on stage, together with the electronic keyboard in the pit, were amplified.

Care must be taken when adapting The Handmaid’s Tale, as the costumes, particularly the colors, are essential to the story’s iconography. The debuting designer Christina Cunningham detailed her process in an SF Opera blog, where she mostly followed the prescribed colors from the book (red for the Handmaids, blue for the Wives, etc.) while ensuring the practicality of such costumes on stage. Of utmost importance were the “wings” headdresses, as the singers had to be still able to see the conductor and each other while wearing them. Cunningham decided to adopt a small bonnet underneath the headdress with broad upward wings fastened by a magnet system, and on stage, they truly made an impressive, albeit not conventional, look. She also favored dull green for the Aunts (instead of brown as in the novel) to “emphasize the militarization of their authoritarian rule.”

As impressive as the production on the stage was, the musical aspect elevated the performance to the highest level. First and foremost, the respect and care of everyone involved in the subject material were so evident that it ultimately made for a thrilling experience for the audience. The conductor Karen Kamensek was the prime example of this. In an interview, she admitted that “[i]t’s a story that must be told, and we are storytellers.” Furthermore, she recognized that “[i]t’s scary for everyone with the subject matter, the sound world. And the sound effects that Poul uses disorient people. […] So I’m trying to find the pulse and the heartbeat of the piece in a way that, just aurally, people can grasp. It is not easy music to grasp, but it is telling the story beautifully.”

Kamensek was essential in finding the “heartbeat of the piece,” so to speak, from the avalanche of sounds generated on stage and in the pit. She moved the story forward with a steady hand, not only by confidently directing the vast ensemble but also, more importantly, by providing clarity and grandeur to Ruders’s score. She coaxed a literal wall of sound from the Orchestra while keeping the tender moments sweet and heartfelt. Furthermore, she brought out the cinematic elements of the score, greatly assisting the actions on the stage.

The Handmaid’s Tale is essentially an ensemble cast, with 19 principals besides the Chorus, most of whom only sing a line or two throughout. SF Opera assembled a superb cast from top to bottom – most of whom were making their role debuts – to bring the tale alive. As the one villain of the story, Aunt Lydia, soprano Sarah Cambidge – the one singer who returned from the announced 2020 cast – was a revelation. Ruders assigned a devilishly high-flying coloratura for the role, and Cambidge performed it with aplomb, coupled with sadistic grins and exaggerated swagger.

The Commander’s household was led by bass John Relyea (returning to the War Memorial stage after 14 years) and debuting mezzo Lindsay Ammann as his wife, Serena Joy. Relyea’s grainy voice projected a warm, caring persona while Ammann’s icy demeanor – both vocally and acting-wise – betrayed Serena Joy’s desperation for a baby to keep her status. Local favorite Sara Couden finally made her SF Opera debut with her compassionate take on the maid Rita, and the always dependable tenor Brenton Ryan excelled as the Commander’s servant and may-or-may-not Mayday sympathizer Nick.

Adler Fellows (2019-21) Simone McIntosh and Christopher Oglesby made a handsome couple in “the time before” as Offred Double and her husband, Luke. McIntosh was particularly heart-wrenching in the duet, as mentioned earlier, with Offred in Act II. Last year Adler Fellow Gabrielle Beteag colored her performance as Offred’s Mother with sufficient cautiousness, while current Adler Caroline Corrales gave a spunky and brave take on Moira, Offred’s rebellious friend. Another outstanding ex-Adler was soprano Rhoslyn Jones, who stately personified Ofglen, Offred’s shopping companion who was part of the Mayday resistance. The SF Opera Chorus, directed by John Keene, sang, chanted, and marched in unison on stage.

Nevertheless, the success of any adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale lies with the titular role, here performed by mezzo Irene Roberts. Roberts, who in an interview admitted that the role represented a daunting challenge that she “would need to look after herself when not in rehearsal in order to withstand the emotional toll of the piece,” truly gave her all to embody the handmaid Offred, both in her voice and in her mannerisms. The dark, gritty tone of her sound imbued the role with extreme sadness yet determined perseverance, and her over-cautious body language rounded out her interpretation of the role. It was hard to take my eyes off her since she was such a presence onstage, and yes, she was there the whole time. The role, as depicted in this production, was highly physical – with high levels of horrific and explicit events like rape and violence – that she performed without hesitation. It was indeed an outstanding tour de force of a performance!

The San Francisco Opera achieved a spectacular feat with this production, and I would like to congratulate everyone involved for providing such essential food for thought for the community. Only six more performances remain, including the live stream on Friday, September 20th, at 7:30 p.m. PDT.

I’ll leave you with the concluding quote from Atwood’s Introduction:

“In this divisive climate, in which hate for many groups seems on the rise and scorn for democratic institutions is being expressed by extremists of all stripes, it is a certainty that someone, somewhere […] are writing down what is happening as they themselves are experiencing it. […]

Will their messages be suppressed and hidden? Will they be found, centuries later, in an old house, behind a wall?

Let us hope it doesn’t come to that. I trust it will not.”

Photos: Curtis Brown

Comments