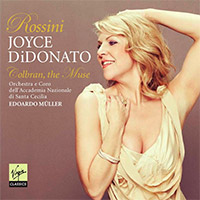

Joyce Di Donato‘s latest release is a CD entirely devoted to music Rossini composed for his first wife, Isabella Colbran, one of the most celebrated divas of the early 19th century.

In recent times, there has been disagreement whether Colbran was a soprano or a mezzo-soprano. She called herself a soprano, but in those days the distinction was only between sopranos and contraltos; the mezzo-soprano category was to be invented later in the century.

In modern performances, however, the problem remains whether the Colbran operatic roles (a total of ten, plus four cantatas) should be entrusted to a soprano or a mezzo. In my view, since they differ in tessitura, extension and character, a few are best tackled by sopranos, but most are better served by lower voices.

The average opera listener may think that “Bel raggio lusinghier” was composed for a very high soprano, because the most famous interpretation of this aria have often been transposed and/or laced with stratospheric variations, which have little in common with what Rossini actually wrote (the aria goes up only to a A).

Armida has the highest tessitura (it goes up to a high C, although not sustained); La donna del lago and Elisabetta, regina d’inghilterra are probably the lowest-lying. The title role of Ermione requires vocalism of verismo intensity; Elena (La donna del lago) on the contrary calls for a gentle lyricism with almost no trace of coloratura di forza.

When Rossini first heard Colbran in 1806, he was 14 and she 21. In that year critics reported her extension ranged from a G3 flat to a E6 flat. However, what is certain is that by the time Rossini started writing for her (Elisabetta in 1815), the artist had lost her sovracuti and was not even comfortable with a high C. Rossini, with the partial exception of Armida, tends to concentrate her music in the middle range.

In addition to the ten roles expressively written for her, Colbran sang three other Rossini operas, La gazza ladra, Torvaldo e Dorliska, and most importantly, Tancredi, where she chose the contralto title role over the soprano role of Amenaide.

This long preamble serves to explain why in the modern Rossini renaissance a significant number of mezzo-sopranos have tackled some of the Colbran roles, most famously Frederica Von Stade (Otello and La donna del lago), Jennifer Larmore (Elisabetta) and Sonia Ganassi (Ermione).

For Colbran, the Muse, DiDonato, who has made a name for herself in Rossini’s opere buffe, turns tragedienne and presents excerpts from Armida, La donna del lago, Otello, Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra, Semiramide and Maometto II. It should be noted that Ms. DiDonato, unlike many other celebrated “sopranos in disguise,” is a true mezzo-soprano. Her vocal center and color is that of a mezzo-soprano.

The music from Armida is the most fiendishly virtuosistic. DiDonato opens her program with “D’amore al dolce impero” — in which Rossini concocts every possible vocal trick : chromatic scales up and down, triplets, trills, and so on — with impeccable, clean agility and an optional, but expected, high C so bright and secure most sopranos would kill for it. She succeeds in depicting Armida’s sensuality without being excessively, languid, mannered or coquettish. Her attacks are exact and precise: just listen to the way she attacks “di smalto ha in core il petto.” She shows no hint of scooping.

The finale to this opera (the closing aria on the disc) calls for Armida to unleash her furor in a high tessitura, and Ms. DiDonato, in full take- no- prisoner mode, sounds like a wounded tigress. After such a performance the writer now wishes that she donned the vest of the sorceress in the upcoming Met Armida.

The mezzo-soprano excels also in more cantabili pages, such as “Mattutini albori” (La donna del lago) and “Giusto ciel, in tal periglio” (Maometto II), where she wields perfect breath control as well as a magnificent legato. The Willow song from Otello is sung with intensity and pathos. All the other arias, without going into details, show the same command of the bel canto technique and sense of style.

My only regret is the exclusion of Ermione’s final scene: judging by the ferocity shown in Armida, Ms. DiDonato would be a perfect scorned Greek princess.

Edoardo Müller seems to share the mezzo-soprano’s intentions and conducts the Orchestra e Coro dell’Accademia di Santa Cecilia with gusto and fearlessness, always careful not to overwhelm the soloist’s voice. Tenor Lawrence Brownlee makes a pleasant cameo appearance in the “Otello” excerpt singing the Gondolier’s sorrowful Dantesque phrase.

This recording is an unqualified success.

Comments