Evidently, no one had told the Paris Philharmonie about the opera’s hour-long prelude, because, an hour before the performance, the doors to the venue were still closed and hundreds of spectators were queued-up outside waiting for the musical “greeting” to begin.

When we were eventually let in, many spectators (including myself) went in search of the location where the prelude was playing.

A few confusing conversations with security staff and a wild goose chase around the theater later and I discovered that the opera’s prelude was being broadcast in a small section of the foyer.

When I arrived at that section, I heard the quietest hum of music emanating from a few tin-pot speakers, more or less drowned out by the general hubbub of chatty spectators.

Finding no seating near the main hub of speakers, I decided to sit cross-legged on the floor and let the sound wash over me as best I could. I reckoned that Stockhausen—who remained a hippie long after it was cool—would’ve approved.

The staff were less understanding, and I was soon picked up off the tiling by a duo of burly security guards and placed on a chair on the periphery of the central speaker conglomeration.

By that time, I rather gave up on trying to hear Stockhausen’s electronic prelude and decided to take my seat for the opera-proper.

However, the hour’s worth of pre-show entertainment made the audience rather late getting to their seats, despite arriving at the theater an hour earlier than usual. There were still queues to enter the hall at the opera’s slated start time, delaying the entire performance by 20 minutes.

There was due to be another hour or so of “farewell” music in the foyer after the opera. But given that the performance didn’t end until after 11:00 pm, it seems that this element of the performance seemed to have been scrapped: presumably to let the ushers get home in a timely manner.

The pandemonium that greeted me on Monday night perfectly encapsulates one of the central facets of Stockhausen’s Licht: It’s a logistical nightmare.

Indeed, I got the distinct sense that the opera’s bizarre set of requirements had pushed the Philharmonie to its organizational limit.

Stockhausen’s vision with the “greeting” and “farewell” music was that the audience essentially heard the opera twice. The opera is accompanied by a two-hour long electronic backing track which plays nonstop throughout the action.

The “greeting” and “farewell” music consists of this backing track, divided in two, and played on its own. It’s mostly long, hypnotic droning harmonies with a few ambient sounds thrown in. Hearing it on its own is almost like stripping back the opera’s layers of topsoil and admiring its glistening bedrock underneath.

Sadly, the challenge of having the audience hear the opera’s music twice—in two different spaces, with two different sound systems of equal quality, all in one evening—proved too challenging for the Philharmonie, and Stockhausen’s prelude became so much background noise.

Freitag is the fifth opera in Stockhausen’s epic Licht cycle.

Composed between 1977 and 2003, Licht consumed much of Stockhausen’s later life. There are seven operas in total, one for each day of the week (although Stockhausen didn’t write them in weekday order—he proceeded Thursday, Saturday, Monday, Tuesday, Friday, Wednesday, then Sunday)—a total of 29 hours of music.

Stockhausen did not live to see the premieres of all the Licht operas (Wednesday and Sunday, perhaps the two most ambitious works in the cycle, were not performed until after his death).

And it is an impressive work. When I was in college, I was absolutely fascinated by the scale and ambition of this work, entranced by the sheer megalomania of Stockhausen’s vision. I wrote my honors thesis on the interplay between formalism and materialism in the cycle. The fact that I had never seen (and likely never would see) the full cycle only fueled my curiosity.

Stockhausen based his cycle on an obscure piece of occult literature called the Urantia Book. Supposedly transmitted to its author, William S. Sadler by an extraterrestrial in Chicago during the Great Depression, the Urantia Book is broadly a retelling of the Bible in which all the supernatural figures are aliens.

God, his angels—even Jesus—are all creatures from outer space who rule over a series of super-universes. Heaven (here a celestial body known as The Isle of Paradise) sits in the center of everything and is surrounded by a ring of utopian galaxies called Havona. Earth (now named Urantia) sits in the far-off Nebadon local universe of the Orvonton superuniverse. Mixing Adventist religion and science fiction, the book is an important precursor to religious movements like Scientology.

Sadler, the Urantia Book’s author was a lifelong right-wing grifter. Although he had trained in psychiatry under Sigmund Freud, Sadler’s most profound influence came from the Kellogg brothers, wealthy cereal entrepreneurs.

Through the Kelloggs, Sadler became interested in eugenics and population control. He began his writing career penning a series of vile eugenicist tracts with titles like Race Decadence, which argued in favor of “Nordic” supremacy and against miscegenation.

Prior to the Urantia Book, Sadler dabbled in all manner of kookiness, promoting all manner of alternative medicine to anyone with the money to buy in. The Urantia Book, however, was by far his longest scam—a decades-long attempt to start an alien religion.

As bizarre as the Urantia Book might sound, Sadler was a wholly unoriginal writer: those parts of the Urantia Book that are not directly plagiarized are just a generic mishmash of pop cosmology and run-of-the-mill occultism.

Notably, Sadler copied many of his early eugenicist theories directly into the Urantia Book. The book openly ranks various human races based on superiority, suggesting that genetic defects in the so-called “inferior” races were the origins of physical ailments, psychological afflictions, and social unrest (the book, for example, argues that childbirth was not painful prior to racial miscegenation.)

The Urantia Book suggests that there is an existential imperative, laid down by God, to eliminate “inferior” races in order to restore order in the cosmos: “Unrestrained multiplication of inferiors, with decreasing reproduction of superiors, is unfailingly suicidal of cultural civilization.”

In the Urantia Book, Adam and Eva are aliens who arrived on earth to promote “race betterment” on Earth by populating the planet with genetically superior beings. They are the mother and father of a white-skinned, blond-haired, blue-eyed race on earth.

The Fall, in the Urantia Book, occurs when Eva, in an attempt to speed up God’s eugenicist plan, procreates with Cano, a member of the “inferior” Nodite race. This prompts a brutal race war between the “superior” children of Adam and Eva and the “inferior” Nodites (Sadler believed that civil disorder was the direct consequence of miscegenation). God then punishes Adam and Eva for straying from His divine orders by rendering them mortal.

Stockhausen’s Freitag aus Licht takes the Urantia Book’s story of the Fall as its plot. In the opera, Eva (Eve) is convinced by Ludon (Stockhausen’s name for Lucifer in this opera) into copulating with Kaino, resulting in a disastrous race war—stopped only after Eva repents her “transgression.”

In Freitag, Stockhausen takes Sadler’s eugenicist ideas and runs with them. The opera calls for two large groups of child musicians who are divided along racial lines: the Black children of Ludon (played in blackface in the original production) and the white children of Eva.

The white children play orchestral instruments and fight with modern weaponry; the Black children play African percussion instruments and fight with spears and arrows.

And Stockhausen goes out of his way to let his audience know that these two races should not mix. In the libretto (by the composer himself) Eva and her white children are associated with light while Ludon and his Black children are associated with darkness.

And when Eva mates with Ludon’s Black son, Kaino, she produces a nefarious “bright darkness” or a “day-night” while the voice of Stockhausen himself booms over the loudspeaker, reprimanding Eva for her act of miscegenation (“Eva! Unsere Kinder!”).

Indeed, in Freitag aus Licht, as in the Urantia Book, temptation and sin have distinctly Black origins: the original sin is embodied by the unseen figure of “Afrodite” (a crude play on the words “African” and “Aphrodite”), evoked by Ludon to convince Eva to take his Black son as her lover.

Sexuality in Freitag is thus distinctly racialized: Stockhausen doesn’t care so much about the sex act itself but about the race of the participants and the genetic status of their children. The morality of sex, then, broadly corresponds to eugenicist goals: “good” sex is tied to the reproduction of the white race, while “bad” sex is associated with the “tainting” of white bloodlines with Black genes.

As if the opera’s plot wasn’t disturbing enough, Stockhausen inserts a series of short pantomimes in between each scene of the opera, ostensibly intended as a crude warning against miscegenation.

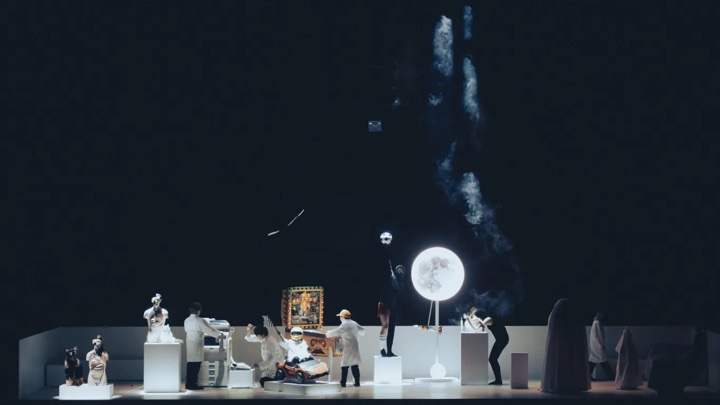

These pantomimes consist of twelve “couples,” who are revealed one by one over the first two thirds of the opera: man and woman, cat and dog, photocopier and typewriter, racing car and racing car driver, pinball machine and pinball machine player, soccer ball and foot, moon and rocket, ice cream cone and tongue, arm and syringe, pencil and pencil sharpener, violin and bow, and crow and nest.

Each “couple” has its own distinct physical movement that they perform, accompanied by a unique electronic sound that plays when they are in motion (for example, the sounds that accompany the cat and dog are various woofs and meows).

After Eva sleeps with Kaino, the “couples” start swapping partners creating new “unnatural” pairings (the man, for example, ends up with the cat, the woman with the dog, the moon with the syringe, the raven with the violin, etc.). And as “couples” begin to intermingle, the electronic music that accompanies them is also transformed as the sounds associated with each couple are reconfigured in new ways (for example, the sounds of a woman singing become mixed with the sounds of a cat barking as soon as the dog starts mating with the woman).

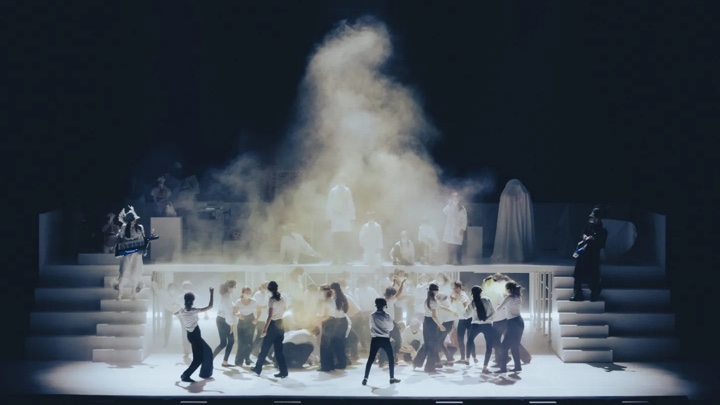

These new pairings produce a series of bizarre “hybrid” offspring (a woman with a dog’s head, a pinball machine with a leg, a cello with a raven’s head, a rocket with an arm, a pencil with a mouth, etc.). At the end of the opera, this “mutant” progeny forms a choir and repents for the sexual sins of the “unnatural” couples that produced them. The opera ends with these hybrid creatures being euthanized in a giant fire.

These pantomime “couples,” in the context of the opera, appear as a gross metaphor for Stockhausen’s regressive attitudes on interracial coupling. He compares the white Eva copulating with the Black Kaino to a woman having sex with a cat or a violin bow mating with a bird’s nest. Not only that, but he implies that any offspring from such “unnatural” unions are inherently sinful and should be destroyed.

It’s an absolutely horrific message, delivered with casual puerility. The sheer immaturity of these pantomime sequences belies a disquieting white supremacist attitude towards sex. The opera, then, reads like an alarming modernist endorsement of Sadler’s eugenicist ideology, an absurdist amplification of his disgusting racial views.

Stockhausen’s mentally ill mother, Gertrud Stockhausen, was gassed to death in 1941 as part of a Nazi euthanasia program (he dramatizes her death as part of Donnerstag aus Licht). His father, Simon Stockhausen, was killed in action in 1945 fighting for the Nazis. Karlheinz himself served as a Nazi stretcher-bearer during the war.

Whether it was Stockhausen’s Nazi past that led to his fucked-up views on race (as some have speculated) or whether his white supremacy developed later in life, it’s hard to say.

But one thing is clear: Freitag presents a message of racial extermination masked only by the sheer bizarreness of Stockhausen’s theatrical vision.

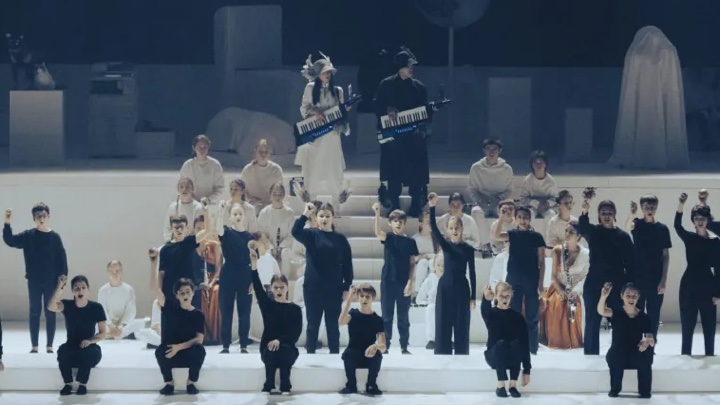

In some respects, director Silvia Costa did a fair job of minimizing the ugly eugenicist elements of Stockhausen’s opera.

Instead of presenting the two children’s ensembles as separate (warring) races, Costa simply dressed them in different colored outfits.

She also stripped away much of the racist stereotypes that characterized the opera’s first production: while Stockhausen originally intended the Black characters to be more “primitive” in appearance than the white characters, Costa opted for a clean, minimalist aesthetic across the board.

She also reconceived the pantomime elements of the opera—seemingly intended to display an anti-miscegenation message—as a series of classroom science experiments. The various pantomime “couples” (which, in this production were represented through a mixture of dance and animatronics) were created and manipulated by a group of young children in lab coats.

This had the effect of softening the fascistic message of these passages: the manipulation of these “couples” felt more like a kid’s pair-matching game than a visual metaphor for the opera’s eugenicist message.

But the eugenicist message was still there. And I personally felt that this new production didn’t go far enough in countering the racist messaging of Stockhausen’s opera—in part because it remained all too true to Stockhausen’s original vision.

In fact, I felt that the neat, paired-down production design—while avoiding some of the more openly racist aspects of Stockhausen’s piece—merely made the opera’s message all the more insidious.

In many ways, Costa merely gave the eugenicist elements of the work a trendy new makeover: all the most disturbing features of the work were still there, but they were dressed now in chic, minimalist attire.

It is easy to see why an aesthetic of clinical abstraction is appealing to modern directors: it allows a degree of distance from the work’s content. But ultimately, this pristine, monochrome production does little to address or Evan counter the dark implications of the drama.

An ideal production of Freitag aus Licht would not be afraid to actively undermine the ideologies that underpin Stockhausen’s aesthetic vision. It would not shy away from denouncing and Evan ridiculing the composer and his nauseating beliefs. It would acknowledge and actively decry the opera’s racism while transforming its message from one of oppression and violence to one of liberation, diversity, and equality.

In other words, an ideal production would not (and should not) be truthful to the composer’s dramatic intentions—for when the composer’s intentions are vile, we have a moral obligation to leave them behind. It would, instead, take any and all license needed to reimagine or rewrite the work, to excise or recast its most disgusting elements.

Sadly, until Stockhausen’s works enter public domain, I doubt this would be possible. One gets the sense that Kathinka Pasveer and Suzanne Stephens (two woodwind virtuosi who formed a romantic polycule with the composer in his later years) still exercise a large degree of control over the Stockhausen Estate.

This is partially by the composer’s own design. Wanting complete control over his music, Stockhausen broke with Universal around the time that he started Licht, taking complete responsibility for the publishing, recording, and distribution of his own works. He also set up a series of Darmstadt-style summer courses near his home in Kürten, designed to train musicians to perform Stockhausen’s works in the way that the composer intended them.

The extreme control that the Stockhausen Estate exerts over his musical legacy has, however, helped to safeguard the quality of contemporary performances of his works.

Indeed, for all that I found myself revolted by the opera itself, I couldn’t help but be dazzled by the high caliber of the performance itself.

Stockhausen’s music is fiendishly difficult. The vocal writing is extraordinarily virtuosic—calling for an extreme range of extended techniques—and is mostly accompanied by long, dissonant electronic drones.

The musical material itself is serial (albeit not dodecaphonic), based on three overlapping tone rows which correspond to the cycle’s main characters and which are segmented into seven chunks corresponding to the seven days of the cycle. (Freitag, I should add, mainly uses the tone rows associated with Eve and Lucifer: the third protagonist, the archangel Michael, does not appear in this day of the cycle).

These tone rows (which Stockhausen calls the “super-formula”) not only include pitches, but also rhythms, dynamics, and timbres, such that almost every musical decision that Stockhausen makes in the cycle can be traced back to an element of the “super-formula.”

While these serial constructions can begin to sound somewhat melodic after they’ve been repeated over a three-hour opera, they also pose unique difficulties to the singers: the score is meticulously notated, in accordance with Stockhausen’s serial plan. Its singers must memorize an incredible amount of musical detail—all within an atonal idiom unlike any other.

As a result, every role in Freitag is a tour de force. But the opera’s true stars are the hundred or so children who perform a large bulk of the opera’s (endlessly challenging) music.

The Children’s Orchestra of the Conservatoire à Rayonnement Régional de Lille, who played Eva’s orchestra of white children, and the Choir of the Maîtrise Notre-Dame de Paris, who played Ludon’s chorus of Black children (and also depicted the race war that follows Eva’s fall) made Stockhausen’s score sound almost easy (it’s not!).

Both ensembles performed with machine-like precision (well coached by music director Maxime Pascal): there was not a single note out of tune, not a single late entry (this is a particularly challenge for the children’s choir, who must sing while playing percussion instruments). Collectively, they produced a lovely sound, maintaining a pleasant textural and timbral balance throughout.

I appreciated the utter musical and dramatic commitment demonstrated by these young musicians. Stockhausen—ever the control freak—goes so far as to notate the physical movements of both singers and instrumentalists (yes, even the orchestra gets choreography!). The children truly took ownership of this gestural language, rendering this eccentric dance with great aplomb.

Stockhausen also calls for 24 child soloists who periodically interrupt one of the large choral scenes with hooting, screaming, squawking, and hollering. I must give a special shout-out to these soloists, who rendered the paroxysmal, glossolalic (and downright nonsensical) solo interjections with confidence and flair.

Jenny Daviet delivered an exquisite performance in the gargantuan role of Eva. So much of the time, Stockhausen’s protagonists appear more like religious symbols than fully fledged characters. As a result, Eva comes off as a rather static role: she spends much of the opera standing about and gesturing ritualistically or slowly processing across the stage.

Daviet did a marvelous job of bringing a certain operatic-ness to her character, adding emotion and drama to a role that can often seem rather cold.

I particularly appreciated the warmth and vulnerability with which Daviet approached Stockhausen’s tortuous vocal lines: she endowed his unorthodox vocal effects and gnostic word games with a degree of humanity, finding new moments of drama in the obtuse, fragmented libretto.

Antoin Herrera-López Kessel gave a sympathetic interpretation of the villainous Ludon/Lucifer: his rich-voiced dignitas brought a touch of class to one of Stockhausen’s more distasteful roles.

Ludon’s music requires an enormous range, and Stockhausen often calls on his singer to traverse from the very bottom to the very top of his range (Lucifer’s strand of the “super-formula” is full of ascending major sevenths). Kessel found gorgeous colors within this vast tessitura: a marbly strohbass, a light, fluttering head voice, and a commanding voix mixte.

The role of Kaino is a rather thankless one: he has nothing much to do until the second act, where he performs a very long, slow sex scene with Eva—a blunt plot device that rather distracts from the singing.

Halidou Nombre’s clear, tender delivery transcended the crassness of Kaino’s material. He found elegance and lyricism in the angular serial constructions that pervade the score, ultimately lending his coital interlude a feeling of genuine intimacy.

In Licht, the instrumentalists are just as much a part of the drama as the singers. Various characters in the opera are played by instrumentalists, who are given physical choreography (and sometimes sung or spoken dialogue) to match their musical lines. These instrumentalists appear onstage, in full costume, music memorized, and interact with the singers as part of the drama.

Freitag’s instrumentalist-characters include Elu (basset horn) and Lufa (flute)—Eva’s handmaidens—and Synthibird, a Papageno-like figure who plays the synthesizer.

These roles were rendered admirably by Charlotte Bletton and Iris Zerdoud (Lufa and Elu), and Sarah Kim and Haga Ratovo (sharing the role of Synthibird).

Sadly, it was often difficult to distinguish the synthesizer playing from the 8-track electronic music that underscores the entire opera, especially when both are mixed through the same sound system (this is a design flaw in Stockhausen’s score more than anything else!). However, I greatly enjoyed the virtuosic woodwind passages—playfully delivered by Bletton and Zerdoud—which overlap much of the vocal music.

There was something bittersweet about seeing such an incredible performance lavished on such a problematic work—impressive musical forces amassed in service of such a violent operatic vision.

I found myself thoroughly enjoying the music, which, in my opinion, is some of Stockhausen’s best. It has a hypnotic allure, especially when performed well. The spatialized electronic drones, the recurring serial motifs, and the long, slow unfolding of the opera’s formalist design all make for entrancing viewing.

But I ultimately left the theater feeling rather dirty—as if I’d just walked out of a Trump rally or QAnon convention. No amount of musical prowess could mask the opera’s fascist messaging.

And thinking on the state of the world today, where the eugenicist theories touted in Licht too often enter the mainstream, I couldn’t help but feel that it is reckless to resurrect a work like Freitag as it was written. We have a moral responsibility to leave Stockhausen’s racism in the past, to ensure that we don’t inadvertently parrot his views.

Cornelius Cardew, Stockhausen’s one-time student turned Marxist avant-gardist, once decried his former mentor’s music as “a part of the cultural superstructure of the largest-scale system of human oppression and exploitation the world has ever known: imperialism.”

Cardew (an extremely dogmatic figure) argued that Stockhausen’s works cultivate an air of peace-and-love mysticism to hide their imbrication in the most violent tendencies of bourgeois culture.

Certainly, in the case of Freitag, critics and musicologists have long neglected to address the disquieting aspects of this work, often beguiled and bamboozled by the ambition, the absurdity, and the spirituality of Stockhausen’s cycle.

But behind all the megalomaniacal spectacle of Licht was an ageing racist attempting to reconcile his innate conservatism with his reputation as a modernist enfant terrible. The aliens and angels, the sanctity and science fiction of Licht are a smokescreen for a vile man’s eugenicist fantasies.

Comments