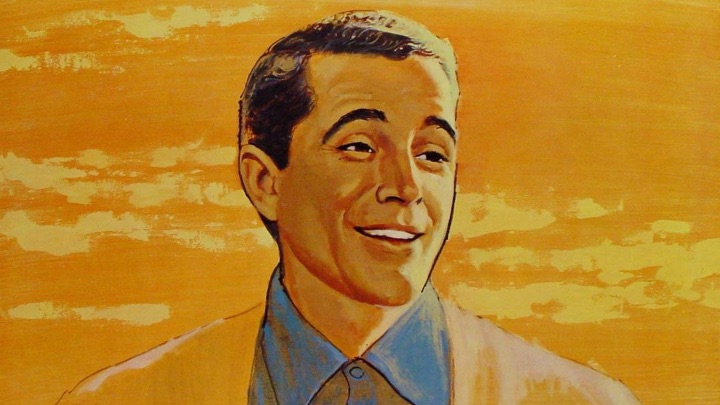

Turns out, I was nowhere near “comprehensive enough” in offering the full measure of Como’s versatility. The irony is, this postscript installment is perhaps more fitting for this reader audience—aficionados of opera and classical singing—than the first was.

In the expression of the “new small talk,” I was initially “done in” by my own dismissive, preconceived notions. You might call them “prejudices.”

Which are?

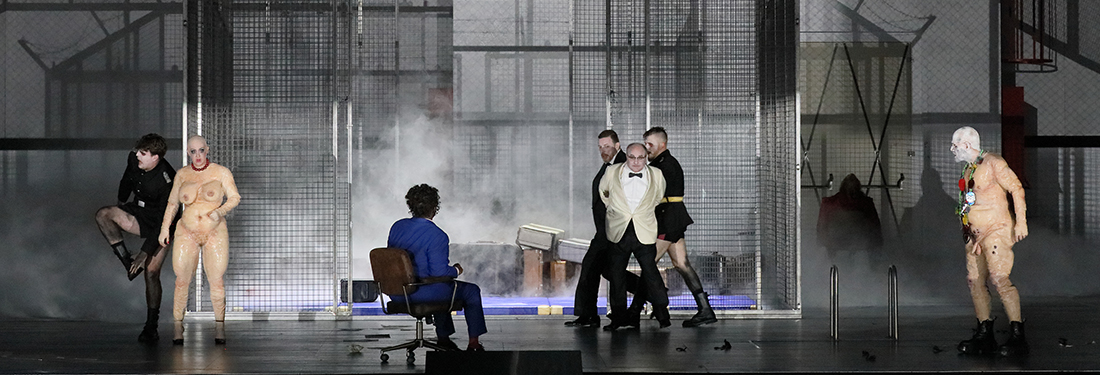

I have a serious aversion to a whopping number of what they call “crossover” excursions: pop singers doing classical material, and classical singers doing pop material. Not enough of a voice or technique in the former case, and too much voice (along with the overly-covered vowels) and obtrusive operatic manifestations in the latter. In many junctures, the switcheroo rarely ever sounds right, let alone credible and believable in either instance; the slumming schtickery is the most prominent factor. In many cases, just plain bad taste, and an ill-at-ease clumsiness prevails.

Even more apprehension often occurs when either (mainly current) pop or opera singers undertake Christmas or similarly traditional sacred or hymnal pieces. As we’ve heard for ages now, many of these ponderous executions (you can infer multiple usages here) are often downright embarrassing: they’re laden with kitschy, schlocky arrangements (Como’s “team” were occasionally guilty of this), and vocally, the self-conscious approach descends to smarmy, oh-so-precious over-emoting and mugging-tugging of the melodic line.

Some months ago I ordered a bargain-priced 10-CD set, originating from Germany, of Como’s first 20 LP releases, to play in my car. I at first artfully dodged the Christmas songs, the sacred albums I Believe, and When You Come To The End Of The Day. From the titles alone they all seemed like the kind of bygone albums that always get dumped at flea markets and thrift shops but which never get purchased, and wind up being landfill offal.

Nevertheless, after a fashion, I happened to glance at the *I Believe* album contents. Mostly of them familiar traditionals: “I Believe,” “Onward Christian Soldiers” (the Sullivan tune, with rather dubious lyrics), “Goodnight, Sweet Jesus,” “The Rosary,” “Nearer, My God, To Thee,” Abide With Me,” “The Lord’s Prayer, “Bless This House,” and a couple of items I’d never heard that Como sang: the Yiddish “Eli, Eli,” and the Hebrew-Aramaic “Kol Nidrei.”

Also included is the Schubert setting of “Ave Maria” and decided to try it out: it is a straight-up classical piece. I was pleasantly, genuinely surprised at the result. But then again, not; it’s Como, after all.

How often is it that you get to offer the claim—the impossible dream, really—of “impeccably flawless” in singing? What’s more, astonishingly, this sounds almost too easy for Como; there’s not so much as a whisper of effort or even the barest insecurity on his part anywhere—no audible intake of breath, or discomfort at the end phrases. The line is handled with suave, fluid élan, with exquisite portamenti and graceful shading; the breath output is wedded to the tonal and textual expression of the seamless, flowing phrasing:

To give an idea of how ahead of his contemporaries Como was in this sort of material, here is Frank Sinatra doing the same piece; he sounds tentative and not wholly at ease:

My initial reluctance to hear this album has turned over to frequent listening of it. Many of these pieces are melodically beautiful, and they sound it when done as attractively as Como does them. An absolutely straightforward approach, coupled with absolute sincerity, and handled with masterful vocalism, you realize just what the ideal is in terms of how they are presented.

The piece that really pinned my ears back, though, is the Catholic confessional, “Act of Contrition,” here set to music by Joseph Leahy.

If I did not know that this was Perry Como singing, I would have assumed it to be a young, classically-trained baritone. In the middle section he does the arc of the rising, soaring line with stunning, almost operatic power and ease, with the kind of authority you would hear in a well-trained classical singer. In addition, he intones the text with great feeling and sensitivity. It is fervent and moving, even if you don’t agree with its sentiments:

In “Bless This House” Como coasts along the line serenely, until he suddenly pulls out a splendidly operatic finish:

This totally unexpected showing of this capability brings up a viable question. That Como was so easily able to summon up this hallmark caliber of vocal means and rising easily to the challenge makes one wonder at the training he received. All of his colleagues and collaborators have asserted that Como never had a singing teacher, not took a single lesson.

Even more confounding, his major collaborators have stated that Como never even warmed up before performances. It seems very likely that he just learned what he could do with his voice somewhere along the way, and applied it as he felt it to be appropriate.

Though he was known as a “crooner,” the kind of singing he does here, with a full-bodied, supported tone—it can’t be faked. The question remains, then, if he could be heard, unmiked, in this material in a large venue. I think yes; the giveaway is in the unmistakable resonance in the tonal production: the sound has a blooming, “sound-box” vibrancy you don’t hear in most pop singers.

Coming tomorrow: We’ll hear how Como was able to “assume” different vocal identities.

Comments