Ullmann collaborated with librettist Peter Kein in 1943 while being held at the Nazi concentration camp of Theresienstadt (Terezín). The opera was even being rehearsed the year after, until the Nazis recognized it to be a satire on Adolf Hitler (as the title role). Subsequently, both Ullmann and Kein were sent to Auschwitz concentration camp and died there.

The fact that the score survived was nothing short of a miracle. Musicologist Michael Graubart in his 2009 The Musical Times article titled “The emperor of Atlantis: the first British production” detailed this journey: Ullmann entrusted the manuscripts to Dr. Emil Utiz, who then passed them to Dr. Hans G. Adler, both Terezín survivors. It was Adler’s close relative, Kerry Woodward, who prepared the first performing edition and conducted the world premiere with Dutch National Opera in Amsterdam on December 16, 1975, 32 years after its creation.

Since then, performances of Der Kaiser von Atlantis had spread like wildfire, particularly in the last two decades. I personally saw a production at Teatro Real in 2016 in Gustavo Tambascio’s macabre staging. My most favorite video (prior to this performance) was from last year Wolf Trap Opera’s mounting, in a Richard Gammon’s Cabaret-inspired take. (The personification of the Loudspeaker as the Emcee from Cabaret was a pure stroke of genius!)

You might ask what caused the rise of such an unknown chamber opera. I think the conductor James Conlon, in his 2003 interview with the New York Times described it best in the following two paragraphs:

Mr. Conlon says he sees the opera as at once a political satire and a parable of hope ”when there is no longer any reason to hope.” The Emperor, living in total isolation, represents Hitler; his ally, the Drummer, who sings a menacing minor-key version of ”Deutschland Über Alles,” is Eva Braun. The plaintively romantic Harlequin and a pair of Romeo and Juliet-style lovers represent the lost world of normal human emotion.

The Emperor’s change of heart is, for Mr. Conlon, a wish-fulfillment not too far removed from events today. The wistful cabaret-style music here becomes heavier yet more radiant. The Emperor’s closing aria echoes Brahms and Mahler. The lovers, Harlequin and even the Drummer and the Loudspeaker, welcome death with a sublime setting of Luther’s chorale melody ”A Mighty Fortress Is Our God,” to the words ”Thou shalt not use the name of Death in vain, now and forever.”

It was no wonder that Der Kaiser von Atlantis was the piece chosen by Atlanta Opera as part of their Big Tent Series during the Covid-19 pandemic. In the video announcing them, Atlanta Opera’s Carl W. Knobloch, Jr. General & Artistic Director Tomer Zvulun, who also acted as the director of this production, admitted that Der Kaiser von Atlantis was “very meaningful to him personally” and it was reflected in the sensitive way he imagined this allegory tale.

Presenting operas in time of Covid-19 pandemic was certainly not an easy task. Pretty much all US opera houses chose to go dark since March 2020, while select few resolved to present online content of past productions, most notably the Metropolitan Opera. Across the pond, European opera houses were more creative in terms of finding way to do it while still within the boundary of what was allowed by their respective governments. Two examples were the most significant; Deutsche Oper staged Jonathan Dove’s distilled arrangement of Das Rheingold at their parking deck last June, and Teatro Real mounted social-distancing La Traviata to social-distancing crowd (yes, indoors) as early as last July!

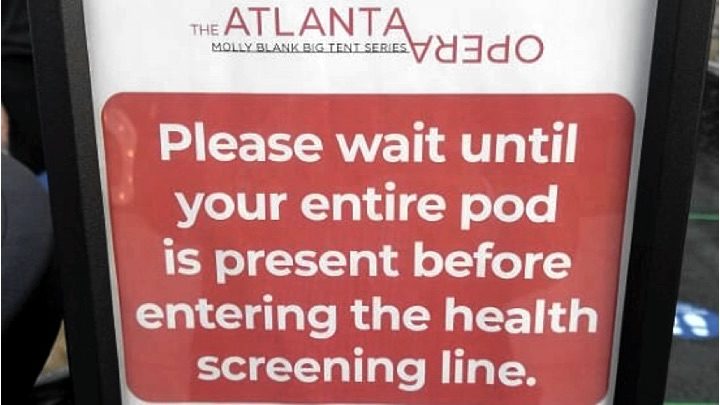

Atlanta Opera has to be applauded for rising to the occasion and staging arguably the most innovative idea of them all, performing Der Kaiser von Atlantis (and Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci) outdoors in a circus tent! Their website announced that “This outdoor experience was designed in consultation with leading experts in the fields of epidemiology, public health, workplace/industrial hygiene, and infectious diseases” and they took the safety issues extremely seriously!

For these performances, the tickets were sold as social-distancing “pods”, accommodating up to 4 people in one party. You can see the online seat map and its realization (as one of the pods directly in front of the stage) in the pictures below. Personally, I was expecting a somewhat enclosed “pods” based on the seat map, but I recognized that it would make even more complicated logistically and potentially poorer sightlines as well.

The safety precautions started even before the audience entered the space. Ushers directed complete parties through a health screening line, where each person filled out a health screening questionnaire at their own smart devices, including details for contact tracing. At the screening booth, temperature check was conducted (they wouldn’t allow anyone with temperature beyond 100.4° F) and audience was invited to sample hand sanitizers before being led to their pods. At no time did the audience feel unsafe, in my opinion!

What truly warmed my heart was despite all these rules and restrictions, there was a heightened sense of excitement and welcoming among every single Atlanta Opera staff member; from the ushers, health officers, crews, all the way to Zvulun himself! Their enthusiasms were genuine and palpable, and in turn it helped to put audience’s minds at peace, even bringing a sense of anticipation of great thing to come!

The health and safety considerations were not just limited to the audience but also extended to the whole cast and musicians as well. Prior to the show, they presented a video by Dr. Carlos Del Rio from Emory University School of Medicine highlighting the drastic steps that they took to ensure the safety of all the performers. Those included putting the orchestra in a separate tent behind the stage (a move similar to what Opernhaus Zürich did when they premiered Boris Godunov last month), ensuring all performers to sing with masks while they interacted with each other, and placing isolated chambers on stage when a singer could sing unmasked inside. I feel that all those were necessary and imperative precautions, especially in light of news around Bolshoi’s recent performance of Don Carlo!

With all those constraints imposed on the staging, it was a little miracle on its own that Zvulun and his creative team were able to coax the interpretation into a coherent, even beautiful reading that was faithful to the score.

Julia Noulin-Merat’s set can be seen in the above picture. At the center, decorated with thousands of shoes (I will discuss the importance of it shortly), was the main stage, the domain of Death. Two almost identical diorama-like isolated chamber placed on both sides of it, simply decorated with a chair and a telephone. The stage left would be Kaiser Overall’s “castle”, while the other one belonged to The Drummer. Two other smaller chambers placed behind the main stage – plain and unadorned – the one on (stage) right would be the Loudspeaker’s “phone booth” and the last one would be occupied by the Girl.

When I first heard that a circus tent would be used for both Pagliacci and Kaiser von Atlantis, I was rather skeptical about how it would translate, particularly for Kaiser. However, Zvulun completely blew my mind by having Kaiser performed by a circus troupe! It was a performance that both harked back to the time when the opera was written (Terezín was known for having rich culture life, and Ullmann’s score included many instrumentals for dances) and looked forward to modern times (a circus troupe in time of pandemic or political crises, for example)! In the following video, Zvulun himself authoritatively detailed his interpretative take on Kaiser (and Pagliacci):

The seemingly simple stage stored many hidden surprises, particularly with regards to those shoes. In the final act, Death resumed his duty “roots up wilting weeds, life’s worn-out fellows” by the act of removing shoes and stashing them in his domain, turning it into a sort of pièce de résistance.

In addition, while initially I felt the circus acts during the Präludium were pretty superfluous, their subsequent usages in the Intermezzi to project the decay of the society – by way of broken movements and clever uses of masks – were super effective and heartbreaking. Props were used sparingly but efficiently, following the libretto. I loved the fact that the leitmotif “Hallo, hallo” and the preceding (or foreboding) Trumpet melody were mostly staged as phone calls between the Loudspeaker and Kaiser Overall while he updated him of the bad news!

Even the limitation imposed by the isolation chamber was fully realized to depict Kaiser Overall’s state of mind. He spent most of the opera trapped in the stage left diorama, and he visibly grew more and more desperate as he heard bad news from the Loudspeaker – it reminded me of the much-parodied scene from the German movie Downfall.

Joanna Schmink’s costumes complemented the eclectic set with striking use of bold colors for both the singers and the circus performers. Schmink dressed both Kaiser and the Drummer in navy blue, as if to emphasis what Conlon mentioned in the quote above. In the final aria, Kaiser removed his jacket to reveal a white undershirt, matching the color for Death. Interestingly, the Girl was sporting typical Harlequin colorful costumes, while Harlequin himself perused earthy green and brown color scheme.

The Loudspeaker’s maroon getup and the Soldier’s grey military outfit with navy blue sash completed the ensemble. All of them wore masks in similar color palette, with notable exception of Death, whose mask indicated the terror of his role! Last but not least, Ben Rawson’s multiple neon lights illuminated the action and gave the area an other-worldly feel to the whole proceeding. You can see a sneak preview of the production below.

Musically, the performance was also commendable, with a few caveats. As mentioned above, as part of the safety procedure, the orchestra and the conductor were housed at a different tent behind the stage (while maintaining social-distancing protocol), and the orchestral sound were transferred through loudspeakers in the main tent. This setup, however, inevitably led to the feeling that the singers performed to backing tracks instead of live accompaniment. On that opening night, the orchestra and the singers worked like a well-oiled machine, without any visible synchronization problems, definitely due to considerable amount of rehearsals to achieve such perfection!

Maestro Clinton Smith led a lyrical reading of the score, emphasizing the many almost solo-like passages in the chamber opera. This was actually one of the greatest aspects of the performance, in my opinion. In a lot of past staging inside great opera houses (including the one I heard at Teatro Real), the orchestra was beefed up in order to be heard at the back, and as the result the exquisite intricacy of the score, where individual instruments danced around vocal lines, oftentimes got lost along the way.

I felt that I reached a new appreciation of Ullmann’s score in this fashion. For example, while Ullmann had always been recognized as contemporary to Weill and Hindemith, I heard echoes of his mentor, Alexander von Zemlinsky – particularly of his 1922 Lyrische Symphonie – in the Devil’s aria “Ich bin der Tod”. There was no mention of particular edition being used for this production, so I assumed they were using Ullmann’s original instrumentation (also the subject of Graubart’s article above).

Kaiser von Atlantis was a true ensemble work rather than a star-driven vehicle. In that aspect, the all-American cast that Atlanta Opera assembled collectively excelled, with nary a weak link among them. It had to be said at the outset that, due to the staging and all the restrictions, all of the singers were amplified, and that some of the voices could sound rather muffled when the singers wore masks. However, they all worked extremely hard and managed to put their individual spins on their characters.

No stranger to contemporary operas, baritone Michael Mayes showed considerable acting chops as the title role and projected kaleidoscopic colors in his voice, from manic arrogance in the beginning to delicate sensitive phrasings of his farewell aria “Von allem, was geschieht”. That last aria was particularly memorable, as there were many different opinions on whether or not Kaiser Overall was redeemed at the end, and in Mayes’ interpretation, Kaiser Overall clearly recognized his sins and repented!

The Drummer transformed mezzo Daniela Mack into a dominatrix, complete with a whip. She sounded a little tentative in the beginning that night, but she quickly recovered and presented a wholesome view of the villainess of the opera. Her voice sounded round and full, and she clearly had a great time playing the role.

The veteran bass Kevin Burdette offered an interestingly different characterization of Death, as he imbued, both with his voice and his acting, the role with a deep sense of world-weariness, including when he declared on strike and broke his sabre. It was a refreshing reinterpretation of the role, completely appropriate in Zvulun’s concept, and, frankly, a somber reminder of what Death had been in 2020 so far! Similarly, Alex Shrader’s Harlequin was full of sadness and gloom throughout, even when he was dancing! Unfortunately, I couldn’t help but noticing that Shrader suffered from being muffled the most, particularly as he was wearing the mask the whole time.

With his booming dark voice and a large black loudspeaker, Calvin Griffin made a striking (and loud) impression as the Loudspeaker (no pun intended). Tenor Brian Vu and soprano Jasmine Habersham completed the cast as the pair of the Soldier and the (Soldier) Girl. Their voices beautifully matched each other, and their duet “Schau, die Wolken” was brimming with childlike innocence reminiscent of the Evening Prayer from Engelbert Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel. In the next video you can see the interaction of the cast at the backstage.

In summary, was this an ideal production? The answer was probably “No”. But, this performance truly resonated with me, and I would cherish it for as long as I live. Zvulun in his introduction called this “the pandemic opera” and I couldn’t agree more with him, for this represented a miracle of miracles – a sensitive reading of a highly relevant chamber opera, performed by an extremely motivated group of performers, supported by highly dedicated staff and crews, and adhere to highest level of health and safety precautions – what else would one hope from an opera experience?

Thank you Atlanta Opera for showing the resoluteness and strong resilience during this difficult time. The purpose of Art – and Opera in particular – is to entertain, to console, to heal, and eventually, to teach, and you had shown us all of those in great abundance with this performance. May it lead the way for other US opera companies to consider alternative ways to keep the operas alive.

Header photo by Ken Howard; all other images by Michael Anthonio.

Comments