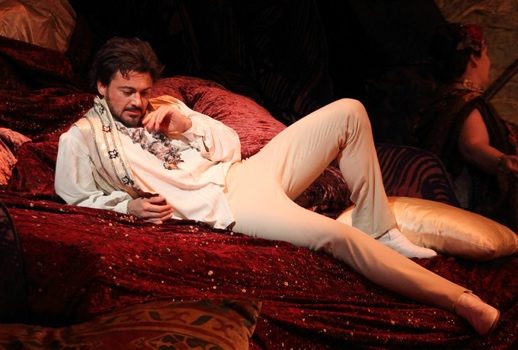

Dans les roles d’amoureux langoureux…

No amount of scholarly diligence has kept Les contes d’Hoffmann from being the messiest of all standard-repertory messes. The opera was unfinished at the time of Offenbach’s death in 1880, and in this case “unfinished” means not a deficit but a surplus of material, some added by other composers, some authentic but not unearthed and sorted out until the late 20th century.

You may not know precisely what you will hear in a new production of a much-revised problem opera such as Don Carlos or Boris Godunov, but in Hoffmann the curtain may come down on a major character dying of poison, sailing away in a gondola while laughing mockingly, or grieving over the body of a man who has been accidentally stabbed.

This is but one of many textual variations. You also may hear spoken dialogue or recitatives composed by Ernest Guiraud. One woman may play all four of Hoffmann’s love interests, or the roles may be split up. Such is the case with Hoffmann’s nemeses as well, but in modern times these are far more likely to be handled by a single baritone or bass-baritone.

“Much of what we knew about Jacques Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffmann became obsolete Friday night, when the new critical edition by Washington musicologist Michael Kaye had its first complete performance,” wrote a Washington Post reviewer on assignment in Boston in 1992. In the quarter century since, discredited editions of earlier eras have proved difficult to shake off, even in new productions.

Mr. Kaye’s scholarship has since been augmented by that of Jean-Christophe Keck. Many of us hope the joint Kaye-Keck edition will emerge as the standard, but even that edition presents alternatives, decisions that must be made. The opera remains a kaleidoscope, a Choose Your Own Adventure book for conductors, directors and singers.

The Schlesinger production’s first run was captured in a telecast that became an early opera videocassette (later a DVD), with Plácido Domingo and an assortment of the era’s luminaries as the lovers and antagonists. Thirty-five years later, one of the production’s final performances received a cinema broadcast, and so we can experience this grand old show in superior picture and sound as it goes off to its final resting place. (Trivia: The Schlesinger production both began and ended with a star tenor who at least claimed the age of 39.)

The late Mr. Schlesinger’s work, caringly revived here by Canadian stage director Daniel Dooner, combined cinematic sumptuousness with old-fashioned theatrical good sense. Wheels remained round and rolled along; sticks were rubbed together and ignited. Mr. Schlesinger and his designers (William Dudley on sets, Maria Björnson on costumes) were perceptive in the period environment they created.

Their Hoffmann moves through a world of heavy browns and grays, blacks and whites. Even Spalanzani’s party is a sober, formal occasion. Artists such as Hoffmann (and Antonia) are oppressed and stifled in this world, even when superficially encouraged. The colorfully decadent Venice of the Giulietta act—given the central placement that was dramatically indefensible even in 1980—provides the only escape.

Hoffmann has been a good role for Vittorio Grigòlo, and his portrayal does much to lift the revival out of the ordinary. He is passionate and spontaneous, and while singers around him need time to warm up, he creates the impression of having gotten out of bed warmed up, having no other setting. From his first entrance, he snaps the show into focus, and his sunny, shimmering tone and Italianate ardor hold up well over a long sing.

No tenor active today wears clothes better. Even the dissolute, stringy-haired Hoffmann of the prologue and epilogue, though rumpled, has a great tailor. Mr. Grigòlo is right at home in a production that was new when he was a toddler, for his Hoffmann is a star turn, a real divo showcase.

At the time of this writing, Mr. Grigòlo soon will return to the role in New York, having had a success with it earlier in the year in Los Angeles (reviewed here by our own Patrick Mack). If you are near the Met and missed him last time around in the Bartlett Sher production, go. You may then want the ROH performance as a keepsake.

Mr. Schlesinger’s production recalls a time before it was widely acknowledged that the Muse/Nicklausse is the second most important character in the opera. In the production’s original run, poor Claire Powell was practically on comprimaria duty. The 2016 mezzo, Kate Lindsey, is experienced in the role, but she has had better stage opportunities and more music to sing in other productions, even the Met’s flawed current one.

In the one concession to changing times, “C’est l’amour vainqueur” (the violin aria) has been added; it was not there in 1980-81. This aria, preceded by an amusing imitation of Olympia winding down (…two lovers ago), is Ms. Lindsey’s highlight. In earlier scenes, she sounds below form: muffled, distant.

Sofia Fomina‘s grapple with Olympia’s showpiece bespeaks determination more than sparkle or brilliance. The voice is small, the movement of it gluey. Better is Christine Rice‘s voluptuous Giulietta. It is a dinky role in this edition, but Ms. Rice seems liberated by the glamorous treatment of the character, and voices a potent low-woman seductress.

Best of all is Sonya Yoncheva‘s imaginative and heartfelt Antonia. There is no fragility in “Elle a fui, la tourtelle”; it is only in recitative that that quality emerges. When Antonia sings, Ms. Yoncheva suggests, an inner fire blazes up and conceals everything else as its glow sustains her. When she stops singing and must speak again, the chill of reality sets in.

Thomas Hampson cuts a fine figure and gamely submits to a lot of costume quick-changes for this production, in which the villains originally were a four-man job. Councilor Lindorf looms and gloats at stage right when Hoffmann’s affairs end in disaster, and this requires some stage deception with a Coppelius double in “Olympia.” The roles are no more vocally congenial for Mr. Hampson in London than they had been in New York. Too often he is required to scuffle in the basement of a sixtyish high baritone’s all but noiseless bottom.

Lindorf’s “Dans les rôles d’amoureux langoureux” sounds tired rather than imperious, as if the baritone is trying to prod and rouse a sluggish voice to the piece’s rhythmic specifications. The lunge to the high conclusion of “Scintille, diamant” has the quality of a desperate emergence from under water. Mr. Hampson cannot be said to be fully in the spirit of this old-time phantasmagorical production, either; he is debonair and subdued. Villainous sneers and chuckles look like impending sneezes, or possibly moustache irritation.

There is more vivacity in this score than is suggested by Maestro Evelino Pidò‘s plain, heavy reading. The most substantial act, “Antonia,” feels as hefty as an entire opera. Choral work is characterized by soggy indifference. The competitive virtues here are the performances of some aforementioned singers within a production that remained effective on its way out, and looks to have been profitably rehearsed. That said, 36 years is a good long run.

An enjoyable 20-minute bonus feature offers interviews, glimpses of rehearsal, and reminiscences on Mr. Schlesinger, whose cinematic sensibilities and celebrated film career are remarked upon. The three singers of Hoffmann’s love interests (Stella is a speaking actress) are much as their characters are on the stage: Ms. Fomina is bubbly and light, Ms. Yoncheva sensitive and poised, Ms. Rice earthy and wry, with one of those wonderful low, purring Englishwoman voices that would be great for broadcasting. The production’s original movement director, Eleanor Fazan, 86 in 2016, returned for this revival.

Nicklausse’s “C’est l’amour vainqueur,” for example, becomes an entr’acte between “Olympia” and “Antonia.” The partition between “Giulietta” and the epilogue is blown through, with the final drinking chorus horning in ahead of schedule. The roles of Schlemil and Pitichinaccio are entirely excised. Sung lines are boldly reassigned. Hoffmann, not the Muse, takes the lead in the apotheosis. References to Elias the Jew are rewritten (“Offenbach the Jew”).

The production begins with “Stella,” an inebriated drag queen played by actor/stuntman Pär (Pelle) Karlsson in silver dress, blond wig and blue eye-shadow, tumbling halfway down the staircase of a Busby Berkeley-style production number. Stella attempts to sing along with the Spirits of Wine and Beer (male and female choristers in gender-bending costumes) and can only manage strangled cries. Stella, like Frantz to come, longs to sing and dance but can do neither.

The identically dressed and wigged Muse, the first of many doubles, then appears atop the staircase. Although ostensibly female, she has a dangling (false) penis. A heckler shouts homophobic abuse about this not being what the composer intended. This bourgeois supporter of art, who supports art only on his own terms, is drawn from the audience into the staging as Lindorf, subsequent villains, and a fifth role, beleaguered barkeep Luther.

The tenor in the Andrès/Cochenille/Frantz roles is made to resemble Offenbach. (Composers have been turning up in their own operas a lot lately. Mr. Herheim did better a year later with Tchaikovsky in Pikovaya Dama.) Offenbach at times controls the action by waving a quill. Another character may snatch the quill away and take control of the show.

Hoffmann is given exaggerations of the real E.T.A. Hoffmann’s physical characteristics, and Nicklausse and the chorus make up a platoon of Hoffmann clones. The same costumes return over and over, on men and women alike, blurring lines of identity and gender: Stella’s silver dress and blond wig, Hoffmann’s black suit, and a “drag queen in transition” costume (bustier, garters, wig cap),

There is a suggestion that the failures of Hoffmann’s loves are projections of his own failings: vapidity, excessive ambition, faithlessness. At times in “Olympia,” Hoffmann himself moves like an automaton, and the act ends with the destruction of a life-sized Hoffmann doll. In the following act, in one of the production’s wittiest meta touches, Frantz/”Offenbach” sings “Jour et nuit” while trying to put “Hoffmann” together.

He can make the pieces fit, but then they fall apart, as the opera often has. The role of Giulietta is split between the Olympia and Antonia sopranos, and “L’amor lui dit: la belle” is a three-woman relay aria, with the Muse joining in. The three, identically dressed, surround Hoffmann and alternate lines.

Mr. Herheim shows here, as usual, his ability to unite and blend singers into an effective theatrical ensemble. There is hardly a musical movement in the production that is not loaded with meaning, sometimes clear, sometimes inscrutable or open to interpretation. There is a lot to smile at, for example, a four-person dance number (Nicklausse, Cochenille/Offenbach, Hoffmann, Coppelius) during the “eyes” trio.

But over a long three hours, this deliberate embrace of Hoffmann as something fragmented and incomplete, with ideas standing in for characters, “commentary” prioritized over narrative, adds up to less than the sum of its parts. The production never settles down long enough to qualify as a meditation on any of what it touches upon–fluidity of gender; lovers as other sides of ourselves; differing expectations of art on the part of creators, interpreters and audience members .

One does not have to be this production’s Lindorf—who periodically returns to his orchestra seat to complain, discuss the plot with Nicklausse, or doze off—to come away feeling this is less a puzzle than a few puzzles, no one complete. Although it hangs together better on repeated viewing, it never rises to the level of the director’s best work, including his similarly dislocating Rusalka. Christof Hetzer‘s functional but uninspired set work does not help. As some reviewers noted at the time, this is low on the eye-candy level for a Herheim production.

At his best Mr. Herheim questions and tantalizes, but there is an inviting quality to his productions. Rather than yielding, it seems to me, this one hardens. Having hardened, it thrusts without ever penetrating. The apotheosis is sung directly to the audience, with the house lights up, and this has a consoling quality—an inspired and emotionally generous conclusion that does not feel earned.

The musical performance is not distinguished. Christophe Mortagne (Spalanzani in the ROH performance) deftly handles the Offenbach/lackey characters, and Ketil Hugaas is an excellent standard Crespel. Mandy Fredrich, singing all of Antonia and half of Giulietta, has the production’s most beautiful, colorful and evenly produced voice, and may have a one-woman Hoffmann production in her (she is also a Queen of the Night). She is the one woman here I would go out of my way to hear in something else, on this evidence alone.

The good news ends there. Rachel Frenkel is a vocally slender Muse/Nicklausse and voice of Antonia’s mother, satisfactory but not more than that. Kerstin Avemo sings Olympia and the other half of Giulietta. “Les oiseaux dans la charmille” is a mess—shrill and beset by problems of balance and breathing—but Ms. Avemo must sing Olympia’s party piece while acting performance anxiety, rivalry with a jealous Nicklausse, and rough sex with Hoffmann, first as object and then as aggressor.

Michael Volle was in difficult waters vocally at the time, and the video release does not conceal this. Lindorf, Luther, Coppelius, Miracle and Dapertutto benefit from his customary strong presence and intelligence, and he is up for baring his butt as Luther and performing Miracle in bustier and garters. He is commanding in recitative, but it is a rough-sounding performance, fatigued and worrisome by the time “Scintille, diamant” comes around.

You root for this Dapertutto to make it through, and he does…just. Daniel Johansson‘s brawny tenor makes a promising initial impression in Hoffmann’s music, but there is not much variety in color or dynamics, and Mr. Johansson too has audibly tired by the time the show gets to Venice.

Johannes Debus, leading the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, elicits a more propulsive, driven account of the score than his London counterpart does, but again, for the dash and suavity that seem to me integral to this music…well, never mind me. I will be over here with my old Pierre Monteux recording.

I cannot strongly recommend either of these performances as the best Contes d’Hoffmann available on video, but in this showdown of “traditional” (London) versus Regietheater (Bregenz), traditional comes out the better product. This was not the outcome I had expected, which serves as a reminder that while something may be more or less intriguing as proposed, the tales have to be told.

Comments